22

Chapter Outline

- Case study (12 minute read)

- Constructivist (9 minute read)

- Oral history (10 minute read)

- Ethnography (8 minute read)

- Phenomenology (9 minute read)

- Narrative (9 minute read)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to research as a bullying, housing insecurity, suicide, environmental oppression, race and access to leadership, older adult residential care, LGBTQ+ rights, immigration experiences, the lived experience of being a Person of Color in the United States, case management, discrimination, having a chronic disease or condition, HIV, religion, and sex work.

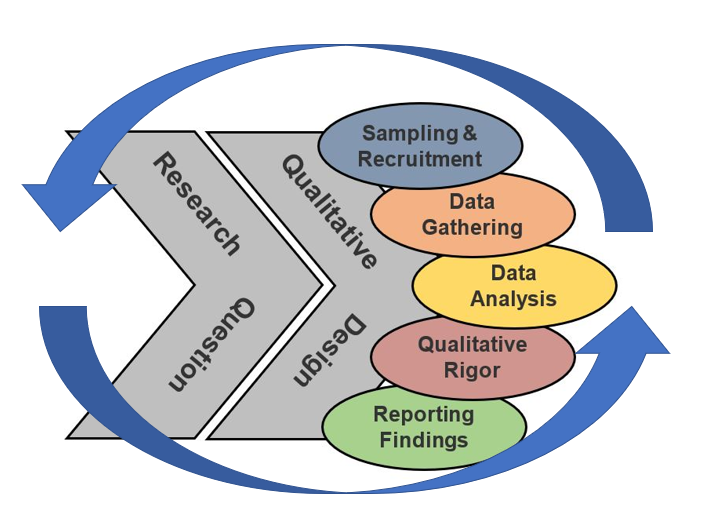

Qualitative inquiry reflects a rich diversity of approaches with which we can explore the world. These approaches originate from philosophical and theoretical traditions that offer different strategies for us to systematically examine social issues. The placement of this chapter presented challenges for us. In many respects, your choice of design type is central to your research study, and might very well be one of the first choices you make. Based on this, we had considered leading off our qualitative section with this chapter, thereby exposing you to a range of different types of designs. Obviously, we had second thoughts. We ended up putting it at the end because we realized that if we opened up with this part of the discussion, you really wouldn’t have the background information to help you make sense of some of the differences between the various designs. Throughout our exploration of qualitative design thus far, we have discussed a number of decision points for you to consider as you design your study. Each of these decisions ties into your research question and ultimately will also be informed by, and help to inform, your research design choice. Your design choice truly reflects how these design elements are being brought together to respond to your research question and tell the story of your findings.

As we discussed in Chapter 19, qualitative research tends to flow in an iterative vein, suggesting that we are often engaged in a cyclical process. This is true in the design phase of your study as well. You may revisit preliminary plans and decide that you now want to make changes to more effectively address the way in which you understand your research question or to improve the quality of your overall design. Don’t beat yourself up for this, this is part of the creative process of research! There is no perfect design and you are much better served by being a dynamic and critical thinker during the design process, rather than rigidly adhering to the first idea that comes along. We will now explore six different qualitative designs. Each will just be a brief introduction to that particular type of research, including what the main purpose of that design is and some basic information about conducting research in that vein. If you are interested in creating a proposal using a particular design, a number of resources and example studies are provided for each category.

Exercises

Below is a brief checklist and justification questions to help you think about consistency across your qualitative design. When you have finished this chapter, come back to this exercise and see if you can complete this as it applies to your proposal.

- Is my research question a good fit for a qualitative approach?

- If yes, explain why this is:

- If no, consider a quantitative approach, or revising your research question so it is a better fit.

- Is my research question a good fit for the specific qualitative research design I have chosen?

- If yes, explain why this is:

- If no, explain why not, and what approach you might consider as an alternative:

- If you’re not yet sure about which design you might choose, review the ones discussed in this chapter and consider what the value/purpose of each of them is. Which one seems like the best match for your question? (if you still aren’t sure, it might be good to consult with your professor)

22.1 Case study

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with case study design

- Determine when a case study design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of case study research?

We’ve already covered that qualitative research is often about developing a deep understanding of a topic from a relatively small sample, rather than a broader understanding from the many. This is especially true for case study research. Case studies are essentially a ‘deep dive’ into a very focused topic. Skeptics of qualitative research often discount the value in studying the experiences and understandings of individuals and small groups, arguing that this type of research produces little value because it doesn’t necessarily apply to a large number of people (i.e. produce generalizable findings). Hopefully you recognize the positivist argument here. These folks are likely to be unimpressed with the narrow focus that a case study adopts, suggesting that the restricted purview of a case study has little value to the scientific community. However, interpretativist qualitative researchers would counter that by thoroughly studying people, interactions, events, and the context in which they occur, researchers uncover key information about human beings, social interactions, and the nature of society itself. Remember, from this interpretative philosophical orientation we are not looking for what is “true” for the many, but we are seeking to recognize and better understand the complexity of life and human experiences; the multiple truths of a few. Case studies can be excellent for this!

Part of the allure of case studies stem from their diversity. You might choose to study:

- Individuals, such as a student with a unique need or a teacher with a unique position

- Small Groups, such as a newly formed anti-bullying student task force at a school

- Population (usually relatively small), such as the residents of a community that are losing their school because of low enrolment

- Events, such as a fire at a school

- Process, such as a community organizing entity trying to create a five day hot meal program in a local school

If we choose to utilize a case study design for our research, the use of theory can be incredibly helpful to guide and support our purpose throughout the research process. The Writing Center at Colorado State University offers a very helpful web resource for all aspects of case study development, and one page is specifically dedicated to theoretical application for case study development. They outline three general categories of theory: individual theories, organizational theories, and social theories, all of which case study researchers might draw from. These are especially helpful for us as education researchers, who may focus on research across micro, mezzo, and macro environments (as evidenced in the aforementioned case study examples). For instance, if you are the researcher in the last example, looking at community members creating a local ordinance, you might draw on Community Organizing Theory and Capabilities Perspective to structure your study. As an alternative, if you are studying the experience of the first Black woman board president of a local school board, you might borrow from Minority Stress and Strengths Perspective as models as you develop your inquiry. Whatever your focus, theory can be an important tool to aid in orienting and directing your work.

What is involved with case study research?

Due to the diversity of topics studied and types of case study design, no two case studies look alike (just like snowflakes). For this reason, I’m going to focus this section on some common hallmarks of case studies that will hopefully help you as you think about designing and consuming case study research.

As the name implies, our emphasis with case study research is to provide an understanding of a specific case. The range of what qualifies as a case is extensive, but regardless, we are primarily aiming to explore and describe what is going on in the given case we are studying. As case study researchers, this means we need to work hard to gather rich details. We aren’t satisfied with surface, generic overviews or summaries, as these won’t provide the multidimensional understanding we are hoping for. Thinking back to our chapter on qualitative rigor, a case study researcher might aim to produce a thick description with the details they gather as a sign of rigor in their work. To gather these details, we need to be open to subtleties and nuances about our topic. If we are expending the energy to study a case in this level of detail, the research assumptions are that the case could provide valuable information and that we currently know relatively little about this case. As such, we don’t want to assume that we know what we are looking for. This means that we need to build in ways to capture unanticipated data and check our own assumptions as we design and conduct our study. We might use tools like reflexive journaling and peer debriefing to support rigor in this area.

