3

Chapter Outline

- The scholarly literature (26 minute read)

- Searching basics (23 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to school discipline, mental health, gender-based discrimination, police shootings, ableism, autism and anti-vaccination conspiracy theories, children’s mental health, child abuse, poverty, substance use disorders and parenting/pregnancy, and tobacco use.

3.1 The scholarly literature

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define what we mean by “the literature”

- Differentiate between primary and secondary sources and summarize why researchers use primary sources

- Distinguish between different types of resources and how they may be useful for a research project

- Identify different types of journal articles

In the last chapter, we discussed how looking at the literature on your topic is the first thing you will need to do as part of a student research project. A literature review makes up the first half of a research proposal. But what do we mean by “the literature?” The literature consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation on a specific topic within and between disciplines. You will find in “the literature” documents that track the progression of the research and background of your topic. You will also find controversies and unresolved questions that can inspire your own project. By this point in your academic career, you’ve probably heard that you need to get “peer-reviewed journal articles.” But what are those exactly? How do they differ from news articles or encyclopedias? That is the focus of this section of the text—different types of literature.

Disciplines

Information does not exist in the environment like some kind of raw material. It is produced by individuals working within a particular field of knowledge who use specific methods for generating new information, or a discipline. Disciplines consume, produce, and share knowledge. Looking through a university’s course catalog gives clues to disciplinary structure. Fields such as political science, biology, history, and mathematics are unique disciplines, as is education. We have things we study often, like education policy, pedagogy, leadership, or psychology, and a particular theoretical and ethical framework through which we view the world.

Education researchers must take an interdisciplinary perspective, engaging with not just the education literature but literature from many disciplines to gain a comprehensive and accurate understanding of a topic. Consider how nursing and education would differ in studying sports in schools. A nursing researcher might study how sports affect individuals’ health and well-being, how to assess and treat sports injuries, or the physical conditioning required for athletics. An education researcher might study how schools privilege or punish student athletes, how athletics impact social relationships and hierarchies, or the differences in participation in organized sports between children of different genders. People in some disciplines are much more likely to publish on sports in schools than those in others, like political science or religious studies. I’m sure you can find a bit of scholarship on sports in schools in most disciplines, though you will want to target disciplines that are likely to address the topic often as part of the core purpose of the profession (like sports medicine or sports education). Sometimes disciplines overlap in their focus, as teaching, career counselling and counselling psychology, or urban planning and public administration.

You will need to become comfortable with identifying the disciplines that might contribute information to any literature search. When you do this, you will also learn how to decode the way people talk about a topic within a discipline. This will be useful to you when you begin a review of the literature in your area of study.

Exercises

Think about your research topic and working question that you created in Chapter 2. What disciplines are likely to publish about your topic?

For each discipline, consider:

- What is important about the topic to scholars in that discipline?

- What is most likely to be the focus of their study about the topic?

- What perspective are they most likely to have on the topic?

Periodicals

First, let’s discuss periodicals. Periodicals include trade publications, magazines, and newspapers. While they may appear similar, particularly those that are found online, each of these periodicals has unique features designed for a specific purpose. Magazine and newspaper articles are usually written by journalists, are intended to be short and understandable for the average adult, contain color images and advertisements, and are designed as commodities to be sold to an audience. An example of useful a magazine for educators would be Education Week.

Primary sources

Periodicals may contain primary or secondary literature depending on the article in question. An article that is a primary source gathers information as an event happens (e.g. an interview with a victim of a local fire), or it may relay original research reported on by the journalists (e.g. the Guardian newspaper’s The Counted webpage which tracked how many people were killed by police officers in the United States from 2015-2016).[1] Primary sources are based on raw data, which we discussed in Chapter 2.

Is it okay to use a magazine or newspaper as a source in your research methods class? If you were in my class, the answer is “probably not.” There are some exceptions, such as the Guardian page mentioned above (which is a great example of data journalism) or breaking news about a policy or community, but most of what newspapers and magazines publish is secondary information. Researchers should look for primary sources—the original source of information—whenever possible.

Secondary sources

Secondary sources interpret, discuss, and summarize primary sources. Examples of secondary sources include literature reviews written by researchers, book reviews, as well as news articles or videos about recently published research. Your job in this course is to read the original source of the information, the primary source. When you read a secondary source, you are relying on another’s interpretation of the primary source. That person might be wrong in how they interpret the primary source, or they may simply focus on a small part of what the primary source says.

Most often, I see the distinction between primary and secondary sources in the references pages students submit for the first few assignments in my research class. Students are used to citing the summaries of scientific findings from periodicals like the Vancouver Sun, Globe and Mail, or National Post. Instead, students should read the original journal article written by the researchers, as it is the primary source. Journalists are not scientists. If you have seen articles about how chocolate cures cancer or how drinking whiskey can extend your life, you should understand how journalists can exaggerate or misinterpret scientific results. See this cartoon from Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal for a hilarious illustration of sensationalizing findings from scientific research in journalism. Even when news outlets do a very good job of interpreting scientific findings, and that is certainly what most journalistic outlets strive for, you are still likely to only get a short summary of the key results.

When you are getting started with research, newspaper and magazine articles are excellent places to commence your journey into the literature, as they do not require specialized knowledge and may inspire deeper inquiry. Just make sure you are reading news, not opinion pieces, which may exclude facts that contradict the author’s viewpoint. As we will talk about in the next chapter, the one secondary source that is highly valuable for student researchers are review articles published in academic journals, as they summarize much of the relevant literature on a topic.

Trade publications

Unlike magazines and newspapers, trade publications may take some specialized knowledge to understand. Trade publications or trade journals are periodicals directed to members of a specific profession. They often include information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field. Because of this, trade publications are somewhat more reputable than newspapers or magazines, as the authors are specialists in their field.

Kappan Magazine and Educational Leadership are good examples of trade publications in education. The intended audiences are teachers, teacher leaders, and administrators who want to learn about important practice issues. They report news and trends in a particular field but not necessarily original scholarly research. They may also provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements.

So, can you use trade publications in a formal research proposal? Again, if you’re in my class, the answer would be “probably not.” A main shortcoming of trade publications is the lack of peer review. Peer review refers to a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field. Peer review is part of the cycle of publication for journal articles and provides a gatekeeper service, so to speak, which (in theory) ensures that only top-quality articles are published.

