17

Chapter Outline

- Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness (7 minute read)

- Critical considerations (8 minute read)

- Find the right qualitative data to answer my research question (17 minute read)

- How to gather a qualitative sample (21 minute read)

- What should my sample look like? (9 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to substance use, ageism, injustices against the Black community in research (e.g. Henrietta Lacks and Tuskegee Syphillis Study), children and their educational experiences, mental health, research bias, job loss and business closure, mobility limitations, politics, media portrayals of LatinX families, labor protests, neighborhood crime, Batten Disease (childhood disorder), transgender youth, cancer, child welfare including kinship care and foster care, Planned Parenthood, trauma and resilience, sexual health behaviors.

Now let’s change things up! In the previous chapters, we were exploring steps to create and carry out a quantitative research study. Quantitative studies are great when we want to summarize data and examine or test relationships between ideas using numbers and the power of statistics. However, qualitative research offers us a different and equally important tool. Sometimes the aim of research is to explore meaning and experience. If these are the goals of our research proposal, we are going to turn to qualitative research. Qualitative research relies on the power of human expression through words, pictures, movies, performance and other artifacts that represent these things. All of these tell stories about the human experience and we want to learn from them and have them be represented in our research. Generally speaking, qualitative research is about the gathering up of these stories, breaking them into pieces so we can examine the ideas that make them up, and putting them back together in a way that allows us to tell a common or shared story that responds to our research question. Back in Chapter 7 we talked about different paradigms.

Before plunging further into our exploration of qualitative research, I would like to suggest that we begin by thinking about some ethical, cultural and empowerment-related considerations as you plan your proposal. This is by no means a comprehensive discussion of these topics as they relate to qualitative research, but my intention is to have you think about a few issues that are relevant at each step of the qualitative process. I will begin each of our qualitative chapters with some discussion about these topics as they relate to each of these steps in the research process. These sections are specially situated at the beginning of the chapters so that you can consider how these principles apply throughout the proceeding discussion. At the end of this chapter there will be an opportunity to reflect on these areas as they apply specifically to your proposal. Now, we have already discussed research ethics back in Chapter 6. However, as qualitative researchers we have some unique ethical commitments to participants and to the communities that they represent. Our work as qualitative researchers often requires us to represent the experiences of others, which also means that we need to be especially attentive to how culture is reflected in our research. Cultural respectfulness suggests that we approach our work and our participants with a sense of humility. This means that we maintain an open mind, a desire to learn about the cultural context of participants’ lives, and that we preserve the integrity of this context as we share our findings.

17.1 Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain how our ethical responsibilities as researchers translate into decisions regarding qualitative sampling

- Summarize how aspects of culture and identity may influence recruitment for qualitative studies

Representation

Representation reflects two important aspects of our work as qualitative researchers, who is present and how are they presented. First, we need to consider who we are including or excluding in or sample. Recruitment and sampling is especially tied to our ethical mandate as researchers to uphold the principle of justice under the Belmont Report[1] and in Canada, the Tri-Council Policy Statement on the Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (see Chapter 6 for additional information). Within this context we need to:

- Assure there is fair distribution of risks and benefits related to our research

- Be conscientious in our recruitment efforts to support equitable representation

- Ensure that special protections to vulnerable groups involved in research activities are in place

As you plan your qualitative research study, make sure to consider who is invited and able to participate and who is not. These choices have important implications for your findings and how well your results reflect the population you are seeking to represent. There may be explicit exclusions that don’t allow certain people to participate, but there may also be unintended reasons people are excluded (e.g. transportation, language barriers, access to technology, lack of time).

The second part of representation has to do with how we disseminate our findings and how this reflects on the population we are studying. We will speak further about this aspect of representation in Chapter 21, which is specific to qualitative research dissemination. For now, it is enough to know that we need to be thoughtful about who we attempt to recruit and how effectively our resultant sample reflects our population.

Being mindful of history

As you plan for the recruitment of your sample, be mindful of the history of how this group (and/or the individuals you may be interacting with) has been treated – not just by the research community, but by others in positions of power. As researchers, we usually represent an outside influence and the people we are seeking to recruit may have significant reservations about trusting us and being willing to participate in our study (often grounded in good historical reasons—see Chapter 6 for additional information). Because of this, be very intentional in your efforts to be transparent about the purpose of your research and what it involves, why it is important to you, as well as how it can impact the community. Also, in helping to address this history, we need to make concerted efforts to get to know the communities that we research with well, including what is important to them.

