4

Chapter Outline

- Evaluating sources (18 minute read)

- Annotating sources (15 minute read)

- Critical information literacy (14 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to school discipline, mental health, gender-based discrimination, police shootings, ableism, autism and anti-vaccination conspiracy theories, children’s mental health, child abuse, poverty, substance use disorders and parenting/pregnancy, tobacco use, neocolonialism and Western hegemony, and COVID-19.

4.1 Evaluating sources

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Use skimming to identify which articles are most relevant to your topic

- Overcome paywalls that block access to scholarly information

- Assess the reputability of resources by looking for bias and rigor

- Apply the SIFT method to evaluate sources of information

- Identify why review articles are helpful to read at the beginning of a project

- Revise their working question and overall project based on knowledge they learn from the scholarly literature

In the previous section, we discussed how to formulate search queries to get the most relevant results. At this point, you should not be staring at a Google Scholar window with 1,000,000 search results. If you haven’t played around in multiple databases and refined your queries using the suggestions in section 3.2, pause here and spend some time working on your search queries. Hopefully, you can find at least a few different queries that provide relevant resources to help you answer your working question or introduce new ideas that might revise or update your working question. Remember that your working question should be revised and updated as you learn more about your topic by searching in the literature.

Skim abstracts

Almost all databases will give you access to an article’s abstract. The abstract is a summary of the main points of an article. It will provide the purpose of the article and summarize the author’s conclusions. Once you have a few good search queries, start skimming through abstracts and find the articles that are most relevant to your working question. Soon enough, you will find articles that are so relevant that you may decide to read the full text.

It is a good idea to cast a wide net at this point, since your project is just beginning. If you like the article, make sure to download the full text PDF to your computer so you can read it later. Save it in a new folder using a descriptive title. I like to include the key message in the title when iI save a file (for example, I saved this article to my computer as Motivation and rewards, praise and punishment). Another model might be to save the first author’s last name, year, and the first few words of the title–find what works best for you.

What do you do with all of those PDFs? As you’ll recall from the previous chapter, I usually keep mine in folders on my cloud storage drive, arranged by topic. For those who are more ambitious, you may want to use a reference manager like Mendeley or Zotero, which can help keep your sources and notes organized. Both of them can also help you build a proper bibliography and organize your notes on each article. At the very least, write some notes on paper or in a word processor reflecting on the articles you skim and how they might be of use in your study.

Getting through paywalls to the article

When students try to download the full text of an article, they will often hit an obstacle: the paywall. A paywall is when a publisher charges you to access a publication. Academic journal articles are expensive, but good news! Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes toward paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. You should be able to access the full text for most of the journal articles you need using your library’s website. Do not limit your literature search to the free articles or random PDFs you find on the internet!

Because journal publishers charge a lot of money for access to journals, your school likely does not pay for all the journals in the world. If your university does not already pay for access to the article, you still do not have to pay for it! You will need to use the interlibrary loan feature on your library’s website. It is often listed under Services. Just enter the information for your article (e.g. author, publication year, title, DOI), and a librarian will get you the PDF of the article that you need from a school that does pay for access to that article.

After you no longer have a university library login, getting a PDF of a journal article becomes more challenging. You can subscribe to journals yourself, and many practitioners do that. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article. They will usually send it to you. Some journal articles are available completely for free. If you followed the links in section 3.1 to examples of different types of articles, many of these pointed to articles that were free to access, as the authors of this text cannot be sure that all readers of this textbook will have access to paywalled articles. Open access journal articles do not have a paywall so are open to the public, but less than 13% of journal articles are open access (Chimmer, Geschuhn, & Vogler, 2015).[1]

Another alternative way to access journal articles is to search in for-profit repositories like Social Science Research Network, Academia.edu, and ResearchGate. You will likely encounter results from these websites if you search for articles in a search engine like Google or Bing, as well as on Google Scholar. Sometimes, these websites require users to create an account in order to view content, and students should consider using a throwaway email to do so. ResearchGate has been sued by scholarly publishers for illegally hosting copyrighted and paywalled content (Mackenzie, 2018).[2] By contrast, non-profit and community-owned repositories like SocArXiv and university repositories (like Virginia Commonwealth University’s Scholars Compass) allow authors to legally share a final draft of their work either prior to publication or after publication within the boundaries set out by publishers. SFU does this through the Summit repository. This practice is called self-archiving or green open access—as contrasted with gold open access, in which the publisher’s version of the journal article is freely available rather than just the author’s draft. Self-archived papers look a lot like the papers you turn in for class. They are formatted according to the style guide predominant in the discipline and intended to be reviewed by experts as part of peer review.

We will address the social equity implications of paywalls and open access at the end of this chapter when we talk about information privilege. For now, we will pass along this advice adapted from the brilliant librarians at Virginia Tech (go Hokies!) on getting through paywalls. While you are in school, your library will likely pay for access to some of the articles you want. Search your library’s collection, and if it does not have access to it right away, request it via inter-library loan, and a copy will come within a few days thanks to some dedicated librarians at your school. If you need the article right away or are not affiliated with a university library, the steps below might be helpful in finding your article.

- Check Google Scholar for alternative versions of the article you are trying to access. On the bottom right of each source in Google Scholar results is a link that says “all # versions.” If the author has uploaded an open access version of their work, you may need to click this link to get to a free copy rather than the paywalled copy at the journal.

- Conduct a search for the article in a normal Google search (possibly adding “.pdf” to the query) to see if you can find a copy of the article without a paywall. Often times, you will find links to a paywalled journal article on a for-profit repository like Acacdemia.edu or ResearchGate. These are okay to download from, but make sure to keep a keen eye on suspicious websites that promise access to journal articles but actually try to infect your computer with malware. If your browser gives you a warning when you go to a page or when you try to download a PDF, don’t risk it. Find another way to get the article.

- Go to unpaywall.org and install the Unpaywall extension for Firefox and Chrome. Once installed, a green icon of an open lock will appear on any scholarly resource for which there is a publicly accessible version without a paywall.

- Go to openaccessbutton.org and either install the Chrome extension or use the web portal to request that the author of an article send you a free copy. The purpose of this project is to make seeking free copies of scholarship as easy as possible, though it still relies on the author to send their article when you request it using this service.

- Go to oahelper.org and install their desktop or mobile app to search for unpaywalled and open access versions of publications.

Everyone can access the abstracts of research articles for free, as long as they have an internet connection. Abstracts are a great place to start, but you need to access the full text of articles for your student projects. I’ve often seen student papers where they do a simple Google Scholar search and only read articles for which there is free access, with the PDF link in the search results. This is a mistake because few journal articles are free to access (Chimmer, Geschuhn, & Vogler, 2015).[3] Use your library to gain access to the full text of each journal article you need for your search. While you are studying at your university, your login is the key to unlock the paywall and grant you access to the information you need.

Which articles do I download?

Keeping your working question in mind, you should look at your potential sources and evaluate whether they are relevant to your inquiry. To assess the relevance of a source, ask yourself if the source will help you answer or think more deeply about your working question. Does the information help you answer this question, challenge your assumptions, or connect your question with another topic? Does the information present an opposing point of view, so you can show that you have addressed all sides of the argument in your paper? Does the article just provide a broad overview of your topic or does it have a specific focus on what you want to study? If the article isn’t helpful to you, it’s okay not to read it. No matter how good your searching skills, some articles won’t be relevant. You don’t need to read and include everything you find!