Another good way to demonstrate both rigor and cultural humility when using this approach is engage stakeholders actively throughout the research process who are intimately involved with the case. This demonstrates good research practice in at least two ways. It potentially helps you to gather relevant and more meaningful data about the case, as a person who is connected to the case will likely know what to look for and where. Secondly, and more importantly, it reflects transparency and respect for the subjects of the case you are studying.

Another key feature of most case studies is that they don’t rely on one source of data. Again, returning to our exploration of qualitative rigor, triangulation is a very important concept for case study research. Because our target is relatively narrow in case study design, we often try to approach understanding it from many different angles. As a metaphor, you might think of developing a 360° view of your case. What level of dimensionality can you introduce by looking at different types of data or different perspectives on the issue you are studying? While other types of qualitative research may rely solely on data collected from one method, such as interviews, case studies traditionally require multiple. So, in the example above where you are studying the residents of a community that is losing its school, you might decide to gather data by:

- Conducting interviews with residents

- Making observations in the school

- Attending community meetings

- Conducting key informant interviews with businesses, educators, human service providers, librarians, historians, and local politicians who serve the area

- Examining correspondence that community members share with you about the impending changes

- Examining media coverage about the impending changes

Furthermore, if you are invested in engaging stakeholders as discussed above, you might form a resident advisory group that would help to oversee the research process in its entirety. Ideally this group would have input into how results are shared and what they would hope to gain as a result of the study (i.e. what kind of change would they like to see come from this).

Case studies can often draw out the creativity in us as we consider the range of sources we may want to tap for data on our case. Of course, this creativity comes at a price, in that we invite the challenge of designing research protocols for all these different methods of data collection and address them thoroughly in our IRB applications! Finally, with the level of detail and variety of data sources we have already discussed, case studies endeavor to pay attention to and provide a good accounting of context. If we are working to provide a rich, thick description of our case, we need to offer our audience information about the context in which our case exists. This can mean that we collect data on a range of things that might include:

- the socio-polticial environment surrounding our case

- the background or historical information that preceded our case

- the demographic information that helps to describe the local community that our case exists in

As you consider what contextual information you plan to gather and share, stay fluid. Again, it is likely that we won’t know in advance the many contextual features that are reflected in our case. If you are doing a good job listening to your participants and engaging stakeholder in your process, they will tell you what is important to note. As social workers, we draw on a person-in-environment approach to help us conceptualize the ways in which our clients interact with the world around them and the challenges they encounter. Similarly, as researchers, we want to conceptualize case study-in-environment as we are developing our case study projects.

Key Takeaways

- Case studies offer an effective qualitative design when seeking to describe or understand a very specific phenomenon in great detail. The focus of a “case” can cover a range of different topics, including a person, a group, an event or a process.

- The design of a case study usually involves capturing multiple sources of data to help generate a rich understanding of both the content and the context of the case.

Exercises

Based on your social work passions and interests:

- What is a specific topic you feel might be well-suited for a case study?

- What potential sources of data would you use for your case study?

- What sorts of contextual information would you want to make sure to search for to get a really comprehensive understanding of your case?

Resources

To learn more about case study research

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers.

Gibbs, G.R. (2012, October, 24). Types of case studies: Part 1 of 3 on case studies.

Gibbs, G.R. (2012, October, 24). Planning a case study: Part 2 of 3 on case studies.

Gibbs, G.R. (2012, October, 24). Replication or single cases: Part 3 of 3 on case studies.

Harrison et al. (2017). Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations.

Hyett et al. (2014). Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports.

Lock, I., & Seele, P. (2018). Gauging the rigor of qualitative case studies in comparative lobbying research. A framework and guideline for research and analysis.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Starman, A. B. (2013). The case study as a type of qualitative research.

Writing@CSU, the Writing Studio: Colorado State University (n.d.). Case studies.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

For examples of case study research

Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2017). The utilization of social media for youth outreach engagement: A case study.

Gabriel, M. G. (2019). Christian faith in the immigration and acculturation experiences of Filipino American youth.

Paddock et al. (2018). Care home life and identity: A qualitative case study.

22.2 Constructivist

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with constructivist design

- Determine when a constructivist design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of constructivist research?

Constructivist research seeks to develop a deep understanding of the meaning that people attach to events, experiences, or phenomena. It draws heavily from the idea that our realities are constructed through shared social interaction, within which each person holds a unique perspective that is anchored in their own position (where they are situated in the world) and their evolving life experiences to date. Constructivist research then seeks to bring together unique individual perspectives around a common topic or idea (the basis of the research question), to determine what a shared understanding for this particular group of participants might be. By developing a common or shared understanding, we are better able to appreciate the multiple sides or facets of any given topic, helping us to better appreciate the richness of the world around us. You can think about constructivist research as being akin to cultural humility. When we approach practice with a sense of cultural humility, we assume that people who participate in a shared culture experience it from their own unique perspective. As we work with them, we try our best to understand and respect their personal understanding of that culture. Similarly, in constructivist research, we attempt to bring together (and honor) these unique individual perspectives on a given topic and construct a shared understanding, attempting to take what might be one-dimensional and making it multidimensional.

Constructivist research, as a method of inquiry, originated out of the work of Lincoln and Guba (1985),[1] although it was initially termed “naturalism”. In stark contrast to more positivist research traditions that make the assumption that the broad aim of research as an approach to knowledge building is to produce generalizable findings, constructivist research assumes that any knowledge produced through the research process is context-dependent. This means that constructivist findings are specific to those who contributed to that knowledge building and the situation in which it took place. That isn’t to say that these results might not have broader value or application, but the aim of the constructivist researcher is not to make that claim. The aim of the constructivist design is to provide a rich, full, detailed account of both the research process and the research findings. This inlcudes a detailed description of the context in which the research is taking place. In this way, the research consumer can determine the value and application of the research findings. The video by Robertson (2007)[2] in the resources box offers a good overview of this methodology and many of the assumptions that underlie this approach.

If you are a researcher considering a constructivist design, Rodwell (1998)[3] suggests that you should consider the focus, fit, and feasibility of your study for this particular methodology. While she provides a very helpful discussion across all three areas, her attention to ‘fit’ for constructivist inquiry is perhaps most relevant for our abbreviated overview of this methodology. In her discussion of ‘fit’, Rodwell argues that research questions well-suited for constructivist research are:

- Multi-dimensional: meaning that multiple constructions or understandings of the “reality” of the topic are being sought

- Investigator interactive: meaning that the topic is susceptible to researcher influence by virtue of the researcher having to be very involved in data collection and therefore accountable for considering their role in the knowledge production process

- Context-dependent: meaning that the circumstances surrounding the participants and the research process must be taken into account

- Complex: meaning we should assume there are multiple causes that contribute to the problem under investigation (and that the research is seeking to explore, rather than collapse that complexity)

- Value-laden: meaning that the topic we are studying is best understood in a way that accounts for the diverse values and opinions people attach to it.