Stories as sacred: How are we requesting them?

Finally, it is worth pointing out that as qualitative researchers, we have an extra layer of ethical and cultural responsibility. While quantitative research deals with numbers, as qualitative researchers, we are generally asking people to share their stories. Stories are intimate, full of depth and meaning, and can reveal tremendous amounts about who we are and what makes us tick. Because of this, we need to take special care to treat these stories as sacred. I will come back to this point in subsequent chapters, but as we go about asking for people to share their stories, we need to do so humbly.

Key Takeaways

- As researchers, we need to consider how our participant communities have been treated historically, how we are representing them in the present through our research, and the implications this representation could have (intended and unintended) for their lives. We need to treat research participants and their stories with respect and humility.

- When conducting qualitative research, we are asking people to share their stories with us. These “data” are personal, intimate, and often reflect the very essence of who our participants are. As researchers, we need to treat research participants and their stories with respect and humility.

17.2 Critical considerations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Assess dynamics of power in sampling design and recruitment for individual participants and participant communities

- Create opportunities for empowerment through early choice points in key research design elements

Power

Related to the previous discussion regarding being mindful of history, we also need to consider the current dynamics of power between researcher and potential participant. While we may not always recognize or feel like we are in a position of power, as researchers we hold specialized knowledge, a particular skill set, and what we do with the data we collect can have important implications and consequences for individuals, groups, and communities. All of these contribute to the formation of a role ascribed with power. It is important for us to consider how this power is perceived and whenever possible, how we can build opportunities for empowerment that can be built into our research design. Examples of some strategies include:

- Recruiting and meeting in spaces that are culturally acceptable

- Finding ways to build participant choice into the research process

- Working with a community advisory group during the research process (explained further in the example box below)

- Designing informative and educational materials that help to thoroughly explain the research process in meaningful ways

- Regularly checking with participants for understanding

- Asking participants what they would like to get out of their participation and what it has been like to participate in our research

- Determining if there are ways that we can contribute back to communities beyond our research (developing an ongoing commitment to collaboration and reciprocity)

While it may be beyond the scope of a student research project to address all of these considerations, I do think it is important that we start thinking about these more in our research practices. As social science researchers, we should be modeling empowerment practices in the field of education research, but we often fail to meet this standard.

Example. A community advisory group can be a tremendous asset throughout our research process, but especially in early stages of planning, including recruitment. I was fortunate enough to have a community advisory group for one of the projects I worked on. They were incredibly helpful as I considered different perspectives I needed to include in my study, helping me to think through a respectful way to approach recruitment, and how we might make the research arrangement a bit more reciprocal so community members might benefit as well.

Intersectional identity

As qualitative researchers, we are often not looking to prove a hypothesis or uncover facts. Instead, we are generally seeking to expand our understanding of the breadth and depth of human experience. Breadth is reflected as we seek to uncover variation across participants and depth captures variation or detail within each participants’ story. Both are important for generating the fullest picture possible for our findings. For example, we might be interested in learning about students’ experiences living in a dorms by interviewing residents. We would want to capture a range of different residents’ experiences (breadth) and for each student, we would seek as much detail as possible (depth). Do note, sometimes our research may only involve one person, setting, or issue, such as in a case study. However, in these instances we are usually trying to understand many aspects or dimensions of that single case.

To capture this breadth and depth we need to remember that people are made of multiple stories formed by intersectional identities. This means that our participants never just represent one homogeneous social group. We need to consider the various aspects of our population that will help to give the most complete representation in our sample as we go about recruitment.

Exercises

Identify a population you are interested in studying. This might be a population you are working with at your school (either directly or indirectly), a group you are especially interested in learning more about, or a community you want to serve in the future. As you formulate your question, you may draw your sample directly from participants that are being served, others in their support network, service providers that are providing services, or other stakeholders that might be invested in the well-being of this group or community. Below, list out two populations you are interested in studying and then for each one, think about two groups connected with this population that you might focus your study on.

| Population | Group |

| 1. | 1a. |

| 1b. | |

| 2. | 2a. |

| 2b. |

Next, think about what kind of information might help you understand this group better. If you had the chance to sit down and talk with them, what kinds of things would you want to ask? What kinds of things would help you understand their perspective or their worldview more clearly? What kinds of things do we need to learn from them and their experiences that could help us to be better educators? For each of the groups you identified above, write out something you would like to learn from their experience.

| Population | Group | What I would like to learn from their experience |

| 1 | 1a. | 1a. |

| 1b. | 1b. | |

| 2. | 2a. | 2a. |

| 2b. | 2b. |

Finally, consider how this group might perceive a request to participate. For the populations and the groups that you have identified, think about the following questions:

- How have these groups been represented in the news?