You may also want to check the relevance of the source with your professor or course syllabus. In my class, I have specific questions I will ask students to address in their literature reviews. You may want to find sources that help you answer the questions in your professor’s prompt for a literature review. For example, my rubric asks students to:

1. Identify the broader topic area

2. Review at least 14 studies

3. Identify themes found in the research

4. Identify points of conflict in the research, as appropriate

5. Identify points of agreement in the research, as appropriate

6. Identify gaps in the research or relates back to the research question

In addition to relevance, you should ask yourself about the quality of the source you’ve found. Is the information outdated? Is the source more than 10 years old? If so, it will not necessarily provide what we currently know about the topic–just what we used to know. Older sources are helpful for historical information, such as how our understanding of a topic has changed over time or how the prevalence of an issue has increase or decreased. Older articles are also important to examine to find out what we already know about the topic–once researchers are comfortable with the state of knowledge in an area, they are likely to move on to new aspects of the issue, so it’s important to at least start with a wider timeframe. However, unless historical analysis is the focus of your literature review, once you have a good understanding of the history of the issue, move on to sources that are more current. Doing so will also narrow down your list of results considerably in a database.

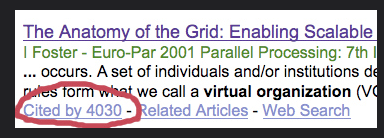

Older sources may be of some importance, however, if they are seminal articles. As we learned in section 3.1, seminal articles are cited often in the literature. They are clearly important to a lot of scholars in the field. While not all articles are seminal, you can get a quick sense of how important an article is to the broader literature on a topic by looking at how many other sources cited it. If you search for the article on Google Scholar (see Figure 3.1 for an example of a search result from Google Scholar), you can see how many other sources cited this information. Generally, the higher the number of citations, the more important the article (or at least, the more widely read). Of course, articles that were recently published will have fewer citations than older articles, and the citation count is only one indicator of an article’s importance.

What evidence is in each type of article?

Literature searching is about finding evidence to inform your ideas, supporting or refuting what you think about a topic. Each type of article (we reviewed some of them in section 3.1) provides different kinds of evidence.

Causal and Inferential Research

As we talked about in section 3.2, a good place to start your literature search is with review articles—meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, and systematic reviews. These types of articles give you a birds-eye view of the literature in a topic area, and with meta-analyses and meta-syntheses, conduct empirical analyses on enormous datasets comprised of the raw data from multiple studies. As a result, their conclusions represent what is broadly true about the topic area. They also have comprehensive reference lists that you can browse for sources relevant to your topic. Finally, they tend to focus on resolving conflicts in the field, so you are likely to get a broad overview of the field and its tensions in the introductory parts of the reviews.

In my experience, students are often tempted to read short articles because they can complete assignments more quickly that way. This is a trap for students starting a literature review. Short articles take less time to read, sure. But this isn’t about reading a certain number of articles, but finding the information you need to write your literature review as accurately and efficiently as possible. You’ll save time by reading more relevant articles with lengthier and more comprehensive literature reviews—in particular, review articles.

Review articles are the best place to start for any literature search, but you should also look for specific types of articles based on your working question. If your working question asks about an intervention, like a teaching technique or program, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the strongest evidence if a meta-analysis or systematic review of relevant RCTs is unavailable. Quasi-experimental designs are considered less powerful because researchers have less control over the research process. You will want to avoid relying heavily on articles that use non-experimental designs and include words like “pilot study,” “convenience sample,” or “exploratory study” in their methods section. These are preliminary studies that are done prior to a more rigorous experiment like an RCT, and their conclusions are tentative and collected for the purpose of informing future inquiry, not establishing what is true for broader populations. We will discuss experimental design in Chapter 13, but for now, it’s important to know that the purpose is often to establish the efficacy of an intervention and the truth value of the evidence contained in them varies based on the design of the experiment, with RCTs being the “gold standard.”

Experiments are one of two quantitative designs explored in this book. The other design is survey research. Looking at survey research is a good idea in any project, as it provides evidence about broader populations by generalizing from a smaller sample of people. For example, surveys can tell you about the risk and protective factors for a social problem by querying the people who are likely to experience that problem over time. Longitudinal surveys are often the most helpful in understanding causality because you have a record of how things have changed over time. Cross-sectional surveys are more limited in establishing causal relationships, as they only query people at one point in time. We discuss the differences between these types of surveys in Chapter 12. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys are very commonly cited types of sources in education literature reviews because their results are often applicable across broad populations. However, they are limited in the degree to which they can establish causality, as they lack the controlled environment of an experiment. As with experiments, students should be very cautious about using survey results that are “exploratory” or a “pilot study,” as the purpose of those studies is to inform future research rather than understand what is true about broader populations.

The previous few paragraphs can be summarized in this hierarchy of evidence, as described by McNeese & Thyer (2004).[4] The higher a type of article on this list, the better they can reliably and directly inform evidence-based practice.

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Randomized controlled trials

- Quasi-experimental studies

- Case-control and cohort studies

- Pre-experimental (or non-experimental) group studies

- Surveys

- Qualitative studies

Descriptive and Qualitative Research

The hierarchy of evidence is a useful heuristic, and it is based on sound reasoning. A systematic review or meta-analysis will provide you with a better picture of what is generally true for most people about a given topic than a qualitative study. However, generalizable objective truth is not the only thing researchers want to know (and theorists like W. Graham Astley[5] would argue whether there is such a thing as an “objective truth“). Moving on from that ontological debate, if you wanted to research the impact of violence on a school community, systematic reviews would not provide you the depth you need to understand the stories of people impacted. That’s not what systematic reviews are designed to do.

To find evidence like that, the most relevant evidence is in qualitative studies, at the “bottom” of the hierarchy. For this reason, it is better to think of the hierarchy of evidence within the broader context of your working question and the knowledge you need to investigate it. Different types of sources are useful depending on what your question is (and the outcome you want). Table 4.1 contains a suggested starting point for evaluating what types of literature will provide the most relevant evidence for your project.

| What you want know about: | The most relevant evidence will be found in a: |

| General knowledge about a topic | Systematic review, meta-analysis literature review, textbook, encyclopedia |

| Intervention (treatment, policy, program) | Randomized controlled trial (RCT), meta-analysis, systematic review, cohort study, case-control study, case series, clinical practice guidelines |

| Lived experience & sociocultural context | Qualitative study, participatory and action research, humanities and cultural studies |

| Theory and practice models | Theoretical and non-empirical article, textbook, manual for an evidence-based treatment, book or edited volume |

| Prevalence of a diagnosis or social problem | Survey research, government and nonprofit reports |

| How practitioners think about a topic | Practice note, survey or qualitative study of practitioners, reports from professional organizations |

Qualitative studies are not designed to provide information about a broader population. As a result, you should treat their results as related to the specific time and place in which they occurred. If a study’s context is similar to the one you plan to research, then you might expect similar results to emerge in your research project. Qualitative studies provide the lived experience and personal reflections of people knowledgeable about your topic. These subjective truths provide evidence that is just as important as other studies in the hierarchy of evidence.

Sources other than journal articles

We’ve focused mostly on evaluating academic journal articles thus far. While you can be assured that articles in reputable journals have passed peer review, that does not always mean they contain accurate information. Articles are often debated on social media or in journalistic outlets. For example, here is a news story debunking a journal article which erroneously found Safe Consumption Sites for people who use drugs were moderately associated with crime increases. After multiple scholars evaluated the article’s data, they realized there were flaws in the design and the conclusions were not supported, which led the journal to retract the article. You can find these controversies in the literature by using a Google Scholar feature we’ve talked about before—’Cited By’. Click the ‘Cited By’ link to see which articles cited the article you are evaluating. If you see critical commentary on the article by other scholars, it is likely an area of active scientific debate. You should investigate the controversy further prior to making any conclusive claims in your literature review.

If your literature search contains sources other than academic journal articles (and almost all of them do), you’ll need to do a bit more work to assess whether the source is reputable enough to include in your review. Let’s say you find a report from a Google Scholar search or a Bing search. Without peer review or a journal’s approval, how do you know the information you are reading is any good?