What is involved with constructivist research?

As you may have surmised from the discussion above, the cornerstone of constructivist research is the researcher engaging in immersive exchanges with participants in an effort to ‘construct’ the meaning that they attach to the topic being studied.

Again, drawing on Rodwell’s (1998) [4] description of this methodology, a constructivist researcher needs to recruit a [pb_glossaryid=”918″]purposive[/pb_glossary] sample that has unique and diverse first-hand knowledge of the topic being studied. They will gather data from this sample regarding their respective realities or understandings of the topic. They will attempt to account for the context in which the study is taking place (including the researcher’s own influence as a human instrument). Throughout the analysis process they will work towards producing negotiated outcomes, taking time to clarify and verify that findings accurately capture the sentiment of participants; treating participants as experts in their own reality. Finally, they will bring this knowledge together in a way that attempts to reflect the complex and multidimensional understandings of the topic being studied.

Constructivist research findings are well-suited for being presented as a case report. This allows for many realities or understandings of a given topic to be constructed. When you think about the value of constructivist research for education, review some of the research articles listed below as examples. Envision using the findings from Oberg’s (2019)[5] study about barriers to leadership learning to help build leadership capacity at SFU. Also, as a principal in a high school, you could use Philander’s (2021)[6] work focused on communities of practice in school to help inform ongoing staff development efforts.

Key Takeaways

- Constructivist studies are well suited to develop a rich, multidimensional understanding of a topic through the extensive study of the experience of that topic across multiple observers. The individual realities experienced by participants are brought together to developed a shared, constructed understanding.

- The end result of a constructivist research project should help the consumer to see the phenomenon being studied from many different perspectives and with an appreciation of its complexity and nuance.

Resources

To learn more about constructivist research

Drisko, J. W. (2013). Constructivist research in social work. In A. E. Fortune, W. J. Reid, & R. L. Miller, Jr. (Eds.), Qualitative research in social work (2nd ed.), (pp. 81-106). New York : Columbia University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2013). The constructivist credo. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

Mojtahed et al. (2014). Equipping the constructivist researcher: The combined use of semi-structured interviews and decision-making maps.

Robertson, I. (2007, May 13). Naturalistic or constructivist inquiry.

Rodwell, M. K. (1998). Social work constructivist research. New York: Routledge

Stewart, D. L. (2010). Researcher as instrument: Understanding” shifting” findings in constructivist research.

For examples of constructivist research

Allen, M. (2011). Violence and voice: Using a feminist constructivist grounded theory to explore women’s resistance to abuse.

Coleman et al. (2012). A constructivist study of trust in the news.

Cook, G., & Brown-Wilson, C. (2010). Care home residents’ experiences of social relationships with staff.

Leichtentritt et al. (2011). Construction of court petitions in cases of alternative placement of children at risk: Meaning‐making strategies that social workers use to shape court decisions.

O’Callaghan et al. (2012). Music’s relevance for adolescents and young adults with cancer: A constructivist research approach.

22.3 Oral history

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with oral history design

- Determine when an oral history design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of oral history research?

As outlined by the Oral History Association (OHA, 2009), “Oral history interviews seek an in-depth account of personal experience and reflections, with sufficient time allowed for the narrators (interviewees) to give their story the fullness they desire. The content of oral history interviews is grounded in reflections on the past as opposed to commentary on purely contemporary events”.[7] Much like case studies with their intentionally narrow focus, oral histories are dedicated to developing a deep understanding with a relatively limited scope. This may include a single oral history provided by one interviewee, or a series of oral histories that are offered around a unifying topic, event, experience or shared characteristic.

Now, what makes this a form of research and not just a venue for sharing stories (valuable in-and-of-itself), is that these stories are connected systematically and there is a central question or series of questions that we as researchers are attempting to answer. For instance, the Columbia Center for Oral History Research at Incite hosts the Human Rights Campaign Oral History Project. This project seeks to understand: “What can a single organization tell us about a social movement and social change? How do historic moments shape organizations and vice versa? How do institutions with diverse constituencies reconcile competing needs and agendas for a forward-thinking movement, all while effectively responding to consistent external attacks?”[8] By interviewing people connected with this organization and its work, this oral history project is simultaneously hoping to gain a rich understanding of the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), but also an appreciation of how social change may occur more broadly, with HRC as an instructive example.

Particularity relevant for education research, oral histories are often used for the purpose of studying and promoting social change, as in the HRC example. For instance, Groundswell is a network of “oral historians, activists, cultural workers, community organizers, and documentary artists” dedicated to the use of oral history as a tool for social change.[9] The central idea here is that by sharing our stories, we can learn from each other. Much like in other narrative traditions, our stories contain valuable and transformative information. In the case of oral histories, the hope is that these shared narratives are transformative for the audience by offering new perspectives on the world, what it needs, and what it offers. Ideally this transformation leads to action and broader social change.

What is involved in oral history research?

While the core of oral history research involves interviewing people to capture their historical accounts to help explore a broader question or set of questions, the research process is a bit more involved than this. Moyer (1999)[10] offers an overview of the steps involved in conducting oral history research.

- Formulate a central question, set of questions, or issue

- Plan the project. Consider such things as end products, budget, publicity, evaluation, personnel, equipment, and time frames.

- Conduct background research

- Interview

- Process interviews

- Evaluate research and interviews and cycle back to step 1 if the central question is not sufficiently answered, or go on to step 7 if it is

- Organize and present results

- Store materials archivally

Of course, these are generic steps and only a beginning introduction to oral history design. Each of these steps has its own learning curve and nuance. For instance, interviewing for oral histories can vary in both preparation and application when compared to interviewing for other forms of qualitative research. Resources for further learning on oral history research are offered at the end of this section to help you become more knowledgeable and proficient. In addition to this overview of the design process, there are a number of unique principles associated with conducting oral histories. Let’s discuss a few of these.

Oral history as a relationship between the interviewer and interviewee

Just as with other forms of interviewing, the expectation is the participation is voluntary and only proceeds after informed consent is provided. While this is very important for all research, it is perhaps especially important for oral histories because of some of the aspects discussed below (e.g. public access, frequent disclosure of identifying information) that differentiate oral histories.[11][12] Thoroughly explaining what oral histories are, how they are conducted, and the nature of the research final products is especially important. In addition, interviewees for oral histories often have a greater degree of control in their storytelling, with less direction from the interviewer (compared with other forms of qualitative interviewing).[13][14] This potentially challenges some of the power dynamics in more traditional research traditions. While the interviewer does provide the initial prompt or question and hopes to obtain an in-depth account, the interviewee is largely in control of how the story is told.