In reality, there are a number of problems with our present system of peer review. Briefly, critiques of the current peer review system include unreliable feedback across reviewers; inconsistent error and fraud detection; prolonged evaluation periods; and biases against non-dominant identities, perspectives, and methods. It can take years for a manuscript to complete peer review, likely with one or more rounds of revisions between the author and the reviewers or editors at the journal. See Kelly and colleagues (2014)[2] for an overview of the strengths and limitations of peer review.

A trade publication isn’t as reputable as a journal article because it does not include expert peer review. While trade publications do contain a staff of editors, the level of review is not as stringent as with academic journals. On the other hand, if you are completing a study about practitioners, then trade publications may be highly relevant sources of information for your proposal.

In summary, newspapers and other popular press publications are useful for getting general topic ideas. Trade publications are useful for practical application in a profession and may also be a good source of keywords for future searching.

Journal articles

As you’ve probably heard by now, academic journal articles are considered to be the most reputable sources of information, particularly in research methods courses. Journal articles are written by scholars with the intended audience of other scholars (like you!). The articles are often long and contain extensive references that support the author’s arguments. The journals themselves are often dedicated to a single topic, like leadership, policy or curriculum theory, and include articles that seek to advance the body of knowledge about a particular topic. We included a list of popular journals in Chapter 1.

Peer review

Most journals are peer-reviewed (also known as refereed), which means a panel of scholars reviews the articles to provide a recommendation on whether they should be accepted into that specific journal. Scholarly journals make available articles of interest to experts or researchers. An editorial board of respected scholars (i.e., peers) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. Editors and volunteer reviewers decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and should be published. For this reason, journal articles are the main source of information for researchers as well as for literature reviews. Usually, peer review is done confidentially, with the reviewer’s name hidden from the author and vice versa. This confidentiality is mediated by the editorial staff at an academic journal and is termed blinded review, though this ableist language should be revised to confidential review (Ades, 2020).[3]

You can usually tell whether a journal is peer reviewed by going to its website. Under the “About Us” or “Author Submission” sections, the website should list the procedures for peer review. If a journal does not provide such information, you may have found a “predatory journal.” You may want to check with your professor or a librarian, as the websites for some reputable journals are not straightforward. It is important not to use articles from predatory journals. These journals will publish any article—no matter how bad it is—as long as the author pays them. If a journal appears suspicious and may be a predatory publication, search for it in the COPE member list. Another predatory publishing resource, Beall’s List, has been critiqued as discriminatory towards some open access publishing models and non-Western publishers so we do not recommend its use (Berger & Cirasella, 2015).[4]

Even reputable, non-predatory journals publish articles that are later shown to be incorrect, unethically manipulated, or otherwise faulty. In Chapter 1, we talked about Andrew Wakefield’s fabricated data linking autism and vaccines. His study was published in The Lancet, one of the most reputable journals in medicine, who formally retracted the article years later. Retraction Watch is a scholarly project dedicated to highlighting when scientific papers are withdrawn and why. It is important to note that peer review is not a perfect process, and that it is subject to error. There is a growing movement to make the peer review process faster and more transparent. For example, 17 life science journals moved to a model of publishing the unreviewed draft, the reviewer’s comments, and how they informed the final draft (Brainard, 2019).[5]

Seminal articles

Peers don’t just review work prior to publication. The whole point of publishing a journal article is to ensure that your peers will read it and use it in their work. A seminal article is “a classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge” (Houser, 2018, p. 112).[6] Basically, it is a really important article. Because of the diversity of the field of education there are hundreds of articles that might be considered seminal.

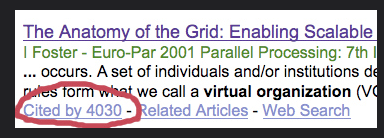

How do you know if you are looking at a seminal article? Seminal articles are cited a lot in the literature. You can see how many authors have cited an article using Google Scholar’s citation count feature when you search for the article, as depicted in Figure 3.1. Generally speaking, articles that have been cited more often are considered more influential in the field although there is nothing wrong with citing an article with a low citation count.

Figure 3.1 shows a citation count for an article that is obviously seminal, with over 4,000 citations. There is no exact number of citations at which an article is considered seminal. A low citation count for an article published last year is not a reliable indicator of the importance of this article to the literature, as it takes time for people to read articles and incorporate them into their scholarship. For example, if you are looking at an article from five years ago with 20 citations, that’s still a good quality resource to use. The purpose here is to recognize when articles (and authors) are clearly influential in the literature, and are therefore more likely to be important to your review of the literature in that topic area.

Empirical articles

Journal articles can fall into one of several categories. Empirical articles report the results of a quantitative or qualitative analysis of raw data conducted by the author. Empirical articles also integrate theory and previous research. However, just because an article includes quantitative or qualitative results does not necessarily mean it is an empirical journal article. Since most articles contain a literature review with findings from empirical studies, you need to make sure the findings reported in the study stem from the author’s analysis of raw data.

Fortunately, empirical articles follow a similar structure, and include the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion—in that order. While the exact wording in the headings may differ slightly from publication to publication and other sections may be added, this general structure applies to nearly all empirical journal articles. If you see this general structure, you are reading an empirical journal article. You can see this structure in a recent article from the open access education journal, the International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership (IJEPL). Walker & Kutsyuruba (2019)[7] conducted a mixed-methods pan-Canadian study that examined the differential impact of teacher induction and mentorship programs on the retention of early career teachers. The manuscript begins with an “Introduction” heading on page one, Review of the Literature on page two, Research Methodology on page three, Findings on page six and Discussion on page 13, with a Conclusion on page 16. Because this is a mixed-methods empirical article, the results section is full of themes and quotes based on what participants said in their interviews with researchers as well as a reporting out of survey results. If it were a quantitative empirical article, like this one from Kelly, Kubart, and Freed (2020)[8], the results section would be limited to statistical data, tables, and figures that indicated mathematical relationships between the key variables in the research question.