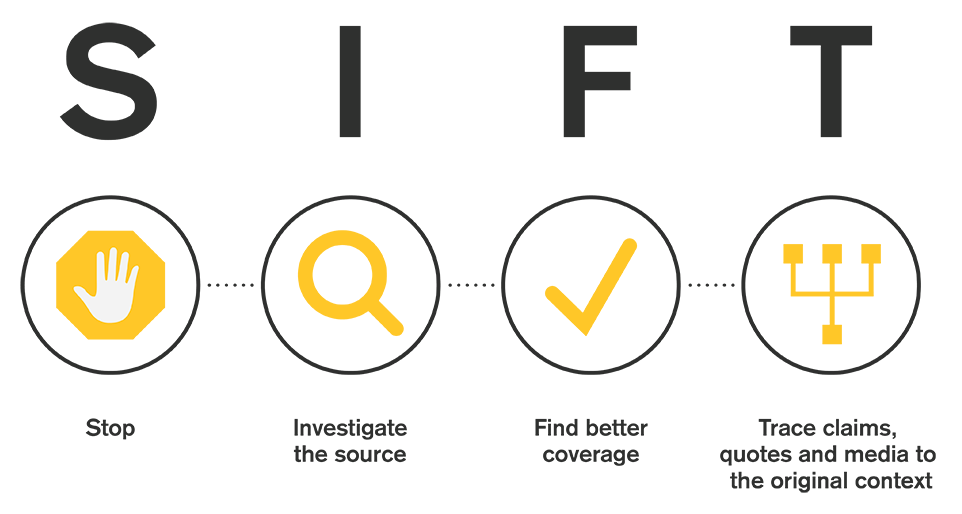

The SIFT method

Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention. It is referred to as the “SIFT” method, and it stands for Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context.

Stop

Stop

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging! What about this website is driving your engagement (positively or negatively)?

Investigate the sources

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source to determine its truth. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of privatized education services, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by a conservative think tank like the Fraser Institute. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the Fraser Institute can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. Indeed, one study cited in the video below found that academic historians are actually less able to tell the difference between reputable and bogus internet sources because they do not read laterally but instead check references and credentials. Those are certainly a good idea to check when reading a source in detail, but fact checkers instead ask what other sources on the web say about it rather than what the source says about itself. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating. Not only is this faster, but it harnesses the collected knowledge of the web to more accurately determine whether a source is reputable or not.

We recommend watching this short video [2:44] for a demonstration of how to investigate online sources. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors. Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find better coverage

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source. The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there.

We recommend watching this short video [4:10] that demonstrates how to find better coverage and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage. Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. We talked about this in Chapter 3 when we distinguished between primary sources and secondary sources. Secondary and tertiary sources are great for getting started with a topic, but researchers want to rely on the most highly informed source to give us information about a topic. If you see a news article about a research study, look for the journal article written by the researchers who performed the study as citations for your paper rather than a journalist who is unaffiliated with the project.

We recommend watching this short video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source. Researchers must follow the thread of information from where they first read it to where it originated in order to understand its truth and value. Social workers who fail to check their sources can spread misinformation within our practice context or come to ill-informed conclusions that hurt clients or communities.

Once you have limited your search to trustworthy sources, ask yourself the following questions when evaluating which of these sources to download:

- Does this source help me answer my working question?

- Does this source help me revise and focus my working question?

- Does this source help me address what my professor expects in a literature review?

- Is this the best source I can find? Is this a primary or secondary source?

- What is the original context of this information?

- Is there controversy surrounding this source?

- Are the publisher and author reputable and unbiased?

Reflect and plan for the future

As you look through abstracts and search the literature, you will learn more about your topic area. You will learn new concepts that become new keywords in new queries. You will continue to come up with search queries and download articles throughout the research process. While we present this material at the beginning of the textbook, that is a bit misleading. You will return to search the literature often during the research process. As such, it is important to keep notes about what you did at each stage. I usually keep a “working notes” document in the same folder as the PDFs of articles I download. I can write down which categories different articles fall into (e.g., theoretical articles, empirical articles), reflect on how my question may need to change, or highlight important unresolved questions or gaps revealed in my search.

Creating and refining your working question will help you identify the key concepts you study will address. Once you identify those concepts, you’ll need to decide how to define them and how to measure them when it comes time to collect your data. As you are reading articles, note how other researchers who study your topic define concepts theoretically in the introduction and measure them in their methods section. Tuck these notes away for the future, when you will have to define and measure these concepts.

You also need to think about who your research participants will be and what larger group(s) they may represent. You need to be able to speak intelligently about the target population you want to study, so finding literature about their strengths, challenges, and how they have been impacted by historical and cultural oppression is a good idea. Last, but certainly not least, you should consider any potential ethical concerns that could arise during the course of carrying out your research project. These concerns might come up during your data collection, but they may also arise when you get to the point of analyzing data or disseminating results.

Decisions about the various research components do not necessarily occur in sequential order. For example, you may have to think about potential ethical concerns before changing your working question. In summary, the following list shows some of the major components you’ll need to consider as you design your research project. Make sure you have information that will inform how you think about each component.

- Research question

- Literature review

- Theories and causal relationships

- Unit of analysis and unit of observation

- Key concepts (conceptual definitions and operational definitions)

- Method of data collection

- Research participants (sample and population)

- Ethical concerns

Carve some time out each week during the beginning of the research process to revisit your working question. As you write notes on the articles you find, reflect on how that knowledge would impact your working question and the purpose of your research. You still have some time to figure it out. We’ll work on turning your working question into a full-fledged research question in Chapter 9.

Key Takeaways

- Once you have a reasonable number of search results, you can start skimming abstracts. If an article is relevant to your project, download the full text PDF to a folder on your computer.

- Download strategically, based on what your professor expects in your literature review and what information you need to understand, revise, and answer your working question.

- Paywalls do not apply to students at a university. You have access to a lot of articles through your university’s library or through interlibrary loan. Do not limit yourself to PDFs floating around on the internet.

- Write notes to yourself, so you can track how your project has developed over time.

Exercises

- Using your search queries from section 3.2, skim abstracts and download articles that are likely to be relevant to your research project. Create a folder on your hard drive to store the PDFs.

- Look at your professor’s prompt for a literature review and sketch out how you might answer those questions using your present level of knowledge. Search for sources that support or challenge what you think is true about your topic.

- Pull out five important points related to your topic that you have taken away from your search thus far and discuss them with a peer. This will begin to acclimate you to synthesizing and discussing the literature in your area.

4.2 Annotating sources

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define annotation and describe how to use it to identify, extract, and reflect on the information you need from an article

After working through the exercises Chapter 3, you should have a folder full of articles. For me, searching the literature is the fun part of a literature review. I have grand ideas about reading this article and that article and every article! Once I’m satisfied I have enough literature to speak intelligently on my topic, a creeping sense of dread kicks in. How will I ever find the time to read 60 journal articles?! This chapter is all about how to pick the most relevant articles, write notes about them, and incorporate the information relevant to your working question in your literature review.

Read literature reviews

At the beginning of a research project, you don’t know a lot about your research topic. You don’t even know what you don’t know! That’s why it’s a good idea to get a broad, birds-eye view of the literature by looking at other literature reviews. Someone has gone through the trouble of reading a few dozen sources and telling you what’s important about them. Get a broad sense of the literature and follow up on subtopics that interest you. As we discussed in Chapter 3, review articles are useful because they synthesize all the information on a given topic. By reading what another researcher thinks about the literature, you can get a more wide-ranging sense of it than reading the results of only one study.

As we discussed in the last chapter, review articles will often have “literature review,” “systematic review,” or other similar terms in the title. These articles are 100% literature review. The author’s primary goal is to present a comprehensive and authoritative view of the important research in a particular topic area. Think of these as a way to engage with dozens of articles at the same time, and you can find a lot of relevant references from reading the article. For the same reason, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses are also excellent sources as you are starting a literature review.