- How have these groups been represented in popular culture and popular media?

- What historical or contemporary factors might influence these group members’ opinions of research and researchers?

- In what ways have these groups been oppressed and how might research or academic institutions have contributed to this oppression?

Our impact on the qualitative process

It is important for qualitative researchers to thoughtfully plan for and attempt to capture our own impact on the research process. This influence that we can have on the research process represents what is known as researcher bias. This requires that we consider how we, as human beings, influence the research we conduct. This starts at the very beginning of the research process, including how we go about sampling. Our choices throughout the research process are driven by our unique values, experiences, and existing knowledge of how the world works. To help capture this contribution, qualitative researchers may plan to use tools like a reflexive journal, which is a research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how these may influence or shape a study (there will be more about this tool in Chapter 20 when we discuss the concept of rigor). While this tool is not specific to the sampling process, the next few chapters will suggest reflexive journal questions to help you think through how it might be used as you develop a qualitative proposal.

Example. To help demonstrate the potential for researcher bias, consider a number of students that I work with who are placed in school systems for their field experience and choose to focus their research proposal in this area. Some are interested in understanding why parents or guardians aren’t more involved in their children’s educational experience. While this might be an interesting topic, I would encourage students to consider what kind of biases they might have around this issue.

- What expectations do they have about parenting?

- What values do they attach to education and how it should be supported in the home?

- How has their own upbringing shaped their expectations?

- What do they know about the families that the school district serves and how did they come by this information?

- How are these families’ life experiences different from their own?

The answers to these questions may unconsciously shape the early design of the study, including the research question they ask and the sources of data they seek out. For instance, their study may only focus on the behaviors and the inclinations of the families, but do little to investigate the role that the school plays in engagement and other structural barriers that might exist (e.g. language, stigma, accessibility, child-care, financial constraints, etc.).

Key Takeaways

- As researchers, we wield (sometimes subtle) power and we need to be conscientious of how we use and distribute this power.

- Qualitative study findings represent complex human experiences. As good as we may be, we are only going to capture a relatively small window into these experiences (and need to be mindful of this when discussing our findings).

Exercises

In the early stages of your research process, it is a good idea to start your reflexive journal. Starting a reflexive journal is as easy as opening up a new word document, titling it and chronologically dating your entries. If you are more tactile-oriented, you can also keep your reflexive journal in paper bound journal.

To prompt your initial entry, put your thoughts down in response to the following questions:

- What led you to be interested in this topic?

- What experience(s) do you have in this area?

- What knowledge do you have about this issue and how did you come by this knowledge?

- In what ways might you be biased about this topic?

Don’t answer this last question too hastily! Our initial reaction is often—”Biased!?! Me—I don’t have a biased bone in my body! I have an open-mind about everything, toward everyone!” After all, much of our education directs us towards acceptance and working to understand the perspectives of others. However, WE ALL HAVE BIASES. These are conscious or subconscious preferences that lead us to favor some things over others. These preferences influence the choices we make throughout the research process. The reflexive journal helps us to reflect on these preferences, where they might stem from, and how they might be influencing our research process. For instance, I spent K-12 in public schools and earned both my undergraduate and Maters degree from publicly funded universities. I also taught for seven years in public schools. As a result, I carry with me a strong belief in the value and importance of a strong public education system. For me that influences my approach to both teaching and research. For instance, I may be biased toward teachers and understanding the challenging nature of their work. My belief in the value of public education may cause me to critical of efforts to privatize education systems. However, other education researchers may well have very different perceptions based on their experiences or beliefs.

17.3 Finding the right qualitative data to answer my research question

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Compare different types of qualitative data

- Begin to formulate decisions as they build their qualitative research proposal, specially in regards to selecting types of data that can effectively answer their research question

Sampling starts with deciding on the type of data you will be using. Qualitative research may use data from a variety of sources. Sources of qualitative data may come frominterviews or focus groups, observations, a review of written documents, administrative data, or other forms of media, and performances. While some qualitative studies rely solely on one source of data, others incorporate a variety.