While this article uses the traditional headings, you may see other journal articles that use headings like “Background” instead of “Introduction” or “Findings” instead of “Results”. You may also find headings like “Conclusions”, “Implications”, “Limitations”, and so forth in other journal articles. Regardless of the specific wording, empirical journal articles follow the structure of introduction, methods, results, and discussion. If it has a methods and results section, it’s almost certainly an empirical journal article. However, if the article does not have these specific sections, it’s likely you’ve found a non-empirical article because the author did not analyze any raw data.

Review articles

Along with empirical articles, review articles are the most important type of article you will read as part of conducting your review of the literature. We will discuss their importance more in Chapter 4, but briefly, review articles are journal articles that summarize the findings of other researchers and establish the state of the literature in a given topic area. They are so helpful because they synthesize a wide body of research information in a (relatively) short journal article. Review articles include literature reviews, like this one from Reynolds & Bacon (2018)[9] which summarizes the literature on integrating refugee children in schools. You may find literature reviews with a special focus like a critical review of the literature, which may apply a perspective like critical theory or feminist theory while surveying the scholarly literature on a given topic.

Review articles also include systematic reviews, which are like literature reviews but more clearly specify the criteria by which the authors search for, include, and analyze the content of the scholarly literature in the review (Uman, 2011).[10] For example, Laitsch, Nguyen and Younghusband conducted a scoping review of the literature on class size in schools as part of the BCTF’s 2010 Supreme Court challenge.[11]. We synthesized the results of 112 studies of class size to answer the question, “What is the current state of knowledge regarding the impact of class size on learning conditions of students in elementary and secondary schools?” As you can see in Figure 1 of this article, systematic reviews are very specific about which articles they include in their analysis. Because systematic reviews try to address all scholarly literature published on a given topic, researchers specify how the literature search was conducted, how many articles were included or excluded, and the reasoning for their decisions. This way, researchers make sure there is no relevant source excluded from their analysis.

The two final kinds of review articles, meta-analysis and meta-synthesis go even further than systematic reviews in that they analyze the raw data from all of the articles published in a given topic area, not just the published results. A meta-analysis is a study that combines raw data from multiple sources and analyzes the pooled data using statistics. Meta-analyses are particularly helpful for intervention studies, as it will pool together the raw data from multiple samples and studies to create a super-study of thousands of people, which has greater explanatory power. For example, this recent meta-analysis by Graham and colleagues (2016)[12] analyzes pooled data from 47 separate studies on balanced literacy instruction to see if it is effective (spoiler alert, it is).

A meta-synthesis is similar to a meta-analysis but it pools qualitative results from multiple studies for analysis. For example, this recent meta-synthesis by Pidgeon and Riley (2021)[13] explores how principles of Indigenous research methodologies informed research relationships with Indigenous communities by qualitatively analyzing and synthesizing the results of 79 relevant research studies. While meta-analyses and meta-syntheses are the most methodologically robust type of review article, any recently published review article that is highly relevant to your topic area is a good place to start reading literature. Because review articles synthesize the results of multiple studies, they can give you a broad sense of the overall literature on your topic. We’ll review a few kinds of non-empirical articles next.

Theoretical articles

Theoretical articles discuss a theory, conceptual model, or framework for understanding a problem. They may delve into philosophical or ethical analysis as well. For example, this theoretical article by Ryan and Deci (2020)[14] discusses intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and the importance of understanding motivation across educational levels and cultural contexts. While most students know they need to have statistics to back up what they think is true, it’s also important to use theory to inform what you think about your topic. Theoretical articles can help you understand how to think about a topic and may help you make sense of the results of empirical studies.

Practical articles

Practical articles describe “how things are done” from the perspective of on-the-ground practitioners. They are usually shorter than other types of articles and are intended to inform practitioners of a discipline on current issues. They may also reflect on a “hot topic” in the practice domain, a complex client situation, or an issue that may affect the profession as a whole. This practical article by Kajander and colleagues (2019)[15] describes the work a one high school team in designing, developing, supporting, and field-testing a numeracy and general learning skills course.

| Type of journal article | How do you know if you’re looking at one? | Why is this type of article useful? |

| Peer-reviewed | Go to the journal’s website, and look for information that describes peer review. This may be in the instructions for authors or about the journal sections. | To ensure other respected scholars have reviewed, provided feedback, and approved this article as containing honest and important scientific scholarship. |

| Article in a predatory journal | Use the SIFT method. Search for the publisher and journal on Wikipedia and in a search engine. Check the COPE member list to see if your journal appears there. | They are not useful. Articles in predatory journals are published for a fee and have not undergone serious review. They should not be cited. |

| *Not an journal article* | Does not provide the name of the journal it is published in. You may want to google the name of the article or report and its author to see if you can find a published version. | Journal articles aren’t everything, but if your instructor asks for one, make sure you haven’t mistakenly use dissertations, theses, and government reports. |

| Empirical article | Most likely, if it has a methods and results section, it is an empirical article. | Once you have a more specific idea in mind for your study, you can adapt the measures, design, and sampling approach of empirical articles (quantitative or qualitative). The introduction and results section can also provide important information for your literature review. Make sure not to rely too heavily on a single empirical study, though, and try to build connections across studies you read. |

| Quantitative article | The methods section contains numerical measures and instruments, and the results section provides outcomes of statistical analyses. | |

| Qualitative article | The methods section describes interviews, focus groups, or other qualitative techniques. The results section has a lot of quotes from study participants. | |

| Review article | The title or abstract includes terms like literature review, systematic review, meta-analysis, or meta-synthesis. | Getting a comprehensive but generalized understanding of the topic and identifying common and controversial findings across studies. |

| Theoretical article | The articles does not have a methods or results section. It talks about theory a lot. | Developing your theoretical understanding of your topic. |

| Practical articles | Usually in a section at the front or back of the journal, separate from full articles. It addresses hot topics in the profession from the standpoint of a practitioner. | Identifying how practitioners in the real world think about your topic. |

| Book reviews, notes, and commentary | Much shorter, usually only a page or two. Should state clearly what kind of note or review they are in the title, abstract, or keywords. | Can point towards sources that provide more substance on the topic you are studying or point out emerging or controversial aspects of your topic. |

What kind of articles should you read?