Oral history as a research product

Consistent with our code of ethics and the expectations of all qualitative researchers, interviewees should be treated with dignity and respect. For the purposes of oral history research, this is in part demonstrated through crafting significant historical questions and engaging in prior research and preparation to inform the study (generally) and the interview (specifically).[15][16]. This will lay the foundation for a well-informed oral history project. The oral history is a detailed historical recounting by one person or a small group of people. It is meant to be a ‘window in time’ through the lens of the interviewee.[17] Because an oral history involves the detailed telling of personal stories and experiences it is often expected that the finished products of oral histories will often provide identifying information; it is often unavoidable in recounting the history. In fact, the interviewee is typically identified by name due to the extensive detail and contextually identifying information that is gathered.[18][19] Again, this should be made abundantly clear during the recruitment process and spelled out in the informed consent.

Oral history as an ongoing commitment

Traditional research is often shared with the public through journal articles or conference proceedings, and these often do not provide access to the data. While oral history research may be shared in these venues, the expectation is generally that oral history interviews that are collected will also be made accessible to future researchers and the public.[20] To accommodate this, researchers need to be planful in how they will provide this access in a sustainable way. This also means they need to have access to and operating knowledge of technology that will allow for quality audio capture and maintenance of these oral histories.[21][22] Furthermore, this obligation needs to be very clear to participants before they share their hisitories. Also, because of the level of access that is often afforded to oral history interviews, researchers can’t guarantee how others may use or portray these interviews in the future and should be mindful not to overpromise such guarantees to participants.

Cultural considerations with storytelling

I think it is also important for us to consider the cultural implications of storytelling and the connection this holds for oral history research. Many cultural groups have and continue to depend on storytelling as a means of transmitting culture through time and space. Lately, I have been thinking about this as a response to the racial conflict we have been experiencing in the United States. It can be particularly powerful to hear the stories of others and to allow ourselves to be changed by them. The author Ta-Nehisi Coates book Between the World and Me is a profound nonfiction work that is written as a letter to his teenage son about what it means to be a Black man in America, drawing on his own memories, experiences and observations. In addition, Takunda Muzondiwa, offers a beautifully articulated performance of spoken word poetry about her history as a young woman immigrating from Zimbabwe to New Zealand. I believe these stories can be powerful antidotes to the fear and ignorance that fuels so much of the structural oppression and racial division in this country. Gathering oral histories can help contribute to elevating these voices and hopefully promoting understanding. However, I think we also have to be very aware of the danger in this practice of cultural appropriation. It requires us to be extremely vigilant in how these stories are obtained and presented, and who has ownership of them.

Key Takeaways

- Oral histories offer a unique qualitative research design that support an individual or group of participants reflecting on a unique experience, event, series of events, or even a lifetime. While they explicitly explore the past, they often do so to learn about how change occurs and what lessons can be applied to our present.

- While many aspects of oral histories are consistent with other forms of qualitative research (e.g. the use of interviews to collect data, analyzing narrative data for themes), oral histories have some defining features that differentiate it from other designs, such as a common expectation for public access to collected data.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

For me, oral history has a bit of a different feel when compared to other qualitative designs because it really highlights intimate details of one person’s (or a small group) life. in a way that makes confidentiality a real challenge in many cases (or even impossible). That being said, I’m also really drawn to the potential of this approach for allowing people to share wisdom and for us to learn from each other.

Based on what you have read here and maybe after checking out some of the resources below, what are your thoughts about using oral histories?

- What do you see as strengths?

- What are barriers or challenges that you foresee?

- What oral history data might help to strengthen or develop your practice knowledge? (whose wisdom and historical perspective might you learn from)

Resources

To learn more about oral histories and oral history archives

Columbia University, Interdisciplinary Center for Innovative Theory and Empirics (n.d.) Columbia Center for Oral History Research at INCITE.

Groundswell. (2014). Groundswell: Oral history for social change.

Institute for Museum and Library Services. (n.d.). Oral history in the digital age.

International Oral History Association. (n.d.). International Oral History Association, homepage.

Moyer, J. (1999). Step-by-step guide to oral history.

Oral History Association (2009, October). Principles and best practices.

UCLA (2015). UCLA Center for Oral History Research.

For examples of oral history research

Gardella, L. G. (2018). Social work and hospitality: An oral history of Edith Stolzenberg.

Wuenstel, M. (2002). Participants in the Arthurdale Community Schools’ experiment in progressive education from the years 1934-1938 recount their experiences. Education, 122(4), 759–769.

Jenkins, S. B. (2017). “We were all kind of learning together” The emergence of LGBTQ+ affirmative psychotherapy & social services, 1960-1987: oral history study.

Johnston et al. (2018). The rise, fall and re-establishment of Trinity Health Services: Oral history of a student-run clinic based at an inner-city Catholic Church.

La Rose, T. (2019). Rediscovering social work leaders through YouTube as archive: The CASW oral history project 1983/1984.

22.4 Ethnography

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Distinguish between key features associated with ethnographic design

- Determine when an ethnographic design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of ethnography research?

Ethnography is a qualitative research design that is used when we are attempting to learn about a culture by observing people in their natural environment. While many immediately associate culture with ethnicity, remember that cultures are all around us, and we exist in many simultaneously. For example, you might have a culture within your family, at your school, at work, as part of other organizations or groups that you belong to. Culture exists where we have a social grouping that creates shared understanding, meaning, customs, artifacts, rituals, and processes.

Cultural groups can exist in-person and in virtual spaces. Culture challenges us to consider how people understand and dynamically interact with their environment. Creswell (2013) outlines the role of the ethnographer as, “describing and interpreting the shared and learned patterns of values, behaviors, beliefs and languages of culture-sharing groups” (p.90).[23] Below is a brief list of areas where we may find “culture-sharing groups”.

- Work

- School

- Home

- Peer Groups

- Support Groups

- Cause-Related Groups

- Organizations

- Interest-Related Groups

Exercises

Respond to the following questions.

- What cultures do you participate in?

- What cultures might the clients you work with in your field placements participate in?

- What cultures might the participants you are interested in studying participate in?

Reflecting on this question can help us to see ourselves and our clients or our research participants as multidimensional people and to develop solid research proposals.

Now that we have discussed what culture is, why is it important that we research it? More specifically, why is it important that we have ethnography, a type of qualitative research dedicated to studying culture? As practitioners and educators, we talk extensively about concepts like cultural competence and cultural humility. As a profession, we have taken the position that understanding culture is vital to what we do. Ideologically, education recognizes that people have very different experiences throughout their lives. Some of these experiences are shared and can come to shape the perspective of groups of people, and in turn, how these groups interact with the world around them and with each other. By studying these shared perspectives, ethnographers hope to learn both how groups of people are shaped by and come to shape their environment (this is the definition of a fancy term, reciprocal determinism). Ethnographic research can be one source of information that helps support culturally informed teaching practice. Note that I specifically said one source. As an ethnographer, we are typically an “outsider” observing and learning about a culture. As practitioners, we should also be educated about culture directly from our students because they have “insider” knowledge. Both are valuable and can be helpful for the work we do, but I would argue that we give priority to our students’ perspectives, as they are an authority on their experience of culture.