You should now be well acquainted with the term triangulation. When thinking about triangulation in qualitative research, we are often referring to our use of multiple sources of data among those listed above to help strengthen the confidence we have in our findings. Drawing on a journalism metaphor, this allows us to “fact check” our data to help ensure that we are getting the story correct. This can mean that we use one type of data (like interviews), but we intentionally plan to get a diverse range of perspectives from people we know will see things differently. In this case we are using triangulation of perspectives. In addition, we may also you a variety of different types of data, like including interviews, data from policy documents, and staff meeting minutes all as data sources in the same study. This reflects triangulation through types of data.

As a student conducting research, you may not always have access to vulnerable groups or communities in need, or it may be unreasonable for you to collect data from them directly due to time, resource, or knowledge constraints. Because of this, as you are reviewing the sections below, think about accessible alternative sources of data that will still allow you to answer your research question practically, and I will provide some examples along the way to get you started. In the above example, local media coverage might be a means of obtaining data that does not involve directly collecting data from potentially vulnerable participants.

Verbal data

Perhaps the bread and butter of the qualitative researcher, we often rely on what people tell us as a primary source of information for qualitative studies in the form of verbal data. The researcher who schedules interviews with recipients of public scholarships to capture their experience after legislation drastically changes the funding associated with the scholarship relies on the communication between the researcher and the impacted recipients. Focus groups are another frequently used method of gathering verbal data. Focus groups bring together a group of participants to discuss their unique perspectives and explore commonalities on a given topic. One such example is a researcher who brings together a group of early career teachers who have been teaching for one to two years to ask them questions regarding their preparation, experiences, and perceptions regarding their work.

A benefit of utilizing verbal data is that it offers an opportunity for researchers to hear directly from participants about their experiences, opinions, or understanding of a given topic. Of course, this requires that participants be willing to share this information with a researcher and that the information shared is genuine. If groups of participants are unwilling to participate in sharing verbal data or if participants share information that somehow misrepresents their true feelings (perhaps because they feel intimidated by the research process or concerned about what the researcher will think of them), then our qualitative sample can become biased and lead to inaccurate or partially accurate findings.

As noted above, participant willingness and honesty can present challenges for qualitative researchers. You may face similar challenges as a student gathering verbal data directly from participants who have been personally affected by your research topic. Because of this, you might want to gather verbal data from other sources. Many of the students I work with are placed in schools. It is not feasible for them to interview the youth they work with directly, so frequently they will interview other professionals in the school, such as teachers, counsellors, administration, and other staff. You might also consider interviewing other students about their perceptions or experiences working with a particular group.

Again, because it may be problematic or unrealistic for you to obtain verbal data directly from vulnerable groups as a student researcher, you might consider gathering verbal data from the following sources:

- Interviews and focus groups with other teachers, education students, faculty, the general public, administrators, local politicians, advocacy groups

- Public blogs of people invested in your topic

- Publicly available transcripts from interviews with experts in the area or people reporting experiences in popular media

Make sure to consider, and consult with your supervisor about, whether what you are planning will be realistic for the purposes of your study.

Observational data

As researchers, we sometimes rely on our own powers of observation to gather data on a particular topic. We may observe a person’s behavior, an interaction, setting, context, and maybe even our own reactions to what we are observing (i.e. what we are thinking or feeling). When observational data is used for quantitative purposes, it involves a count, such as how many times a certain behavior occurs for a child in a classroom. However, when observational data is used for qualitative purposes, it involves the researcher providing a detailed description. For instance, a qualitative researcher may conduct observations of how teachers and students interact in homeroom, and take notes about where exchanges take place, topics of conversation, nonverbal information, and data about the setting itself – what the room looks like, how it is arranged, the lighting, photos on the wall, etc.