Unfortunately, review articles do not exist for every topic. If you are unable to find a review article, try to find an empirical article that has a lengthy literature review. You are mostly reading to see what the author says about the literature on your topic in the introduction and discussion sections. In this way, you can use the author’s literature search to inform your own. You will likely find new ideas and get a sense of the broader scientific literature just by reading what other researchers think about the literature.

Annotation

Annotation refers to the process of writing notes on an article. There are many ways to do this. The most basic technique is to print out the article and build a binder related to your topic. Raul Pacheco-Vega’s excellent blog has a post on his approach to taking physical notes. Honestly, while you are there, browse around that website. It is full of amazing tips for students conducting a literature review and graduate research projects. I see a lot of benefits to the paper, pen, and highlighter approach to annotating articles. Personally though, I prefer to use a computer to write notes on an article because my handwriting is terrible and typing notes allows me search for keywords. For other students, electronic notes work best because they cannot afford to print every article that they will use in their paper. No matter what you use, the point is that you need to write notes when you’re reading. Reading is research!

There are a number of free software tools you can use to help you annotate a journal article. Most PDF readers like Adobe Acrobat have a commenting and highlighting feature, though the PDF readers included with internet browsers like Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, and Safari do not have this feature and searching notes taken in this manner is cumbersome. The best approach may be to use a citation manager like Mendeley or its open-source alternative, Zotero. Again, Raul Pacheco-Vega’s guide to using Mendeley is stellar. Using citation managers, you can build a library of articles, save your annotations, and link annotations across PDFs using keywords. They also provide integration with word processing programs to help with citations in a reference list.

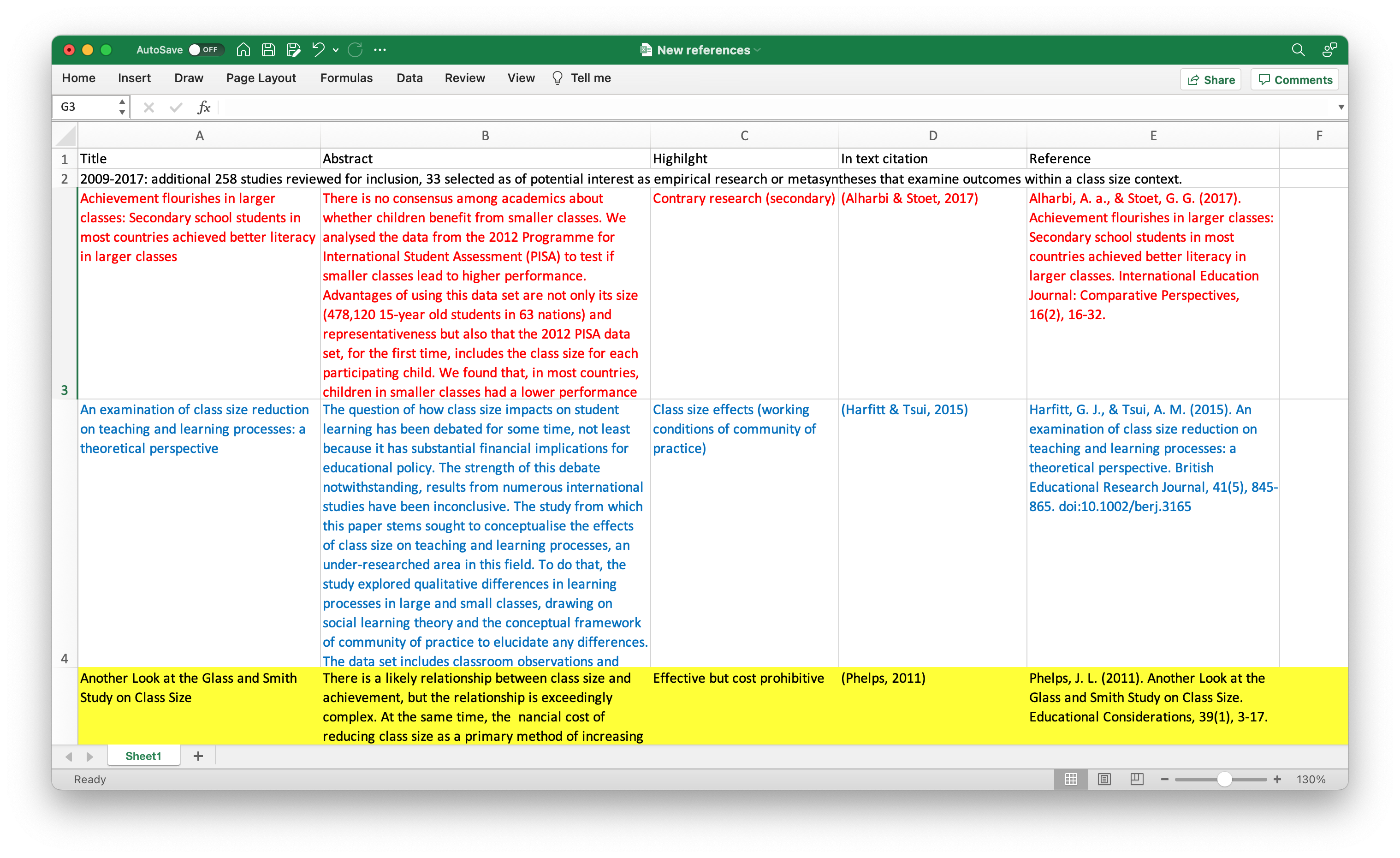

Of course, I don’t follow this advice because I have a system that works well for me. I have a PDF open in one computer window and an Excel file in a window next to it. I type in the the title, abstract, highilghts, the in-text citation, an the APA reference for easy incorporation into a paper. It’s a bit low-tech, but it does make my notes searchable and helps me find the full study quickly as needed. This way, when I am looking for a concept or quote, I can simply search my notes using the Find feature and get to the information I need. I also break the research into separate category “sheets” within my spread sheet (or color code themes) as I see themes develop. See image below as an example.

Annotation and reviewing literature does not have to be a solo project. If are working in a group, you can use the Hypothes.is web browser extension to annotate articles collaboratively. You can also use Google Docs to collaboratively annotate a PDF using the commenting feature and write collaborative notes in a shared document. By sharing your highlights and comments, you can split the work of getting the most out of each article you read and build off one another’s ideas.

The most important point here is to create a system to organize the research that works for you and to stick to it. There’s nothing worse than having a bunch of studies that you can’t remember your reason for downloading, or to have a great quote in your paper that you can’t find the reference for. The next section deals with ways you might organize the research you find during your literature search.

Common annotations

In this section, we present common annotations people make when reading journal articles. These annotations are adapted from Craig Whippo and Raul Pacheco-Vega. If you are annotating on paper, I suggest using different color highlighters for each type of annotation listed below. If you are annotating electronically, you can use the names below as tags to easily find information later. For example, if you are searching for definitions of key concepts, you can either click on the tag for [definitions] in your PDF reader or thumb through a printed copy of article for whatever color or tag you used to indicate definitions of key terms. Most of all, you want to avoid reading through all of your sources again just to find that one thing you know you read somewhere. Time is a graduate student’s most valuable resource, so our goal here is to help you spend your time reading the literature wisely.