No one type of article is better than the other, as each serves a different purpose. Seminal articles relevant to your topic area are important to read because the ideas in them are deeply influential in the literature. Theoretical articles will help you understand the social theory behind your topic. Empirical articles should test those theories quantitatively or create those theories qualitatively, a process we will discuss in greater detail in Chapter 8. Review articles help you get a broad survey of the literature by summarizing the results of multiple studies, which is particularly important at the beginning of a literature search. And finally, practical articles will help you understand a practitioner’s on-the-ground experience. Pick the kind of article that gives you the kind of information you need.

Other sources of information

As I mentioned previously, newspaper and magazine articles are good places to start your search (though they should not be the end of your search!). Another source students go to almost immediately is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is a marvel of human knowledge. It is a digital encyclopedia to which anyone can contribute. The entries for each Wikipedia article are overseen by skilled and specialized editors who volunteer their time and knowledge to making sure their articles are correct and up to date. That said, Wikipedia has been criticized for gender and racial bias as well as inequities in the treatment of the Global South (Montgomery et al., 2021).[16]

Encyclopedias

Wikipedia is an example of a tertiary source. We reviewed primary and secondary sources in the previous section. Tertiary sources review primary and secondary sources. Examples of tertiary sources include encyclopedias, directories, dictionaries, and textbooks like this one. Tertiary sources are also an excellent place to start (but also not a good place to end) your search. A student might consult Wikipedia or the International Encyclopedia of Education to get a general idea of an education topic. Encyclopedias can also be excellent resources for their citations, and often the citations will be to seminal articles or important primary sources.

The difference between secondary and tertiary sources is not exact, and as we’ve discussed, using one or both at the beginning of a project is a good idea. As your study of the topic progresses, you will naturally have to transition away from secondary and tertiary sources and towards primary sources. We’ve already talked about one particular kind of primary source—empirical journal articles. We will spend more time on this primary source than any other in this textbook. However, it is important to understand how other types of sources can be used as well.

Books

Books contain important scholarly information. They are particularly helpful for theoretical, philosophical, and historical inquiry. For example, in my research on the public understanding of the purpose for public education I worked with colleagues to engage with numerous lay-people in the U.S. and Canada and bring their voices into the discussion. The complexity of the topic and the diversity of voices meant that a book-length project was needed. You can use books to learn key concepts, theories, and keywords you can use to find more up-to-date sources. They may also help you understand the scope and foundations of a topic and how it has changed over time.

Some books contain chapters that look like academic journal articles. These are called edited volumes. They contain chapters similar to journal articles, but the content is reviewed by an editor rather than peer reviewers. Such books often allow for a more summary overview of research, rather than a focusing on singular studies, providing a broader picture of the topic. However, because these types of summaries are not systematic, they should be used with care, as they may over-emphasize the beliefs and opinions of the book’s authors and editors.

Conference proceedings and presentations

Conferences provide a great source of information. At conferences such as the the Canadian Society for the Study of Education (CSSE) Annual Meeting or the American Education Research Association, researchers present papers on their most recent research. The papers presented at conferences are sometimes published in a volume called a conference proceeding, though these are not common in education. Conference proceedings highlight the current discourse in a discipline and can lead you to scholars who are interested in specific research areas. Individual papers are often available for download if you are a member of the organization, or if you e-mail the authors directly.

A word about conference papers: several factors may render these documents difficult to find. It is not unusual that papers delivered at professional conferences are not published in print or electronic form, although an abstract may be available. In these cases, the full paper may only be available from the author or authors. The most important thing to remember is that if you have any difficulty finding a conference proceeding or paper, ask a librarian for assistance.

Gray literature

Another source of information is the gray literature, which consist of research reports released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think tanks. If you have already taken a policy class, perhaps you’ve come across the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternative (CCPABC). The CCPA is a think tank—a group of scholars that conducts research and advocates for political, economic, and social change. Similarly, students often find the Centers for Disease Control website helpful for understanding the prevalence of social problems like mental illness, school health, and child abuse. If you find fact sheets, news items, blog posts, or other content from organizations like think tanks or advocacy organizations in your topic area, look at the references cited to find the primary source, rather than citing the secondary source (the fact sheet). While you might be persuaded by their arguments, you want to make sure to account for the author’s potential bias.

Think tanks and policy organizations often have a specific viewpoint they support. For example, there are conservative, liberal, and libertarian think tanks. Policy organizations may be funded by donors to push a given message to the public. Government agencies are generally more objective, though they may be less critical of government programs than other sources might be. Similarly, agencies may be less critical in the reports they share with the public. The main shortcoming of gray literature is the lack of peer review that is found in academic journal articles. Government reports are often cited in research proposals, along with some reports from policy organizations.

Dissertations and theses

Dissertations and theses can be rich sources of information and include extensive reference lists you can use to scan for resources. However, dissertations and theses are considered gray literature because they are not independently peer reviewed. The accuracy and validity of the document itself may depend on the school that awarded the doctoral or master’s degree to the author. Having completed a dissertation, I can attest to the length of time they take to write as well as read. If you come across a relevant dissertation, it is a good idea to read the literature review and note the sources the author used so you can incorporate them into your literature review. The data analysis found in these sources may be less useful as it has not passed through independent peer review yet; however, dissertations are approved by committees of scholars, so they are considered more reputable than sources that lack review by experts prior to publication. Consider searching for journal articles by the dissertation’s author to see if any of the results have been peer reviewed and published. You will also be thankful because journal articles are much shorter than dissertations and theses!

Webpages

The final source of information we are going to talk about is webpages. Webpages will help you locate professional organizations and human service agencies that address your problem, and there are often personal web pages discussion issues of interest in education. Looking at social media feeds, reports, publications, or “news” sections on an organization’s webpage can clue you into important topics to study. Because anyone can develop their own webpage, there are also a large number of education-related websites. They are usually not considered scholarly sources to use in formal writing, as they only represent the opinions, beliefs, and values of the sponsoring individual or organization, but they may be useful as you are first learning about a topic. Additionally, many advocacy webpages will provide references for the facts they site, providing you with the primary source. Keep in mind too that webpages can be tricky to quote and cite, as they can be updated or moved at any time. While some reputable sources will include editing notes, others may not. Webpages can be updated without notice.