Observational data can provide important contextual information that may not be captured when we rely solely on verbal data. However, using this form of data requires us, as researchers, to correctly observe and interpret what is going on. As we don’t have direct access to what participants may be thinking or feeling to aid us (which can lead us to misinterpret or create a biased representation of what we are observing), our take on this situation may vary drastically from that of another person observing the same thing. For instance, if we observe two people talking and one begins crying, how do we know if these are tears of joy or sorrow? When you observe someone being abrupt in a conversation, I might interpret that as the person being rude while you might perceive that the person is distracted or preoccupied with something. The point is, we can’t know for sure. Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects of gathering observational data is collecting neutral, objective observations, that are not laden with our subjective value judgments placed on them. Students often find this out in class during one of our activities. For this activity, they have to go out to public space and write down observations about what they observe. When they bring them back to class and we start discussing them together, we quickly realize how often we make (unfounded) judgments. Frequent examples from our class include determining the race/ethnicity of people they observe or the relationships between people, without any confirmational knowledge. Additionally, they often describe scenarios with adverbs and adjectives that reflect judgments and values they are placing on their data. I’m not sharing this to call them out, in fact, they do a great job with the assignment. I just want to demonstrate that as human beings, we are often less objective than we think we are! These are great examples of researcher bias.

Again, gaining access to observational spaces, especially private ones, might be a challenge for you as a student. As such, you might consider if observing public spaces might be an option. If you do opt for this, make sure you are not violating anyone’s right to privacy. For instance, gathering information in a narcotics anonymous meeting or a religious celebration might be perceived as offensive, invasive or in direct opposition to values (like anonymity) of participants. When making observations in public spaces be careful not to gather any information that might identify specific individuals or organizations. Also, it is important to consider the influence your presence may have on a community or classroom, particularly if your observation makes you stand out among those typically present in that setting. Always consider the needs of the individual and the communities in formulating a plan for observing public behavior. Public spaces might include commercial spaces or events open to the public as well as municipal parks. Below we will have an expanded discussion about different varieties of non-probability sampling strategies that apply to qualitative research. Recruiting in public spaces like these may work for strategies such as convenience sampling or quota sampling, but would not be a good choice for snowball sampling or purposive sampling.

As with the cautionary note for student researchers under verbal data, you may experience restricted access to spaces in which you are able to gather observational data. However, if you do determine that observational data might be a good fit for your proposal, you might consider the following spaces:

- Shopping malls

- Public parks or sporting arenas

- Public meetings or rallies

- Public transportation

Private spaces might include:

- Classrooms

- School facilities (hallways, dining areas, the library)

- School grounds (parking lot, playground, athletic fields

Artifacts (documents & other media)

Existing artifacts can also be very useful for the qualitative researcher. Examples include newspapers, blogs, websites, podcasts, television shows, movies, pictures, video recordings, artwork, and live performances. While many of these sources may provide indirect information on a topic, this information can still be quite valuable in capturing the sentiment of popular culture and thereby help researchers enhance their understanding of (dominant) societal values and opinions. Conversely, researchers can intentionally choose to seek out divergent, unique or controversial perspectives by searching for artifacts that tend to take up positions that differ from the mainstream, such as independent publications and (electronic) newsletters. While we will explore this further below, it is important to understand that data and research, in all its forms, is political. Among many other purposes, it is used to create, critique, and change policy; to engage in activism; to support and refute how organizations function; to sway public opinion; or to make a profit.

When utilizing documents and other media as artifacts, researchers may choose to use an entire source (such as a book or movie), or they may use a segment or portion of that artifact (such as the front-page stories from newspapers, or specific scenes in a television series). Your choice of which artifacts you choose to include will be driven by your question, and remember, you want your sample of artifacts to reflect the diversity of perspectives that may exist in the population you are interested in. For instance, perhaps I am interested in studying how various forms of media portray teachers. I might intentionally include a range of liberal to conservative views that are portrayed across a number of media sources.

As qualitative researchers using artifacts, we often need to do some digging to understand the context of said artifact. We do this because data is almost always affiliated or aligned with some position (again, data is political). To help us consider this, it may be helpful to reflect on the following questions:

- Who owns the artifact or where is it housed

- What values does the owner (organization or person) hold

- How might the position or identity of the owner influence what information is shared or how it is portrayed