Personal reflections

Personal reflections are all about you. What do you think? Are there any areas you are confused about? Any new ideas or reflections come to mind while you’re reading? Treat these annotations as a means of capturing your first reflections about an article. Write down any questions or thoughts that come to mind as you read. If you think the author says something inaccurate or unsubstantiated, write that down. If you don’t understand something, make a note about it and ask your professor. Don’t feel bad! Journal articles are hard to understand sometimes, even for professors. Your goal is to critically read the literature, so write down what you think while reading! Table 4.2 contains some questions that might stimulate your thoughts.

| Report section | Questions worth asking |

| Abstract | What are the key findings? How were those findings reached? How does the author frame their study? |

| Acknowledgments | Who are this study’s major stakeholders? Who provided feedback? Who provided support in the form of funding or other resources? |

| Problem statement (introduction) | How does the author frame the research focus? What other possible ways of framing the problem exist? Why might the author have chosen this particular way of framing the problem? |

| Literature review (introduction) |

What are the major themes the author identifies in the literature? Are there any gaps in the literature? Does the author address challenges or limitations to the studies they cite? Is there enough literature to frame the rest of the article or do you have unanswered questions? Does the author provide conceptual definitions for important ideas or use a theoretical perspective to inform their analysis? |

| Sample (methods) | Where was the data collected? Did the researchers provide enough information about the sample and sampling process for you to assess its quality? Did the researchers collect their own data or use someone else’s data? What population is the study trying to make claims about, and does the sample represent that population well? What are the sample’s major strengths and major weaknesses? |

| Data collection (methods) | How were the data collected? What do you know about the relative strengths and weaknesses of the methods employed? What other methods of data collection might have been employed, and why was this particular method employed? What do you know about the data collection strategy and instruments (e.g., questions asked, locations observed)? What don’t you know about the data collection strategy and instruments? Look for appendixes and supplementary documents that provide details on measures. |

| Data analysis (methods) | How were the data analyzed? Is there enough information provided for you to feel confident that the proper analytic procedures were employed accurately? How open are the data? Can you access the data in an open repository? Did the researchers register their hypotheses and methods prior to data collection? Is there a data disclosure statement available? |

| Results | What are the study’s major findings? Are findings linked back to previously described research questions, objectives, hypotheses, and literature? Are sufficient amounts of data (e.g., quotes and observations in qualitative work, statistics in quantitative work) provided to support conclusions? Are tables readable? |

| Discussion/conclusion | Does the author generalize to some population beyond the sample? How are these claims presented? Are claims supported by data provided in the results section (e.g., supporting quotes, statistical significance)? Have limitations of the study been fully disclosed and adequately addressed? Are implications sufficiently explored? |

Definitions

Note definitions of key terms for your topic. At minimum, you should include a scholarly definition for the concepts represented in your working question. If your working question asks about the the effect of assessment on student achievement, your research proposal will have to explain how you define assessment, as well as how you define achievement. While you may already know what you mean by assessment, the person reading your research proposal does not.

Annotating definitions also helps you engage with the scholarly debate around your topic. Definitions are often contested among scholars. Some definitions of achievement will be more comprehensive, including things such as test scores, but also grades, graduation rates or employment. Other definitions will be less comprehensive, covering only standardized test scores, for example. Assessment can be formative or summative; criterion or norm referenced; or diagnostic, placement or screening. Assessment is also frequently conflated with testing (measuring discrete knowledge or skills) or evaluation (making a judgement based on collected evidence) while it’s formal definition is as a process by which attributes of phenomena (learning) are described. Often, how someone defines something conceptually is highly related to how they measure it in their study. Since you will have to do both of these things, find a definition that feels right to you or create your own, noting the ways in which it is similar or different from those in the literature.

Definitions are also an important way of dealing with jargon. Becoming familiar with a new content area involves learning the jargon experts use. For example, in the last paragraph I used the term criterion referenced, but that may not be a term you’ve heard before. If you were conducting a literature review on assessment, you would want to search for keywords like criterion and norm referenced , or differentiate assessment from testing and evaluation as relevant to your working question. You will also want to know what they mean so you can use them appropriately in designing your study and writing your literature review.

Theoretical perspective

Noting the theoretical perspective of the article can help you interpret the data in the same manner as the author. For example, articles on student learning may stem from Cognitive, Behaviourist, or Constructivist theory, and understanding which theory is being used is important to make sense of empirical results. Articles should be grounded in a theoretical perspective that helps the author conceptualize and understand the data. As we discussed in Chapter 3, some journal articles are entirely theoretical and help you understand the theories or conceptual models related to your topic. We will help you determine a theoretical perspective for your project in Chapter 7. For now, it’s a good idea to note what theories authors mention when talking about your topic area. Some articles are better about this than others, and many authors make it a bit challenging to find theory (if mentioned at all). In other articles, it may help to note which theories are missing from the literature. For example, a study’s findings might address issues of oppression and discrimination, but the authors may not use critical theory to make sense of what happened.

Background knowledge

It’s also a good idea to note any relevant information the author relies on for background. When an author cites facts or opinions from others, you are subsequently able to get information from multiple articles simultaneously. For example, if we were looking at this meta-analysis about domestic violence, in the introduction section, the authors provide facts from many other sources. These facts will likely be relevant to your inquiry on domestic violence, as well.

As you are looking at background information, you should also note any subtopics or concepts about which there is controversy or consensus. The author may present one viewpoint and then an opposing viewpoint, something you may do in your literature review as well. Similarly, they may present facts that scholars in the field have come to consensus on and describe the ways in which different sources support these conclusions.

Sources of interest

Note any relevant sources the author cites. If there is any background information you plan to use, note the original source of that information. When you write your literature review, cite the original source of a piece of information you are using, which may not be where you initially read it. Remember that you should read and refer to the primary source. If you are reading Article A and the author cites a fact from Article B, you should track down Article B and use it when you cite the fact in your paper. You do this to make sure Article A interpreted Article B correctly and scan Article B for any other useful facts.

Research question/Purpose

Authors should be clear about the purpose of their article. Charitable authors will give you a sentence that starts with something like this:

- “The purpose of this research project was…”

- “Our research question was…”

- “The research project was designed to test the following hypothesis…”

Unfortunately, not all authors are so clear, and you may have to hunt around for the research question or hypothesis. Generally, in an empirical article, the research question or hypothesis is at the end of the introduction. In non-empirical articles, the author will likely discuss the purpose of the article in the abstract or introduction.

Results

We will discuss in greater detail how to read the results of empirical articles in Chapter 5. For now, just know that you should highlight any of the key findings of an article. They will be described very briefly in the abstract, and in much more detail in the article itself. In an empirical article, you should look at both the ‘Results’ and ‘Discussion’ sections. For a non-empirical article, the key findings will likely be in the conclusion.

Measures

How do researchers know something when they see it? Found in the ‘Methods’ section of empirical articles, the measures section is where researchers spell out the tools, or measures, they used to gather data. For quantitative studies, you will want to get familiar with the questions researchers typically use to measure key variables. For example, to measure whether children are having difficulty recognizing letter and number orientations researchers may use the Jordan Left-Right Reversal Test. The more frequently used and cited a measure is, the more we know about how well it works (or not). In education you can find out what we know about many standardized commercially available tests through the Mental Measurements Yearbook (including the Jordan Left-Right Reversal Test). Qualitative studies will often provide at least some of the interview or focus group questions they used with research participants. They will also include information about how their inquiry and hypotheses may have evolved over time. Keep in mind however, sometimes important information is cut out of an article during editing. If you need more information, consider reaching out to the author directly. Before you do so, check if the author provided an appendix with the information you need or if the article links to a their data and measures as part open data sharing practices.

Sample

Who exactly were the study participants and how were they recruited? In quantitative studies, you will want to pay attention to the sample size. Generally, the larger the sample, the greater the study’s explanatory power. Additionally, randomly drawn samples are desirable because they leave any variation up to chance. Samples that are conducted out of convenience can be biased and non-representative of the larger population. In qualitative studies, non-random sampling is appropriate but consider this: how well does what we find for this group of people transfer to the people who will be in your study? For qualitative studies and quantitative studies, look for how well the sample is described and whether there are important characteristics missing from the article that you would need to determine the quality of the sample.

Limitations

Honest authors will include these at the end of each article. But you should also note any additional limitations you find with their work as well.