Use quality sources

We will discuss more specific criteria for evaluating the quality of the sources you choose in section 4.1. For now, as you access and read each source you encounter, remember:

All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious. You should consider criteria such as the type of source, its intended purpose and audience, the author’s (or authors’) qualifications, the publication’s reputation, any indications of bias or hidden agendas, how current the source is, and the overall quality of the writing, thinking, and design. (Writing for Success, 2015, p. 448).[17]

While each of these sources provides an important facet of our learning process, your research should focus on finding academic journal articles about your topic. These are the primary sources of the research world. While it may be acceptable and necessary to use other primary sources—like books, government reports, or an investigative article by a newspaper or magazine—academic journal articles are preferred. Finding these journal articles is the topic of the next section.

Key Takeaways

- News articles, Wikipedia, and webpages are a good place to start learning about a new topic, but you should rely on more reputable and peer-reviewed sources when reviewing “the literature” on your topic.

- Researchers should read and cite primary sources, tracing a fact or idea to its original source. If you read a news article or webpage that talks about a study or report (i.e., a secondary source), read the primary source to get all the facts.

- Empirical articles report quantitative or qualitative analysis completed by the author on raw data.

- You must critically assess the quality and bias of any source you read. Just because it’s published doesn’t mean it’s true.

Exercises

Conduct a general Google search on your topic.

- Identify whether the first 10 sources that come up are primary or secondary sources.

- Optionally, ask a friend to conduct the same Google search and compare your results. Google’s search engine customizes the results you see based on your browsing history and other data the company has collected about you. This is called a filter bubble, and you can learn more about it in this Ted Talk about filter bubbles.

Find a secondary or tertiary source about your topic.

- Trace one to the original, primary source.

Find a review article in your topic area.

- Identify which kind it is (literature review, systematic review, meta-analysis, etc.)

Find a think tank, advocacy organization, or website that addresses your topic.

- Using their information, identify primary sources that might be of use to you. Consider adding them to your social media feed or joining an email newsletter.

3.2 Searching basics

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Brainstorm potential keywords and search queries for your topic

- Apply basic Boolean search operators to your search queries

- Identify relevant databases in which to search for journal articles

- Target your search queries in databases to the most relevant results

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our recliners. This is certainly true of familiarizing yourself with the literature. Most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to all of the literature you’ll ever need on your topic.

Unfortunately, even though many college classes require students to find and use academic journal articles, there is little training for students on how to do so. The purpose of this section and the rest of part 1 of the textbook is to build information literacy skills, which are the basic building blocks of any research project. While we describe the process here as linear, with one step following neatly after another, in reality, you will likely go back to Step 1 often as your topic gets more specific and your working question becomes clearer. Recall our diagram in the last chapter, Figure 2.1. You are cycling between reformulating your working question then searching for and reading the literature on your topic.

Step 1: Get organized

The process of searching databases and revising your working question can be time-consuming, so it is a good idea to write notes to yourself. Remembering why you included certain search terms, searched different databases, or other decisions in the literature search process can help you keep track of what you’ve done. You can then recreate searches to download articles you may have missed or remember reflections you had weeks ago when you last conducted a literature search.

- When I search the literature, I create a “working document” in a word processor where I write notes and reflections on the databases, search process, keywords and terms I use so that I can recreate searches if needed.

- Most databases allow you to download the articles to your computer. I have an entire library of articles in subject area

folders on my computer for easy retrieval. - It is also helpful to build a spreadsheet or database file with basic article information for easy reference: author, title, abstract, key findings relevant to your work. This Annotated Bibliography (see 4.2 Annotating sources) can help you manage the large amount of information you’re collecting for easy use later in the writing process.

Step 2: Build search queries using keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something in a search engine like Google or Bing? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need more quickly, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want. The danger in being a question-asker or typing like you talk is that including too many extraneous words will confuse the search engine. In this section, you will learn to use keywords rather than natural language to find scholarly information.

Keywords are the words or phrases you use in your search query, and they inform the relevance and quantity of results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different terms to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as testing, rather than assessment (for example). Think about what keywords are important to answering your working question. Are there other ways of expressing the same idea?

Often in education research, there is a bit of jargon to become familiar with when crafting your search queries. For example, if you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include the word “parentification” as part of your search query. As graduate researchers, you are not expected to know these terms ahead of time. Instead, start with the keywords you already know. As you read more about your topic and become familiar with some of these words, begin including these keywords into your search results, as they may return more relevant hits. In some articles, there will be a list of keywords after the abstract, or you can pick them out of the abstract for further follow up.

Exercises

- List all of the keywords you can think of that are relevant to your working question.

- Add new keywords to this list as you are searching and learn more about your topic.

- Start a document in your research journal in which you can put your keywords as well as your notes and reflections on the search process.

Boolean searching: Learn to talk like a robot

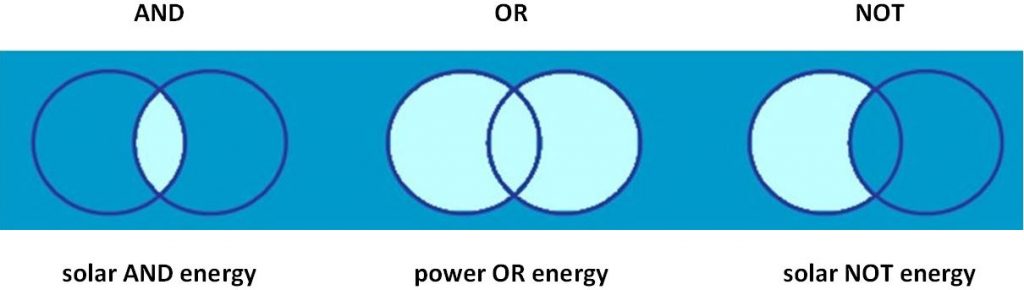

Google is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, utilizes that same approach. However, other databases that are important for education research—such as Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, and Education Source—will not return useful results if you ask a question or type a sentence or phrase as your search query. Instead, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “what are the effects of class size reduction on student behaviour,” you might type in “class size AND behaviour”. [Note: you would not actually use the quotation marks in your search query for the examples in this subsection, but you might use them around “class size”].