- What is the purpose of the artifact

- Who is the audience for which the artifact is intended

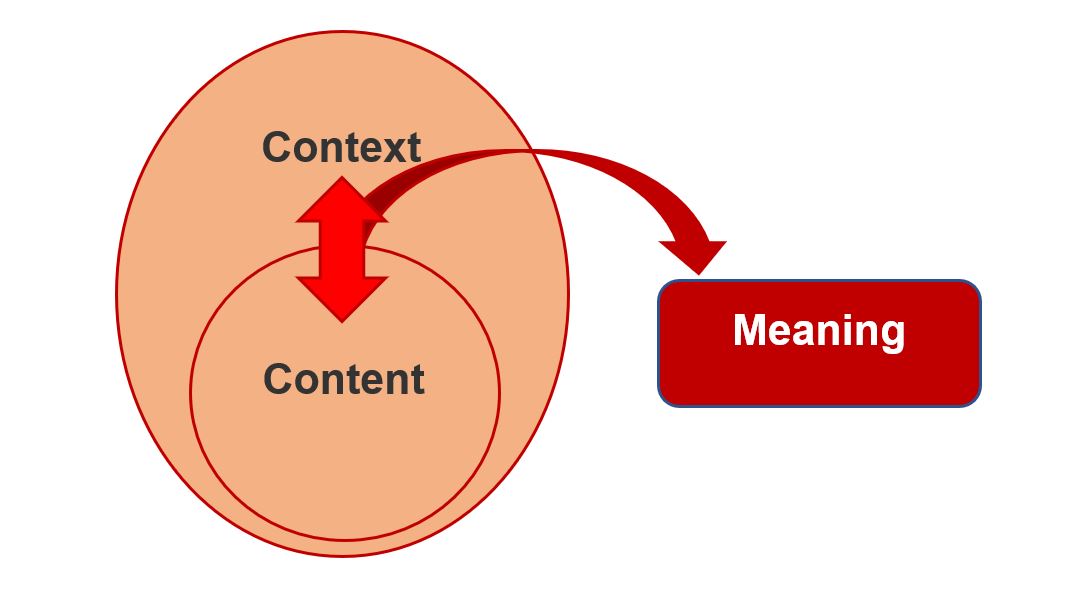

Answers to questions such as these can help us to better understand and give meaning to the content of the artifacts. Content is the substance of the artifact (e.g. the words, picture, scene). While context is the circumstances surrounding content. Both work together to help provide meaning, and further understanding of what can be derived from an artifact. As an example to illustrate this point, let’s say that you are including meeting minutes from school board meetings as a source of data for your study. The narrative description in these minutes will certainly be important, however, they may not tell the whole story. For instance, you might not know from the text that the school board has recently voted in a new, but controversial, chair and this has created significant division within the board. Knowing this information might help you to interpret the agenda and the discussion contained in the minutes very differently.

As student researchers, using documents and other artifacts may be a particularly appealing source of data for your study. This is because this data already exists (you aren’t creating new data) and depending on what you select, it might be relatively easy to access. Examples of utilizing existing artifacts might include studying the cultural context of movie portrayals of teachers or analyzing publicly available town hall meeting minutes to explore expressions of social capital. Below is a list of sources of data from documents or other media sources to consider for your student proposal:

- Movies or TV shows

- Music or music videos

- Public blogs

- Policies or other organizational documents

- Meeting minutes

- Comments in online forums

- Books, newspapers, magazines, or other print/virtual text-based materials

- Recruitment, training, or educational materials

- Musical or artistic expressions

- Policy documents (legislation, regulations, or rules)

Photovoice

Finally, Photovoice is a technique that merges pictures with narrative (word or voice) data that helps interpret the meaning or significance of the visual. Photovoice is often used for qualitative work that is conducted as part of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR), wherein community members act as both participants and as co-researchers. These community members are provided with a means of capturing images that reflect their understanding of some topic, prompt or question, and then they are asked to provide a narrative description or interpretation to help give meaning to the image(s). Both the visual and narrative information are used as qualitative data to include in the study. Dissemination of Photovoice projects often involve a public display of the works, such as through a demonstration or art exhibition to raise awareness or to produce some specific change that is desired by participants. Because this form of study is often intentionally persuasive in nature, we need to recognize that this form of data will be inherently subjective. As a student, it may be particularly challenging to implement a Photovoice project, especially due to its time-intensive nature, as well as the additional commitments of needing to engage, train, and collaborate with community partners.

| Type of Data | Potential Sources of Student Data | Some Potential Strengths and Challenges with this Type of Data |

| Verbal |

|

Strengths

Challenges

|

| Type of Data | Potential Sources of Student Data | Some Potential Strengths and Challenges with this Type of Data |

| Observational | Observations in:

|

Strengths

Challenges

|

| Type of Data | Potential Sources of Student Data | Some Potential Strengths and Challenges with this Type of Data |

| Documents & Other Media |

|

Strengths

Challenges

|

How many kinds of data?