Your annotations

These are just a few suggested annotations, but you can come up with your own. For example, maybe there are annotations you would use for different assignments or for the problem statement in your research proposal. If you have an argument or idea that keeps coming to mind when you read, consider creating an annotation for it so you can remember which part of each article supports your ideas. Whatever works for you. The goal with annotation is to extract as much information from each article while reading, so you don’t have to go back through everything again. It’s useless to read an article and forget most of what you read, or to waste time digging through dozens of studies to find that one critical point you remember reading (but not where you read it). Annotate!

Key Takeaways

- Begin your search by reading thorough and cohesive literature reviews. Review articles are great sources of information to get a broad perspective of your topic.

- Don’t read an article just to say you’ve read it. Annotate and take notes so you don’t have to re-read it later.

- Use software or paper-and-pencil approaches to writing notes on articles.

Exercises

- Select a review article to read. Ideally, this will be literature review, systematic review, or meta-analysis, or if those are not available, an article with a lengthy literature review in the introduction and discussion sections.

- Annotate the article using the aforementioned annotations and create some of your own.

- Write a few sentences reflecting on what you learned and what you want to read about next.

4.3 Critical information literacy

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define critical information literacy

- Explore the relationship between education practice, consuming social science, and fighting for social justice

Ultimately, searching and reviewing the literature will be one of the most transferable skills from your research methods classes. All educators consume research information as part of their jobs. In this closing section, we hope to ground this orientation toward scientific literature in your identity as an educator, scholar, and social scientist. In one sense, to be a critical consumer of research is to be discerning about which sources of information you read and why. If you have followed along with the exercises in this chapter, you hopefully have 30, 50, or even 100 PDFs of articles that are relevant to your project in a folder on your computer. You do not have to read every article or source that discusses your topic.

At some point, reading another article won’t add anything new to your literature review. We’ve discussed in this chapter how to read sources strategically, getting the most out of each one without wasting your time. Ultimately, the number of sources you need should be guided, at a minimum, by your professor’s expectations and what you need to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on your topic. The purpose of the literature review is to give an overview of the research relevant to your project—everything a reader would need to understand the importance, purpose, and thought behind your project—not for you to restate everything that has ever been studied about your topic.

Research is a human right

But when we talk about being critical in education, we mean more than critical thinking. The core skill you are developing in Chapters 3-5 of this textbook is information literacy, or “a set of abilities requiring individuals to ‘recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (American Library Association, 2020).[6] Information literacy is key to the lifelong learning process of education practice, as you will have to continue to absorb new information after you leave school and progress as an educator. In the evidence-based practice process, information literacy is a key component in helping students and schools achieve their goals.

However, education researchers and librarians dedicated to social change embrace a more progressive conceptualization of this skill called critical information literacy. It is not enough to simply know how to use the tools we use to share knowledge. Instead, education researchers should critically examine “the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory & Higgins, 2013, p. ix).[7] Just like all other social structures, those we use to create and share scientific knowledge are subject to the same oppressive forces we encounter in everyday life—racism, sexism, classism, and so forth. Critical information literacy combines both fine-tuned skills for finding and evaluating literature as well as an understanding of the cultural forces of oppression and domination that structure the availability of information. As Tewell (2016)[8] argues, “critical information literacy is an attempt to render visible the complex workings of information so that we may identify and act upon the power structures that shape our lives” (para. 6).

From critical information literacy, we get the term information privilege which is defined by Booth (2017)[9] as:

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access. Individuals with the resources to access the information they need, are affiliated with research or academic institutions and libraries, or live close to a public library with access to resources and services such as free interlibrary loan are examples of those with information privilege. Those who are unable to access the information they need are information underprivileged or impoverished [emphasis in original]; this includes people who are incarcerated, poor, unaffiliated with a university or research institution, or live in rural areas distant from a public library.

How can you recognize information privilege? The video from the Steely Library at Northern Kentucky University below will help you.

It is important to recognize your own information privilege and use it to help enact social change on behalf of those who are oppressed within the system of scholarly knowledge production and sharing we currently have. We previously discussed the issue of paywalls in this chapter. Paywalls lock away access to knowledge to only those who can afford to pay, shutting out those with fewer resources. This effect of publishing primarily in journals that require a paywall is endemic to university scholarship in general, as Robinson-Garcia and colleagues (2020)[10] note, the “median share of publications openly available of universities worldwide is 43%”, with publications from researchers at Canadian institutions falling below even that low figure. The reasons for this are not financial, as authors do not profit from the sales of journal articles. Indeed, faculty who edit, review, and author articles are not paid for their work under the current model of commercial journal publication. Scholars do not have a meaningful share in the 31.3% profit margins of Elsevier, the largest commercial publisher of scholarly journals (RELX, 2019).[11] Libraries are struggling to keep up with annual price increases. This topsy-turvy world is best encapsulated in Figure 4.1, which summarizes the problems in scholarly publication succinctly.

As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, paywalls effectively shut out students from accessing journal articles after they graduate.[12] However, paywalls also shut out community members, students, and advocates from accessing the research information they need to effectively advocate for themselves. This is because paywalls are an obstruction to the basic human right to access and interact with the knowledge humanity creates.

As Willinsky (2006) states, “access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend, as well as to advocate for, other rights.” The open access movement is a human rights movement that seeks to secure the universal right to freely access information in order to produce social change. Information is a resource, and the current approach to sharing that resource—the key to human development—excludes many oppressed groups from accessing what they need to address matters of social justice. Appadurai (2006)[13] conceptualizes this as a “right to research…the right to the tools through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as citizens” (p. 168). From a human rights perspective, research is not something confined to professional researchers but “the capacity to systematically increase the horizons of one’s current knowledge, in relation to some task, goal or aspiration” (p. 173).

In Chapter 2, we discussed action research which includes community members as part of the research team. Action research addresses information privilege by addressing the power imbalance between academic researchers and community members, ensuring that the voice of the community is represented throughout the process of creating scientific knowledge. This equity-enhancing process provides community members with access to scientific knowledge in many ways: (1) access via academic to scholarly databases, (2) access to the training and human capital of the researcher, who embodies years of education in how to conduct social science research, and (3) access to the specialized resources like statistical or qualitative data analysis software required to conduct scientific research. Moreover, it highlights that while open access is important, it is only one half of the equation. Open access only addresses how people receive scholarly information. But what about how social science knowledge is created? Action research underscores that equity is not just about accessing scientific knowledge, but co-creating scientific knowledge as partners with community members. Critical information literacy critiques the current practices of scientific inquiry in education and other disciplines as exclusionary, as they reinforce existing sources of privilege and oppression.

This imbalance between academic researchers and community members should be considered within an English-speaking, Western context. The widespread adoption of open access and open science in the developing world underscores the extreme imbalances that international researchers face in accessing scholarly information (Arunachalam, 2017).[14] Paywalls, barriers to international travel, and the tradition of in-person physical conferences structure the information sharing practices in social science in a manner that excludes participation from researchers who lack the financial and practical resources to access these exclusionary spaces (Bali & Caines, 2016; Eaves, 2020).[15]

In the Canada, the federal government has increasingly adopted policies that facilitate open access, including the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) requirement that all publications from projects they fund must be open access within a year after publication in a commercial journal. The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) has been working with the U.S. presidential administrations on a formal proposal to make all research articles published using federal grant funds accessible to the public as open access, though at the time of this writing there was no final agreement on the policy design or implementation. In Europe, Plan S is a multi-stakeholder social change coalition that is seeking structural change to scholarly publication and open access to research. Latin America and South America are far ahead of their Western counterparts in adopting open access, providing a view of what is possible when community and equity are centered in scholarly publication (Aguado-Lopez & Becerril-Garcia, 2019).[16]

The slow progress of social movement organizations to ensure free access to scientific knowledge has inspired radical action. Out of growing frustration with journal paywalls, Sci-Hub was created by a computer programmer from Kazakhstan, Alexandra Elbakyan. This resource is an illegal, pirate repository of about 85% of all paywalled journal articles in existence up to 2020, when it stopped uploading papers in compliance with an injunction from an Indian court (Himmelstein et al., 2018).[17] Sci-Hub is not legal under international copyright law,[18] yet researchers unaffiliated with a well-funded university in the developed world cannot conduct research without it. The site has moved multiple times as their domains are shut down by commercial publishers whose content is illegally stored by Sci-Hub, and its founder hopes that by successfully arguing her case before and Indian court, she can continue to operate Sci-Hub legally under Indian law, and in effect, guarantee the human right to access research for free within India (Cummins, 2021).[19] Sci-Hub is a symptom of a broken system of scholarly publication that locks away scientific knowledge behind impossibly high textbook and journal paywalls. These are impossible for nearly all people to pay for in the course of a normal literature review, and thus, our broken system of scholarly publication necessitates that researchers use shadow libraries like Sci-Hub, Z-Library, and Library Genesis. It should not require mass-scale copyright infringement for the world to access scientific information.