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “class size AND behaviour” returns articles that mention both class size and behaviour. There are lots of articles on class size and lots of articles on behaviour, but fewer articles on that address both of those topics. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present. In cases here I am getting a lot of non-education returns, sometimes adding ubiquitous education words like “teacher” or “school” can limit out other non-relevant returns.

The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to class size at the post-secondary level. Searching for “class size AND behaviour NOT undergraduate” or “class size AND behaviour NOT graduate” would exclude articles that mentioned undergraduate or graduate students. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “class size OR behaviour” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in Figure 3.2 below.

Exercises

- Build a simple Boolean search query, appropriately using AND, OR, and NOT.

- Experiment with different Boolean search queries by swapping in different keywords.

- Write down which Boolean queries you create in your notes.

Step 3: Find the right databases

Queries are entered into a database or a searchable collection of information. In research methods, we are usually looking for databases that contain academic journal articles. Each database has a unique focus and presents distinct advantages or disadvantages. It is important to try out multiple databases, and experiment with different keywords and Boolean operators to find the most relevant results for your working question.

Google Scholar

The most commonly used public database of scholarly literature is Google Scholar, and there are many benefits to using it. Most importantly, Google Scholar is free and is the only database to which you will have access after you graduate. Building competence at using it now will help you as you engage in the evidence-based practice process post-graduation. Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, it can seem less intimidating. However, Google Scholar also understands Boolean search terms and contains some advanced searching features like searching within one specific author’s body of work, one journal, or searching for keywords in the title of the journal. We have previously mentioned the ‘Cited By’ field which counts the number of other publications that cite the article and a link to explore and search within those citing articles. This can be helpful when you need to find more recent articles about the same topic.

I often use their citation generator, though I have to fix a few things on most entries before using them in my references. You can also set email alerts for a specific search query, which can help you stay current on the literature over time, and organize journal articles into folders. If these advanced features sound useful to you, consult Google Scholar Search Tips for a walkthrough.

While these features are great, there are some limitations to Google Scholar. The sources in Google Scholar are not curated by a professional body like the American Psychological Association (who curates PsycINFO). Instead, Google crawls the internet for what it thinks are scholarly works and indexes them in their database. When you search in Google Scholar, the sources will be not only journal articles, but books, government and foundation reports, gray literature, graduate theses, and articles that have not undergone peer review. There is no way to select for a specific type of source, and you need to look clearly and identify what kind of source you are reading. Not every source on Google Scholar is reputable or will match what you need for an assignment.

With that broad focus, Google Scholar ranks the results from your query by the number of times each source was cited by other scholars and the number of times your keywords are mentioned in the source. This biases the search results towards older, more seminal articles. So, you should consider limiting your results to only those published the last few years. Unfortunately, Google Scholar also lacks advanced searching features of other databases, like searching by subject area or within the abstract of an article.

The last major limitation of Google is that the articles returned are often held behind paywalls. A great work around is to simply paste the title into the SFU library search window. If that doesn’t work, you can also search for the specific journal.

Exercises

- Type your queries into Google Scholar. See which queries provide you with the most relevant results.

- Look for new keywords in the results you find, particularly any jargon used in that topic area you may not have known before.

- Write down notes on which queries and keywords work best. Reflect on what you read in the abstracts and titles of the search results in Google Scholar.

Databases accessed via an institution

Although learning Google Scholar is important, you should take advantage of the databases to which your institution purchases access. The first place to look for education scholarship is Education Source, as this databases is indexed specifically for the discipline of education. As you are aware, Education is interdisciplinary by nature, and it is a good idea not to limit yourself solely to the education literature on your topic. If your study requires information from the disciplines of psychology, social work, or medicine, you will likely find the databases PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and PubMed (respectively) to be helpful in your search.

There are also less specialized databases that contain articles from across education and other disciplines. Academic Search Premier is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines. Within Academic Search Premier, you can click Choose Databases to select databases that apply to different disciplines or topic areas.

It is worth mentioning that many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches some of the databases to which they have access, including both disciplinary and interdisciplinary databases. Meta-search engines are fantastic, but you must be careful to narrow your results down to the type of resource you are looking for, as they will include all types of media (e.g., books, movies, games). Unfortunately, not every database is included in these meta-search engines, so you will want to try other databases, as well.

You can find the databases we mentioned here and others on the Databases page of your university library (at SFU, the page is here). A university login is required to for you to access these databases because you pay for access as part of the tuition and fees at your university. This means that sometime after graduation, you will lose access to these databases and would need to physically travel to a university library to access them. Make the most of your database access during your graduate degree program. We will review in Chapter 4 how to get around paywalls after you graduate.

The databases we described here can be a bit more intimidating, as they have limited natural language support and rely mostly on Boolean searching. However, they contain more advanced search features which can help you narrow down your search to only the most relevant sources, our next step in the research process.

Exercises

- Explore different databases you can access via your university’s library website and searching using your keywords.

- Write notes on which databases and keywords provide you with the most relevant results and the disciplines you are likely to find in each database.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 4: Reduce irrelevant search results

At this point, you should have worked on a few different search queries, swapped in and out different keywords, and explored a few different databases of academic journal articles relevant to your topic. Next, you have to deal with the most common frustration for students: narrowing down your search and reducing the number of results you have to look at. I’m sure at some point you’ve typed a query into Google Scholar or your library’s search engine and seen hundreds of thousands or millions of sources in your search results. Don’t worry! You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research project.

While reading millions of articles is clearly ridiculous, there is no magic number of search results to reach. A good search will return results which are highly relevant. In my experience, student search queries tend to be too general (and have too many irrelevant results), rather than too specific (and have too few relevant results). Don’t worry! You will not need to read all of the articles you find, but reducing the number of results will save you time by eliminating irrelevant articles.

You should have two goals in reducing the number of results:

- Reduce the number of sources until you could reasonably skim through the title and abstract of each source. Generally, you want a hundred or a thousand results, rather than a hundred thousand results.

- Reduce the number of irrelevant sources in your search results until you are much more likely to encounter relevant, rather than irrelevant articles. If only one of every ten results in your search is relevant to your topic for example, you are wasting time. You would be better served by using the tips below to better target your search query.

Here are some tips for reducing the number of irrelevant sources when you search in databases.