As you think about the value of ethnographic research, it can also be helpful to think about what types of things we might learn from it. Let’s take a specific example. What if we wanted to study the culture around a student study group. What are some of the things we might hope to learn by examining the culture of this group?

- What motivates them to participate in the group?

- What are their expectations about the group?

- What do they hope to get out of the group?

- What are the group norms?

- What are the formal and informal roles of the group?

- What functions does the group serve?

- What types of group dynamics are evident?

- What influence external to the group impact the group, and how?

What is involved with ethnography research?

As a process of uncovering and making sense of a culture, ethnographic research involves the researcher immersing themselves in the culture to gain direct and indirect information through keen observation, discussion with culture-sharing members, and review of cultural artifacts. To accomplish this successfully, the ethnographer will need to spend extensive time in the field, both to gather enough data to comprehensively describe the culture, and to gain a reasonable understanding of the context in which the culture takes place so that they can interpret the data as accurately as possible. Hammersley (1990)[24] outlines some general guidelines for conducting ethnographic research.

- Data is drawn from a range of sources

- While data gathering is systematic, it is emergent and begins with a loose structure

- Parameters are usually placed on the setting(s) from which data is gathered

- Observing behavior in everyday life

- Analysis involves the interpretation of human behavior and making sense out of the actions of the culture group

Below I provide some additional details around each of these principles to help contextualize how these might compare and contrast with other qualitative designs we have been discussing.

Data is drawn from a range of sources

Since our objective is to understand a culture as comprehensively as possible, ethnographies require multiple sources of data. If someone wanted to study the culture within your leadership program, what sorts of data might they utilize? They might include discussions with students, staff, and faculty; observations of classes, functions, and meetings; review of documents like mission statements, annual reports, and course evaluations. These are only a small sampling of data sources that you might include to gain the most holistic understanding of the program.

While data gathering is systematic, it is emergent and begins with a loose structure

While some qualitative studies begin with an extensive and detailed plan for data gathering, ethnographies begin with a considerable amount of flexibility. This is because we often don’t know in advance what will be important in developing an understanding of a culture and where that information might come from. As such, we would need to spend time in the culture, being attentive and open to learning from the context.

Parameters are usually placed on the setting(s) from which data is gathered

Culture can extend across space and time, making it overwhelming as we initially consider how to focus our efforts while still allowing for the emergent design discussed above. Because of this, ethnographies are often confined to one particular setting or group. I don’t know if any of you are fans of the TV series The Office (either the British or American versions), but it actually offers us a good example here. The series is based on following the antics that take place in an office environment with a group of co-workers through a mockumentary . The series is about understanding the culture of that office. The majority of filming takes place in a small office and with a relatively small group of people. These parameters help to define the storyline, or for our purposes, the scope of our data gathering.

Observing behavior in everyday life

Compared to other qualitative approaches where data gathering may take place through a more formal process (e.g. scheduled interviews, routine observations of specified exchange), ethnographies usually involve collecting data in everyday life. To capture an authentic representation of culture, we need to see it in action. Thus, we need to be prepared to gather data about culture as it is being produced and experienced.

Analysis involves the interpretation of human behavior and making sense out of the actions of the culture group

Related to the last point about observing behavior in everyday life, culture is created and transmitted through social interactions. As ethnographers, the main thrust of our work is to observe and interpret how people engage with each other, and what these interactions mean.

Cultural considerations with storytelling

As I mentioned in the oral history section, I think we also need to be really attentive to the possibility of cultural appropriation and exploitation when conducting ethnographies. This is really true for all types of research, but it deserves special attention here because of the duration of time ethnography requires immersing yourself in the culture you are studying. As an ethnographer, you are attempting to enter into the very personal space of that cultural group. Before doing so, as researchers, I think we need to very carefully consider what benefits does this study offer. If the only answer is that we benefit professionally or academically, then is it really worth it for us to be so intrusive? Of course, actively including community members in the research process and allowing them to help determine the benefits they hope to recognize from such a study can be a good way to overcome this.

Key Takeaways

- Ethnographic studies allow researchers to experience and describe a culture by immersing themselves within a culture-sharing group.

- Ethnographic research requires that researchers be attentive observers and curious explorers as they spend extensive time in the field viewing cultural rituals and artifacts, speaking with cultural group members, and participating in cultural practices. This requires spending extensive time with this group to understand the nuances and intricacies of cultural phenomenon.

Resources

To learn more about ethnography research

Genzuk, M. (2003). A synthesis of ethnographic research.

Isaacs, E., TEDxBroadway. (2013, January, 28). “Ethnography”—Ellen Isaacs.

Wall, S. (2015, January). Focused ethnography: A methodological adaptation for social research in emerging contexts.

Reeves et al. (2013). Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80.

Sangasubana, N. (2011). How to conduct ethnographic research.

For examples of ethnography research

Kozol. (1991). Savage inequalities : children in America’s schools / Jonathan Kozol. Crown Pub.

Avby et al. (2017). Knowledge use and learning in everyday social work practice: A study in child investigation work.

Hicks, S., & Lewis, C. (2018). Investigating everyday life in a modernist public housing scheme: The implications of residents’ understandings of well-being and welfare for social work.

Lumsden, K., & Black, A. (2017). Austerity policing, emotional labour and the boundaries of police work: an ethnography of a police force control room in England.

22.5 Phenomenology

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with phenomenological design

- Determine when a phenomenological study design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of phenomenology research?

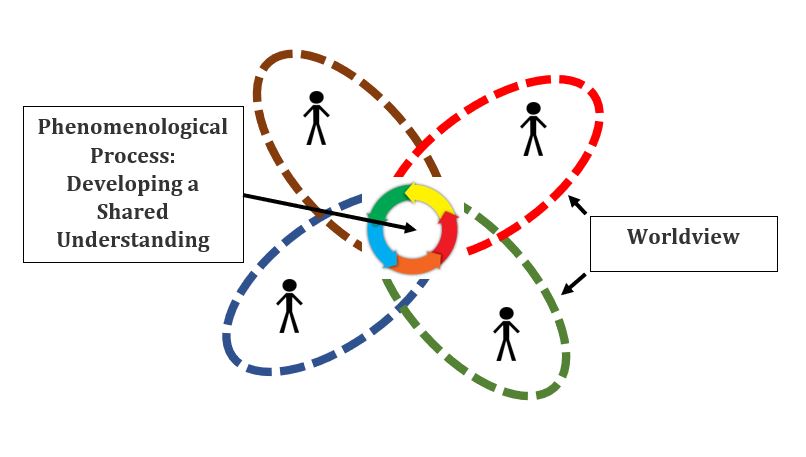

Phenomenology is concerned with capturing and describing the lived experience of some event or “phenomenon” for a group of people. One of the major assumptions in this vein of research is that we all experience and interpret our encounters with the world around us. Furthermore, we interpret these experiences from our own unique worldview, shaped by our beliefs, values and previous encounters. We then go on to attach our own meaning to them. By studying the meaning that people attach to their experiences, phenomenologists hope to understand these experiences in much richer detail. Ideally, this allows them to translate a unidimensional idea that they are studying into a multidimensional understanding that reflects the complex and dynamic ways we experience and interpret our world.