The current model of scientific publishing privileges those already advantaged and raises important obstacles for those in oppressed groups to access and contribute to scientific knowledge or research-informed social change initiatives. For a more thorough, Black feminist perspective on scholarly publication see Eaves (2020).[20] As educators, it is your responsibility to use your information privilege—the access you have right now to the world’s knowledge and the skills you gain during your graduate education and post-graduate professional development—to fight for social change.

Being a responsible consumer of research

Education often involves accessing, creating, and otherwise engaging with social science knowledge to create change. On the micro-level, critical information literacy is needed to inform evidence-based decision-making in practice. On the meso- and macro-level, educators can use information literacy skills to give a voice for community concerns, help communities access and create the knowledge they need to foster change, or evaluate how well existing programs serving the community achieve their goals. Now that you are familiar with how to conduct ethical and responsible research and how to read the results of others’ research, you have an obligation to use your information literacy skills to create social change. This is part of critical information literacy: using your information privilege to address social injustices.

Collecting, sharing, and creating research findings for social change requires you to take seriously your identity as a social scientist. Doing so is in part a matter of being able to distinguish what you do know based on research findings from what you do not know. It is also a matter of having some awareness about what you can and cannot reasonably know.

When assessing social scientific findings, think about the information provided to you. Social scientists should be transparent with how they collected their data, ran their analyses, and formed their conclusions. These methodological details can help you evaluate the researcher’s claims. If, on the other hand, you come across some discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper, chances are that you will not find the same level of detailed information that you would find in a scholarly journal article. With secondary sources like news articles, it is hard to know enough about the study to be an informed consumer of information. Always read the primary source when possible.

Additionally, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most funders want, and in fact require, that recipients acknowledge them in publications. Keep in mind that some sources may not disclose who funds them. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the internet to see if you can learn more about the funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less influence on your thinking about your topic once you know if the funding posed a potential conflict of interest. The National Center for Responsive Philanthropy both supports progressive philanthropy (its own stated bias) and has documented conservative investment in building an ideological research infrastructure (see $1 Billion Dollars for Ideas).

There is some information that even the most responsible consumer of research cannot know. Because researchers are ethically bound to keep the identity of people in our study confidential, for example, we will never know exactly who participated in a given study or sometimes even in what location it was conducted. Awareness that you may never know everything about a study should provide some humility in terms of what we can “take away” from a given report of findings.

Unfortunately, researchers also sometimes engage in unethical behavior and do not disclose things that they should. For example, a recent study on COVID-19 (Bendavid et al., 2020)[21] did not disclose that it was funded by the chief executive of JetBlue, an airline company losing money from COVID-19 travel restrictions. It is alleged that this study was paid for by airline executives in order to provide scientific support for increasing the use of air travel and lifting travel restrictions. These conflicts of interest demonstrate that science is not distinct from other areas of social life that can be abused by those with more resources in order to benefit themselves.

COVID-19 is a particularly instructive case in spotting bad science. In a rapidly evolving information context, educators and others were forced to make decisions quickly using imperfect information. The Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, two of the most prestigious journals in medicine, had to retract two studies due to irregularities missed by pre-publication peer review despite the fact that the results had already been used to inform policy changes (Joseph, 2020).[22] At the same time, President Trump’s lies and misinformation about COVID-19 were a grave reminder of how information can be corrupted by those with power in the social and political arena (Paz, 2020).[23]

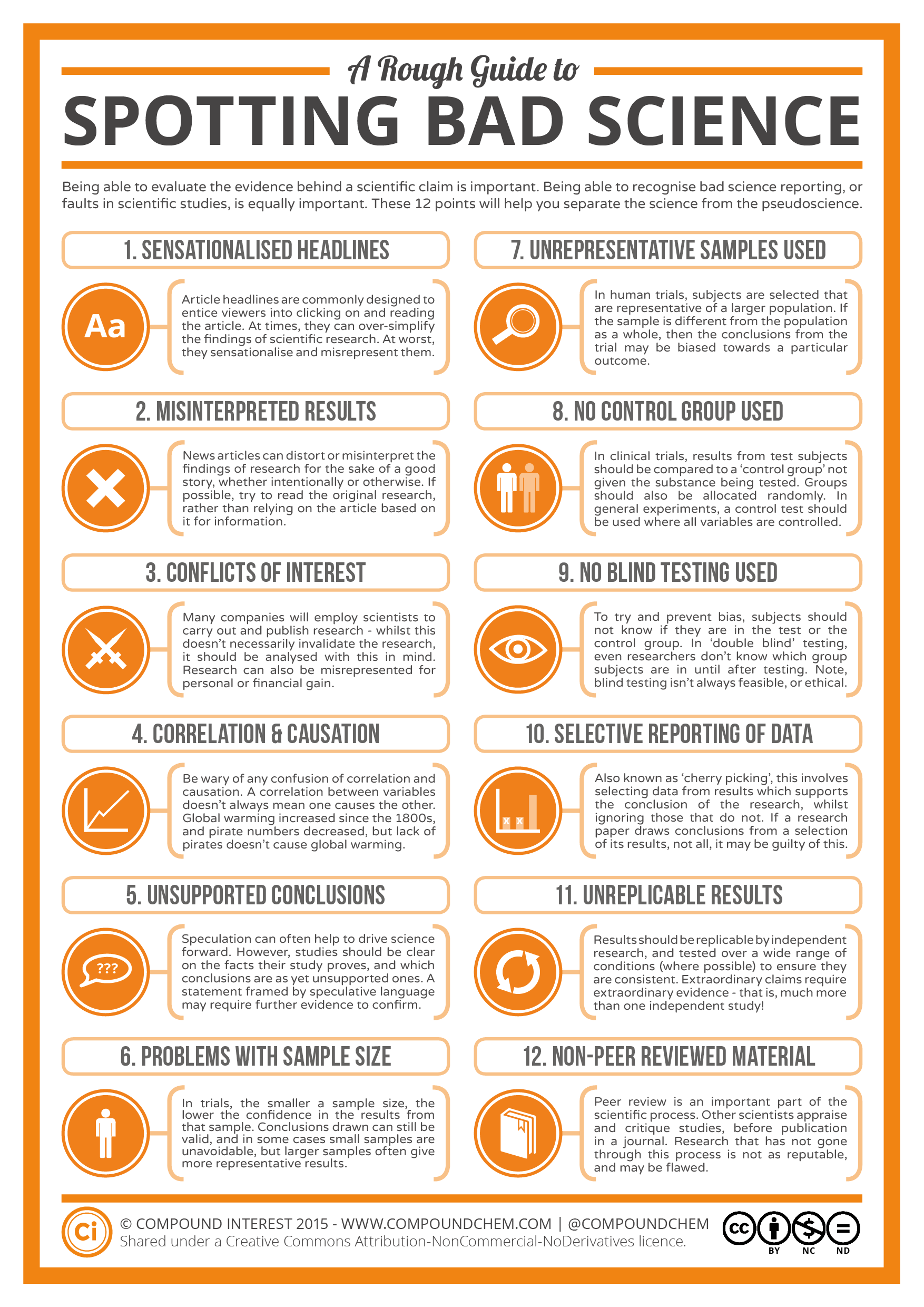

Figure 4.2 presents a rough guide to spotting bad science that is particularly useful when science has not had enough time for peer review and scholarly debate to thoroughly and systematically investigate a topic, as in the COVID-19 crisis. It is also a useful quick-reference guide for education practitioners who encounter new information about their topics from the news media, social media, or other informal sources of information like friends, family, and colleagues.