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “class size” or “teacher quality.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. A lot of your results may be from articles about irrelevant topics that mention your search term only once. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant. You can be even more restrictive and search for your keywords in the TITLE, but that may be too restrictive, and exclude relevant articles with titles that use slightly different phrasing. Academic databases provide these options in their advanced search tools.

- Use SUBJECT headings to find relevant articles. These tags are added by the organization that provides the database, like the American Psychological Association who curates PyscINFO, to help classify and categorize information for easier browsing.

- Narrow down the years of publication. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful. They no longer tell you the current knowledge on a topic. All databases have options to narrow your results down by year. Check with your professor to see if they have specific guidelines for when an article is “too old.” Note however that seminal articles are likely to be older publications, so make sure to search for both.

- Click the limiters of “full text” and “peer reviewed” to narrow the results (after all, you want to be able to read the full article and they should be from peer reviewed sources.

- Talk to a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know, and they are extensively trained in how to help you!

- Talk to your stakeholders or someone knowledgeable about your target population. They have lived experience with your topic which can help you understand the literature through a different lens. Moreover, the words they use to describe their experiences can also be useful sources of keywords, theories, studies, or jargon.

Exercises

- Using the techniques described in this subsection, reduce the number of irrelevant results in the database queries you have performed so far. Pay particular attention to searching within the abstract, using quotation marks to indicate keyword phrases, and exploring subject headings relevant to your topic.

- Reduce your database query results down to a number (a) where you could reasonably skim through the titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles and (b) where you are much more likely to encounter relevant, rather than irrelevant articles. Repeat this process for your search of each database relevant to your project.

- Write down your queries or save them, so you can recreate them later if you need to return to them. Also, write down any reflections you have on the search process.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search better, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 5: Conduct targeted searches

Another way to save time when searching for literature is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles: review articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reviewing and reading articles they cited in their references. Other types of reviews such as critical reviews may offer a viewpoint along with a birds-eye view of the literature.

Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” or “systematic review” as keywords in your search queries. That said, be careful not to uncritically accept the results reported in these articles–there are ways that meta-analyses can be manipulated.

My advice is to read a review article first, before any type of article. The purpose of review articles is to summarize an entire body of literature is as short an article as possible. This is exactly what students who are learning a new area need. Time is a precious resource for graduate students, and review articles provide the most knowledge in the shortest time. Even if they are a few years old, they should help you understand what else you need to find in your literature search.

As you look through abstracts of articles in your search results, you should begin to notice that certain authors keep appearing. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine.

A similar process can be used for journal names. As you are going through search results, you may also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. You can do so within any database that indexes the journal, like Google Scholar, or through the search feature journal’s webpage. Browse the abstracts and download the full-text PDF of any article you think is relevant.

Step 6: Explore references and citations

The last thing you’ll need to do in order to make sure you didn’t miss anything is to look at the references in each article you cite. If there are articles that seem relevant to you, you may want to download them. Unfortunately, references may contain out-of-date material and cannot be updated after publication. As a result, a reference section for an article published in 2014 will only include references from pre-2014.

To find research published after 2014 on the same topic, you can use Google Scholar’s ‘Cited By’ feature to do a future-looking search. Look up your article on Google Scholar and click the ‘Cited By’ link. The results are a list of all the sources that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar also allows you to search within these articles—check the box below the search bar to do so—and it will search within the ‘Cited By’ articles for your keywords.

Exercises

- Examine the search results from various databases and look for authors and journals that publish often on your topic. Conduct targeted searches of these authors and journals to make sure you are not missing any relevant sources.

- Identify at least one relevant article, preferably a review article. Look in the references for any other sources relevant to your working question. Search for the article in Google Scholar and use the the ‘Cited By’ feature to look for additional sources relevant to your working question.

- Search for review articles that will help you get a broad sense of the literature. Depending on your topic, you may also want to look for other types of articles as well.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

- Write notes on your targeted searches, so you can recreate them later and remember your reflections on the search process.

Getting the right results

I read a lot of literature review drafts that say “this topic has not been studied in detail.” Before you come to that conclusion, make an appointment with a librarian. It is their job to help you find material that is relevant to your academic interests. My first project as a graduate research assistant involved writing a literature review for a professor, and the time I spent working with a librarian on that project brought home how important and impactful they can be. But there is a lot you can do on your own!

Let’s walk through an example. Imagine a local university wherein smoking was recently banned, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers. Students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two. Their activism was surprising. They were advocating for the freedoms of people committing a deviant act—smoking—that is highly disapproved of. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs?

The student researcher began their research by attempting to familiarize themselves with the literature. They started by looking to see if there were any other student smoke-outs using a simple Google search. When they turned to the scholarly literature, their search in Google Scholar for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on their topic, they informed the professor that they would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for them to review. What went wrong here?

The student had been too narrow in their search for articles in their first attempt. They went back to Google Scholar and searched again using queries with different combinations of keywords. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs” they tried, “college student activism,” “smoke-out,” “protest,” and other keywords. This time their search yielded many articles. Of course, they were not all focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but the results addressed their population of interest, college students, and on their broad topic of interest, activism. Experimenting with different keywords across different databases helped them get a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary view of the topic.

Reading articles on college student activism might give them some idea about what other researchers have found in terms of what motivates college students to become involved in activist efforts. They could also play around with their search terms and look for research on activism centered on other sorts of activities that are perceived by some to be deviant, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, they needed to broaden their search about college student activism to include more than just smoke-outs and understand the theory and empirical evidence around student activism.

Once they searched for literature about student activism, they could link it to their specific research focus: smoke-outs organized by college student activists. What is true about activism broadly is not necessarily true of smoke-outs, as advocacy for smokers is unique from advocacy on other topics like environmental conservation. Engaging with the sociological literature about their target population, college students who smoke cigarettes, for example, helped to link the broader literature on advocacy to their specific topic area.

Revise your working question often

Throughout the process of creating and refining search queries, it is important to revisit your working question. In this example, trying to understand how and why the smoke-out took place is a good start to a working question, but it will likely need to be developed further to be more specific and concrete. Perhaps the researcher wants to understand how the protest was organized using social media and how social media impacts how students perceived the protests when they happened. This is a more specific question than “how and why did the smoke-out take place?” though you can see how the researcher started with a broad question and made it more specific by identifying one aspect of the topic to investigate in detail. You should find your working question shifting as you learn more about your topic and read more of the literature. This is an important sign that you are critically engaging with the literature and making progress. Though it can often feel like you are going in circles, there is no shortcut to figuring out what you need to know to study what you want to study.