As an example, perhaps we want to study the experience of being a student in a leadership research class, something you might have some first-hand knowledge with. Putting yourself into the role of a participant in this study, each of you has a unique perspective coming into the class. Maybe some of you are excited by school and find classes enjoyable; others may find classes boring. Some may find learning challenging, especially with traditional instructional methods; while others find it easy to digest materials and understand new ideas. You may have heard from your friends, who took this class last year, that research is hard and the professor is evil; while the student sitting next to you has a mother who is a researcher and they are looking forward to developing a better understanding of what she does. The lens through which you interpret your experiences in the class will likely shape the meaning you attach to it, and no two students will have the exact same experience, even though you all share in the phenomenon—the class itself. As a phenomenologist, I would want to try to capture how various students experienced the class. I might explore topics like: what did you think about the class, what feelings were associated with the class as a whole or different aspects of the class, what aspects of the class impacted you and how, etc. I would likely find similarities and differences across your accounts and I would seek to bring these together as themes to help more fully understand the phenomenon of being a student in a leadership research class. From a more professionally practical standpoint, I would challenge you to think about your current or future students. Which of their experiences might it be helpful for you to better understand as you are teaching them? Here are some general examples of phenomenological questions that might apply to your work:

- What does it mean to be part of an organization or a movement?

- What is it like to ask for help or seek assistance in learning?

- What is it like to learn with a learning disability?

- What do people go through when they experience discrimination or bullying based on some characteristic or ascribed status?

Just to recap, phenomenology assumes that…

- Each person has a unique worldview, shaped by their life experiences

- This worldview is the lens through which that person interprets and makes meaning of new phenomena or experiences

- By researching the meaning that people attach to a phenomenon and bringing individual perspectives together, we can potentially arrive at a shared understanding of that phenomenon that has more depth, detail and nuance than any one of us could possess individually.

This figure provides a visual interpretation of these assumptions.

What is involved in phenomenology research?

Again, phenomenological studies are best suited for research questions that center around understanding a number of different peoples’ experiences of particular event or condition, and the understanding that they attach to it. As such, the process of phenomenological research involves gathering, comparing, and synthesizing these subjective experiences into one more comprehensive description of the phenomenon. After reading the results of a phenomenological study, a person should walk away with a broader, more nuanced understanding of what the lived experience of the phenomenon is.

While it isn’t a hard and fast rule, you are most likely to use purposive sampling to recruit your sample for a phenomenological project. The logic behind this sampling method is pretty straightforward since you want to recruit people that have had a specific experience or been exposed to a particular phenomenon, you will intentionally or purposefully be reaching out to people that you know have had this experience. Furthermore, you may want to capture the perspectives of people with different worldviews on your topic to support developing the richest understanding of the phenomenon. Your goal is to target a range of people in your recruitment because of their unique perspectives.

For instance, let’s say that you are interested in studying the subjective experience of having a diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). We might imagine that this experience would be quite different across time periods (e.g. the 1980’s vs. the 2010’s), geographic locations (e.g. New York City vs. the Kingdom of Eswatini in southern Africa), and social group (e.g. Conservative Christian church leaders in the southern US vs. sex workers in Brazil). By using purposive sampling, we are attempting to intentionally generate a varied and diverse group of participants who all have a lived experience of the same phenomenon. Of course, a purposive recruitment approach assumes that we have a working knowledge of who has encountered the phenomenon we are studying. If we don’t have this knowledge, we may need to use other non-probability approaches, like convenience or snowball sampling. Depending on the topic you are studying and the diversity you are attempting to capture, Creswell (2013) suggests that a reasonable sample size may range from 3 -25 participants for a phenomenological study. Regardless of which sample size you choose, you will want a clear rationale that supports why you chose it.

Most often, phenomenological studies rely on interviewing. Again, the logic here is pretty clear—if we are attempting to gather people’s understanding of a certain experience, the most direct way is to ask them. We may start with relatively unstructured questions: “can you tell me about your experience with…..”, “what was it it like to….”, “what does it mean to…”. However, as our interview progresses, we are likely to develop probes and additional questions, leading to a semi-structured feel, as we seek to better understand the emerging dimensions of the topic that we are studying. Phenomenology embodies the iterative process that has been discussed; as we begin to analyze the data and detect new concept or ideas, we will integrate that into our continuing efforts at collecting new data. So let’s say that we have conducted a couple of interviews and begin coding our data. Based on these codes, we decide to add new probes to our interview guide because we want to see if future interviewees also incorporate these ideas into how they understand the phenomenon. Also, let’s say that in our tenth interview a new idea is shared by the participant. As part of this iterative process, we may go back to previous interviewees to get their thoughts about this new idea. It is not uncommon in phenomenological studies to interview participants more than once. Of course, other types of data (e.g. observations, focus groups, artifacts) are not precluded from phenomenological research, but interviewing tends to be the mainstay.

In a general sense, phenomenological data analysis is about bringing together the individual accounts of the phenomenon (most often interview transcripts) and searching for themes across these accounts to capture the essence or description of the phenomenon. This description should be one that reflects a shared understanding as well as the context in which that understanding exists. This essence will be the end result of your analysis.

To arrive at this essence, different phenomenological traditions have emerged to guide data analysis, including approaches advanced by van Manen (2016)[25], Moustakas (1994)[26], Polikinghorne (1989)[27] and Giorgi (2009)[28]. One of the main differences between these models is how the researcher accounts for and utilizes their influence during the research process. Just like participants, it is expected in phenomenological traditions that the researcher also possesses their own worldview. The researcher’s worldview influences all aspects of the research process and phenomenology generally encourages the researcher to account for this influence. This may be done through activities like reflexive journaling (discussed in Chapter 20 on qualitative rigor) or through bracketing (discussed in Chapter 19 on qualitative analysis), both tools helping researchers capture their own thoughts and reactions towards the data and its emerging meaning. Some of these phenomenological approaches suggest that we work to integrate the researcher’s perspective into the analysis process, like van Manen; while others suggest that we need to identify our influence so that we can set it aside as best as possible, like Moustakas (Creswell, 2013).[29] For a more detailed understanding of these approaches, please refer to the resources listed for these authors in the box below.

Key Takeaways

- Phenomenology is a qualitative research tradition that seeks to capture the lived experience of some social phenomenon across some group of participants who have direct, first-hand experience with it.

- As a phenomenological researcher, you will need to bring together individual experiences with the topic being studied, including your own, and weave them together into a shared understanding that captures the “essence” of the phenomenon for all participants.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- As you think about the areas of social work that you are interested in, what life experiences do you need to learn more about to help develop your empathy and humility as a social work practitioner in this field of practice?

Resources

To learn more about phenomenological research

Errasti‐Ibarrondo et al. (2018). Conducting phenomenological research: Rationalizing the methods and rigour of the phenomenology of practice.

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Koopman, O. (2015). Phenomenology as a potential methodology for subjective knowing in science education research. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 15, (1).