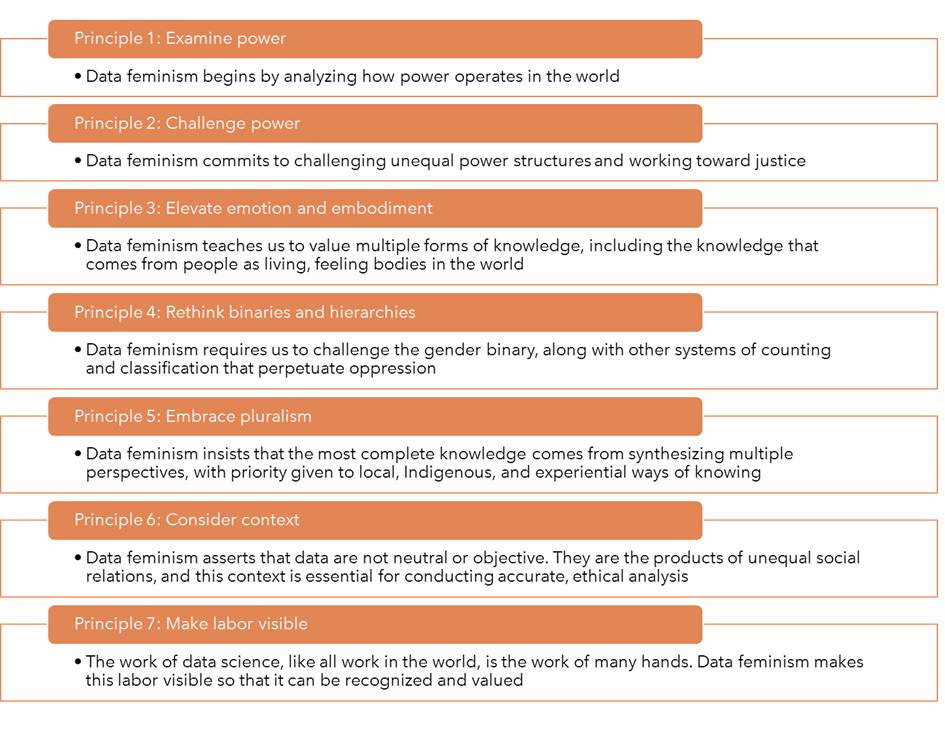

Feminist perspectives on science generally support the framework in Figure 4.2, but consider them to be incomplete, as they do not critique the scientific process itself. By drawing a line between science vs. pseudoscience, scientific inquiry can further social justice by using data to battle misinformation and uncover social inequities. However, feminist perspectives also draw our attention to historically overlooked aspects of the scientific process. D’ignazio and Klein (2020)[24] instead offer seven intersectional feminist principles for equitable and actionable COVID-19 data, as visualized in Figure 4.3.

Information literacy beyond scholarly literature

The research process we described in this chapter will help you arrive at an understanding of the scientific literature. However, that is not the only literature of value for researchers. For those conducting action research that engages more with communities and target populations, researchers are responsible not only for reviewing the scientific literature on their topic but also the literature that communities find important. If there are local newspapers, television shows, religious services or events, community meetings, or other sources of knowledge that your target population finds important, you should engage with those resources as well. Understanding these information sources builds empathetic understanding of participating groups and can help inform your research study. Moreover, they are likely to contain knowledge that is not a part of the scientific literature but is nevertheless crucial for conducting scientific research appropriately and effectively in a community.

Key Takeaways

- At this point, you should have a folder full of articles (at least a few dozen) that are relevant to your topic. Don’t worry! You won’t read all of them, but you will skim most of them for the most important information.

- Educators should develop critical information literacy. This helps us use social science knowledge for social change, and it critiques how current publishing models exclude and privilege different groups from accessing and creating knowledge.

- Education involves helping others understand social science and involves applying it in our practice. You must learn how to discriminate between reliable and unreliable information and apply your scientific knowledge to benefit your students and community.

Exercises

- Write a few sentences about what you think the answer to your working question might be.

- Identify at least five reputable sources of information from your literature search that provide evidence that what you wrote is true.

- What steps do you plan to take to demonstrate that you are helping others to understand social science and its relationship to your practice?

- Schimmer, R., Geschuhn, K. K., & Vogler, A. (2015). Disrupting the subscription journals’ business model for the necessary large-scale transformation to open access. doi:10.17617/1.3. ↵

- Mackenzie, L. (2018, October 4). Publishers escalate legal battle against ResearchGate. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/10/04/publishers-accuse-researchgate-mass-copyright-infringement ↵

- Schimmer, R., Geschuhn, K. K., & Vogler, A. (2015). Disrupting the subscription journals’ business model for the necessary large-scale transformation to open access. doi:10.17617/1.3. ↵

- McNeece, C. A., & Thyer, B. A. (2004). Evidence-based practice and social work. Journal of evidence-based social work, 1(1), 7-25. ↵

- Astley, W. G. (1985). Administrative Science as Socially Constructed Truth. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392694 ↵

- American Library Association (2020). Information literacy. Retrieved from: https://literacy.ala.org/information-literacy/ ↵

- Gregory, L. & Higgins, S. (eds.) (2013). Information literacy and social justice: Radical professional praxis. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. ↵

- Tewell, E. (2016). Putting critical information literacy into context: How and why librarians adopt critical practices in their teaching. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from: http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/putting-critical-information-literacy-into-context-how-and-why-librarians-adopt-critical-practices-in-their-teaching/ ↵

- Booth, C. (2017, November 9). Open access, information privilege, and library work. OCLC Distinguished Seminar Series. Retrieved from: https://www.oclc.org/research/events/2017/11-09.html ↵

- Robinson-Garcia, N., Costas, R., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2020). Open Access uptake by universities worldwide. PeerJ, 8, e9410. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9410. ↵

- RELX (20`19). Annual report and financial statements 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.relx.com/~/media/Files/R/RELX-Group/documents/reports/annual-reports/2018-annual-report.pdf ↵

- After a year or so, your login will no longer work with the library. It's sincerely too expensive for your university to afford lifetime access to journal articles for all graduates, though it is certainly understandable why students would expect differently. SFU does maintain a Community Scholars Program to help break down these access barriers. ↵

- Appadurai, A. (2006). The right to research. Globalisation, societies and education, 4(2), 167-177. ↵

- Arunachalam, S. (2017). Social justice in scholarly publishing: Open access is the only way. The American Journal of Bioethics, 17(10), 15-17. ↵

- Bali, M., & Caines, A. (2018). A call for promoting ownership, equity, and agency in faculty development via connected learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 46.; Eaves, L. E. (2020). Power and the paywall: A Black feminist reflection on the socio-spatial formations of publishing. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. ↵

- Aguado-López, E., & Becerril-Garcia, A. (2019). AmeliCA before Plan S–The Latin American Initiative to Develop a Cooperative, Non-Commercial, Academic Led, System of Scholarly Communication. Retrieved from: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2019/08/08/amelica-before-plan-s-the-latin-american-initiative-to-develop-a-cooperative-non-commercial-academic-led-system-of-scholarly-communication/ ↵