Key Takeaways

- The quality of your search query determines the quality of your search results. If you don’t work on your queries, you’ll get a million results, only a small percentage of which are relevant to your project.

- Keywords and queries should be updated as you learn more about your topic.

- Your two goals in targeting your database searches should be reducing the number of results for each search query to a number you can feasibly skim and making those results more relevant to your project.

- Techniques to increase the number of relevant results in a search include using Boolean operators, quotation marks, searching in the abstract or title, and using subject headings.

- Use the databases that are most relevant to your topic. For general searches, Google Scholar has some strengths (ease of use, Cited By) and limitations (cannot search in abstract, includes resources other than journal articles). You can access other databases through your university’s library.

- Don’t be afraid to reach out to a librarian or your professor for help with searching. It is their job to help you.

Exercises

- Reflect on your working question. Consider changes that would make it clearer and more specific based on the literature you have skimmed during your search.

- Describe how your search queries (across different databases) address your working question and provide a comprehensive view of the topic.

- The Guardian (n.d.). The counted: People killed by police in the US. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database ↵ ↵

- Kelly, J., Sadeghieh, T., & Adeli, K. (2014). Peer review in scientific publications: Benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. EJIFCC, 25(3), 227–243. ↵

- Ades, R. (2020, February 20). An end to "blind review." Blog of the APA. https://blog.apaonline.org/2020/02/20/an-end-to-blind-review/ ↵

- Berger, M., & Cirasella, J. (2015). Beyond Beall’s list: Better understanding predatory publishers. College & research libraries news, 76(3), 132-135. ↵

- Brainard, J. (2019, October 10). In bid to boost transparency, bioRxiv begins posting peer reviews next to preprints. Science magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/10/bid-boost-transparency-biorxiv-begins-posting-peer-reviews-next-preprints ↵

- Houser, J., (2018). Nursing research reading, using, and creating evidence (4th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett. ↵

- Keith Walker & Benjamin Kutsyuruba (2019). The Role of School Administrators in Providing EarlyCareer Teachers’ Support: A Pan-Canadian Perspective. International Journal of Education Policy &Leadership 14(2). URL: http://journals.sfu.ca/ijepl/index.php/ijepl/article/view/862 doi: 10.22230/ijepl.2019v14n2a862.IJEPL ↵

- Kelly, M. S., Kubert, P., & Freed, H. (2020). Teen depression, stories of hope and health: A promising universal school climate intervention for middle school youth. International Journal of School Social Work, 5(1), 3. ↵

- Reynolds, A. D., & Bacon, R. (2018). Interventions supporting the social integration of refugee children and youth in school communities: A review of the literature. Advances in social work, 18(3), 745-766. ↵

- Uman, L. S. (2011). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(1), 57-59 ↵

- Laitsch, D., Nguyen, H., & Younghusband, C. (2021). Class size and teacher work: Research provided to the BCTF in their struggle to negotiate teacher working conditions. Canadian Journal for Educational Administration & Policy, 196, 83-101. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/ index.php/cjeap/article/view/70670 ↵

- Graham, S., Liu, X., Aitken, A., Ng, C., Bartlett, B., Harris, K. R., & Holzapfel, J. (2018). Effectiveness of Literacy Programs Balancing Reading and Writing Instruction: A Meta-Analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 53(3), 279–304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26622547 ↵

- Michelle Pidgeon & Tasha Riely. (2021). Understanding the Application and Use of Indigenous Research Methodologies in the Social Sciences by Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Scholars. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership 17(8). URL: http://journals.sfu.ca/ijepl/index.php /ijepl/article/view/1065 doi:10.22230/ijepl.2021v17n8a1065IJEPL. ↵

- Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2020) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61 ,101860. ↵

- Ann Kajander, Matt Valley, Kelly Sedor, & Taylor Murie. (2021). Curriculum for Resiliency: Supporting a Diverse Range of Students’ Needs in Grade 9 Mathematics. Canadian Journal of Action Research 22(1). pp. 69-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v22i1.547. ↵

- Montgomery, L., Hartley, J., Nevlon, C., Gillies, M., Gray, E., Herrmann-Pillath, C., Huana, C., Leach, J., Potts, J., Ren, X., Skinner, K., Sugimoto, C., & Wilson, K. (2021). Change. In Open knowledge institutions: Reinventing universities. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13614.001.0001 ↵

- Writing for Success (2015). Strategies for gathering reliable information. http://open.lib.umn.edu/writingforsuccess/chapter/11-4-strategies-for-gathering-reliable-information/ ↵

published works that document a scholarly conversation on a specific topic within and between disciplines

an academic field, like social work

trade publications, magazines, and newspapers

in a literature review, a source that describes primary data collected and analyzed by the author, rather than only reviewing what other researchers have found

interpret, discuss, and summarize primary sources

periodicals directed to members of a specific profession which often include information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field

a formal process in which other esteemed researchers and experts ensure your work meets the standards and expectations of the professional field

a classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge” (Houser, 2018, p. 112)

report the results of a quantitative or qualitative data analysis conducted by the author

unprocessed data that researchers can analyze using quantitative and qualitative methods (e.g., responses to a survey or interview transcripts)

journal articles that summarize the findings other researchers and establish the state of the literature in a given topic area

journal articles that identify, appraise, and synthesize all relevant studies on a particular topic (Uman, 2011, p.57)

a study that combines raw data from multiple quantitative studies and analyzes the pooled data using statistics

a study that combines primary data from multiple qualitative sources and analyzes the pooled data

discuss a theory, conceptual model, or framework for understanding a problem

describe “how things are done” or comment on pressing issues in practice (Wallace & Wray, 2016, p. 20)

review primary and secondary sources

research reports released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think-tanks

search terms used in a database to find sources of information, like articles or webpages

the words or phrases in your search query

a searchable collection of information

when a publisher prevents access to reading content unless the user pays money