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Newberry, A. M. (2012). Social work and hermeneutic phenomenology.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer.

Seymour, T. (2019, January, 30). Phenomenological qualitative research design.

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. New York: Routledge.

For examples of phenomenological research

Haskins, Johnson, L., Finan, R., Edirmanasinghe, N., & Brant‐Rajahn, S. (2022). Latinx and Asian trainees counseling White clients: An interpretative phenomenology. Counselor Education and Supervision, 61(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12229. Available from the SFU Library.

Kang, S. K., & Kim, E. H. (2014). A phenomenological study of the lived experiences of Koreans with mental illness.

(2021) Transformational leaders in higher education administration: understanding their profile through phenomenology, Asia Pacific Journal of Education, DOI: 10.1080/02188791.2021.1987185. Available from the SFU library.

22.6 Narrative

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features associated with narrative design

- Determine when a narrative design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of narrative research?

As you savvy learners have likely surmised, narrative research, often referred to as narrative inquiry, is all about the narrative. For our purposes, narratives will be defined as those stories that we compose that allow us to make meaning of the world. Therefore, narrative inquiry is attempting to develop a rich understanding of what those narratives are, and weave them into a grander narrative that attempts to capture the unique and shared meanings we attach to our individual narratives. In other words, as narrative researchers, we want to understand how we make sense of what happens to us and around us.

As educators, our profession is well-acquainted with the power of narratives[30]. Narrative inquiry prompts research participants to share the stories they have regarding the topic we are studying. Just as we discussed in our chapter on qualitative data gathering, our aim in narrative inquiry is to elicit and understand stories to help the audience that consumes our research (whether that is providers, other researchers, politicians, community members) to better understand or appreciate the worldview of the population we are studying.

Fraser (2004)[31] suggests that narrative approaches are particularly well-suited for helping researchers to:

- make sense of language(s) that are used by individuals and groups

- examine multiple perspectives

- better understand human interactions

- develop an appreciation for context

- reduce our role as an expert (we are most called here to be skillful listeners)

- elevate the stories and perspectives of people who may be otherwise be disenfranchised or silenced

Narrative inquiry may be a good fit for your research proposal if you are looking to study some person/groups’ understanding of an event, situation, role, period of time, or occurrence. Again, think about it like a story; what would you form your story plot around. The answer to that gets at the core of your research question for narrative inquiry. You want to understand some aspect of life more clearly through your participant’s eyes. After all, that is what a good story does, transports us into someone else’s world. As a student, you may not be able to access students directly as research participants, but there are many people around you in your placement, at school, or in the community who may have valuable insights/perspectives on the topic you are interested in studying. In addition, you may be able to access publicly available sources that give you narrative information about a topic: autobiographies, memoirs, oral histories, blogs, journals, editorials, etc. These sources give you indirect information about how the author sees the world —just what you’re looking for! These can become sources of data for you.

What is involved in narrative research?

At the risk of oversimplifying the process of narrative research, it is a journey with stories: finding stories, eliciting stories, hearing and capturing stories, understanding stories, integrating stories, and presenting stories. That being said, each leg of this journey is marked with its own challenges (and rewards!). We won’t be diving deeply into each of these, but we will take time to think through a couple of brief considerations at each of these phases. As you read through these phases, be aware that they reflect the iterative nature of qualitative work that we have discussed previously. This means you won’t necessarily complete one and move on to the next. For instance, you make be in the process of analyzing some of the data you have gathered (phase: understanding stories) and realize that a participant has just blown your mind with a new revelation that you feel like you need to learn more about to adequately complete your research. To do so, you may need to go back to other participants to see if they had similar experiences (phase: eliciting stories) or even go out and do some more recruitment of people who might share in this storyline (phase: finding new stories).

Finding stories

It can feel a bit daunting at first to consider where you would look to find narrative data. We have to determine who possesses the stories we want to hear that will help us to best answer our research question. However, don’t dismay! Stories are all around us. As suggested earlier, as humans, we are constantly evolving stories that help us to make sense of our world, whether we are aware of it or not. Narrative data is not usually just drawn from one source, so this often means thoughtfully seeking out a variety of stories about the topic we are studying. This can include interviews, observations, and a range of other artifacts. As you are thinking about your sample, consult back to Chapter 17 on qualitative sampling to aid you in developing your sampling strategy.

Eliciting stories

So, now you know where you want to get your narrative data, but how will you draw these stories out? As decent and ethical researchers, our objective is to have people share their stories with us, being fully informed about the research process and why we are asking them to share their stories. But this just gets our proverbial foot in the door. Next, we have to get people to talk, to open up and share. Just like in practice settings, this involves the thoughtful use of well-planned open-ended questions. Narrative studies often involve relatively unstructured interviews, where we provide a few broad questions in the hopes of getting people to expound on their perspective. However, we anticipate that we might need to have some strategic probes to help prompt the storytelling process. We also might be looking to extract narrative data from artifacts, in which case the data is there, we just need to locate and make sense of it.

Hearing and capturing stories

We need to listen! While we value [hopefully] the art of listening as educators, we need to make sure that we are clear what we are listening for. In narrative research we are listening for important narrative detail. Fraser (2004)[32] identifies that it is important to listen for emotions that the story conveys, the evolution or unfolding of the story, and last but not least, our own reactions. Additionally, we need to consider how we will capture the story—will we record it or will we take field notes? Again, we may be drawing narrative data from artifacts. If this is the case, we are “listening” with our eyes and through our careful review of materials and detailed note-taking.

Understanding stories

As we are listening, we are attending to many things as we go through this part of the analysis: word choice and meaning, emotions that are expressed/provoked, context of what is being shared, themes or main points, and changes in tone. We want to pay attention to both what the story is and how is it being told.

Integrating stories

Part of the work (and perhaps the most challenging part) of narrative research is the bringing together of many stories. We aim to look across the stories that are shared with us through the data we have gathered and ultimately converge on a narrative that honors both the diversity and the commonality that is reflected therein, all the while tracking our own personal story and the influence it has on shaping the evolving narrative. No small task! While integrating stories, Fraser (2004)[33] also challenges us to consider how these stories coming together are situated within broader socio-political-structural contexts that need to be acknowledged.

Key Takeaways

- The aim of narrative research is to uncover the stories that humans tell themselves to make sense of the world.

- To turn these stories into research, we need to systematically listen, understand, compare, and eventually combine these into one meta-narrative, providing us with a deeper appreciation of how participants comprehend the issue we are studying.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

Know that we have reviewed a number of qualitative designs, reflect on the following questions:

- Which designs suit you well as a social work researcher? What is it about these designs that resonate with you?

- Which designs would really challenge you as a social work researcher? What is it about these designs that make you apprehensive or uneasy?

- What design is best suited for your research question? Is your answer here being swayed by personal preferences?

Resources

To learn more about narrative inquiry

Fraser, H. (2004). Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work, 3(2), 179-201. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1473325004043383

Larsson, S., & Sjöblom, Y. (2010). Perspectives on narrative methods in social work research. International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(3), 272-280.https://insights.ovid.com/international-social-welfare/ijsow/2010/07/000/perspectives-narrative-methods-social-work/3/00125820

Rudman, D.L. (2018, August, 24). Narrative inquiry: What’s your story? [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rPyomRrBn_g

Shaw, J. (2017). A renewed call for narrative inquiry as a social work epistemology and methodology. Canadian Social Work Review, 34(2). https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cswr/2017-v34-n2-cswr03365/1042889ar/

Writing@CSU, the Writing Studio: Colorado State University. (n.d.). Narrative inquiry. [Webpage]. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/page.cfm?pageid=1346&guideid=63

For examples of narrative studies

Balogh, A. (2016). A narrative inquiry of charter school social work and the “No Excuses” Behavior Model. Columbia Social Work Review, 14(1), 19-25. https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/cswr/article/view/1855

Klausen, R. K., Blix, B. H., Karlsson, M., Haugsgjerd, S., & Lorem, G. F. (2017). Shared decision making from the service users’ perspective: A narrative study from community mental health centers in northern Norway. Social Work in Mental Health, 15(3), 354-371. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15332985.2016.1222981

Lietz, C. A., & Strength, M. (2011). Stories of successful reunification: A narrative study of family resilience in child welfare. Families in Society, 92(2), 203-210. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1606/1044-3894.4102

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2013). The constructivist credo. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. ↵

- Robertson, I. [Ian Robertson]. (2007, May 13). Naturalistic or constructivist inquiry [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAXEBHuSNWk&feature=youtu.be ↵

- Rodwell, M.K. (1998). Social work constructivist research. New York: Routledge ↵

- Rodwell, M.K. (1998). Social work constructivist research. New York: Routledge ↵

- Oberg, M. G., & Andenoro, A. C. (2019). Overcoming leadership learning barriers: A naturalistic examination for advancing undergraduate leader development. Journal of Leadership Education, 18(3), 53–67. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.12806/V18/I3/R4 ↵

- Philander, C. J., & Botha, M.-L. (2021). Natural sciences teachers’ continuous professional development through a Community of Practice. South African Journal of Education, 41(4), 1–11. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/10.15700/saje.v41n4a1918 ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Columbia Center for Oral History Research at Incite (n.d.). Human Rights Campaign Oral History Project. [Webpage]. https://www.ccohr.incite.columbia.edu/human-rights-campaign-oral-history ↵

- Groundswell. (n.d.). Groundswell: Oral history for social change. [Webpage]. http://www.oralhistoryforsocialchange.org/ ↵

- Moyer, J. (1999). Step-by-step guide to oral history. [Webpage]. http://dohistory.org/on_your_own/toolkit/oralHistory.html#WHATIS ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Silva, Y. (2019, November 8). Oral history training: 8 basic principles of oral history. Citaliarestauro. [Blogpost]. https://citaliarestauro.com/en/oral-history-training/ ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Silva, Y. (2019, November 8). Oral history training: 8 basic principles of oral history. Citaliarestauro. [Blogpost]. https://citaliarestauro.com/en/oral-history-training/ ↵

- The American Foklife Center. (n.d.). Oral history interviews. The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/folklife/familyfolklife/oralhistory.html#planning ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Silva, Y. (2019, November 8). Oral history training: 8 basic principles of oral history. Citaliarestauro. [Blogpost]. https://citaliarestauro.com/en/oral-history-training/ ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- The American Foklife Center. (n.d.). Oral history interviews. The Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/folklife/familyfolklife/oralhistory.html#planning ↵

- Oral History Association, OHA (2009). Principles and best practices. [Webpage]. https://www.oralhistory.org/about/principles-and-practices-revised-2009/ ↵

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles Sage. ↵

- Hammersley, M. (1990). What's wrong with ethnography? The myth of theoretical description. Sociology, 24(4), 597-615. ↵

- van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. New York: Routledge. ↵

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer. ↵

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. ↵

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles Sage. ↵

- Collins. (1999). The Use of Traditional Storytelling in Education to the Learning of Literacy Skills. Early Child Development and Care, 152(1), 77–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443991520106 ↵

- Fraser, H. (2004). Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work, 3(2), 179-201. ↵

- Fraser, H. (2004). Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work, 3(2), 179-201. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1473325004043383 ↵

- Fraser, H. (2004). Doing narrative research: Analysing personal stories line by line. Qualitative Social Work, 3(2), 179-201. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1473325004043383 ↵

Case studies are a type of qualitative research design that focus on a defined case and gathers data to provide a very rich, full understanding of that case. It usually involves gathering data from multiple different sources to get a well-rounded case description.

Findings form a research study that apply to larger group of people (beyond the sample). Producing generalizable findings requires starting with a representative sample.

a paradigm guided by the principles of objectivity, knowability, and deductive logic

a paradigm based on the idea that social context and interaction frame our realities

A thick description is a very complete, detailed, and illustrative of the subject that is being described.

Rigor is the process through which we demonstrate, to the best of our ability, that our research is empirically sound and reflects a scientific approach to knowledge building.

The details/steps outlining how a study will be carried out.

Context is the circumstances surrounding an artifact, event, or experience.

Constructivist research is a qualitative design that seeks to develop a deep understanding of the meaning that people attach to events, experiences, or phenomena.

Research findings are applicable to the group of people who contributed to the knowledge building and the situation in which it took place.

As researchers in the social science, we ourselves are the main tool for conducting our studies.

ensuring that we have correctly captured and reflected an accurate understanding in our findings by clarifying and verifying our findings with our participants

Oral histories are a type of qualitative research design that offers a detailed accounting of a person's life, some event, or experience. This story(ies) is aimed at answering a specific research question.

Ethnography is a qualitative research design that is used when we are attempting to learn about a culture by observing people in their natural environment.

Concept advanced by Albert Bandura that human behavior both shapes and is shaped by their environment.

A qualitative research design that aims to capture and describe the lived experience of some event or "phenomenon" for a group of people.

In a purposive sample, participants are intentionally or hand-selected because of their specific expertise or experience.

A convenience sample is formed by collecting data from those people or other relevant elements to which we have the most convenient access. Essentially, we take who we can get.

For a snowball sample, a few initial participants are recruited and then we rely on those initial (and successive) participants to help identify additional people to recruit. We thus rely on participants connects and knowledge of the population to aid our recruitment.

An iterative approach means that after planning and once we begin collecting data, we begin analyzing as data as it is coming in. This early analysis of our (incomplete) data, then impacts our planning, ongoing data gathering and future analysis as it progresses.

Often the end result of a phenomological study, this is a description of the lived experience of the phenomenon being studied.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study

A qualitative research technique where the researcher attempts to capture and track their subjective assumptions during the research process. * note, there are other definitions of bracketing, but this is the most widely used.

Those stories that we compose as human beings that allow us to make meaning of our experiences and the world around us

Probes a brief prompts or follow up questions that are used in qualitative interviewing to help draw out additional information on a particular question or idea.

Notes that are taken by the researcher while we are in the field, gathering data.