You will need to consider whether you will rely on one kind of data or multiple. While many qualitative studies solely use one type of data, such as interviews or focus groups, others may use multiple sources. The decision to use multiple sources is often made to help strengthen the confidence we have in our findings or to help us to produce a richer, more detailed description of our results. For instance, if we are conducting a case study of what the learning experience is for a child with a severe learning disorder, we may use multiple sources of data. These can include observing learning interactions, conducting interviews with family members and others connected to the family (such as teachers, support workers, or psychologists) and examining journal entries families, the student, teachers, or other stakeholders were asked to keep over the course of the study. By collecting data from a variety of sources such as this, we can more broadly represent a range of perspectives when answering our research question, which will hopefully provide a more holistic picture of the student’s experience. However, if we are trying to examine the decision-making processes of building-level administrators, it may make the most sense to rely on just one type of data, such as interviews with assistant principals and principals.

Key Takeaways

- There are numerous types of qualitative data (verbal, observational, artifacts) that we may be able to access when planning a qualitative study. As we plan, we need to consider the strengths and challenges that each possess and how well each type might answer our research question.

- The use of multiple types of qualitative data does add complexity to a study, but this complication may well be worth it to help us explore multiple dimensions of our topic and thereby enrich our findings.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

For your next entry, consider responding to the following:

17.4 How to gather a qualitative sample

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Compare and contrast various non-probability sampling approaches

- Select a sampling strategy that ideologically fits the research question and is practical/actionable

Before we launch into how to plan our sample, I’m going to take a brief moment to remind us of the philosophical basis surrounding the purpose of qualitative research—not to punish you, but because it has important implications for sampling.

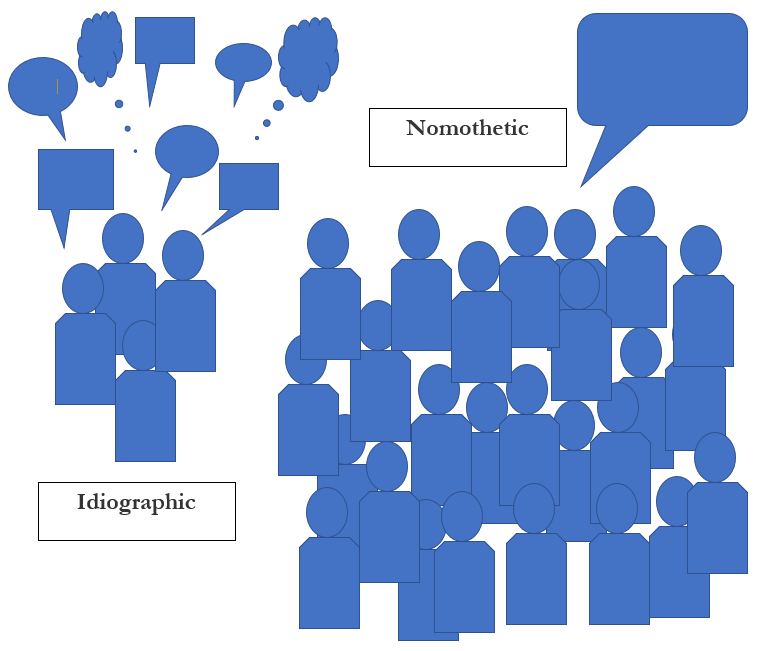

Nomothetic vs. idiographic

As a quick reminder, as we discussed in Chapter 8 idiographic research aims to develop a rich or deep understanding of the individual or the few. The focus is on capturing the uniqueness of a smaller sample in a comprehensive manner. For example, an idiographic study might be a good approach for a case study examining the educational experiences of a transgender youth and her family living in a rural Midwestern state. Data for this idiographic study would be collected from a range of sources, including interviews with family members and teachers, observations of interactions at home, school, and in the community, a focus group with the youth and her friend group, another focus group with the mother and her social network, etc. The aim would be to gain a very holistic picture of this family’s experiences.

On the other hand, nomothetic research is invested in trying to uncover what is ‘true’ for many. It seeks to develop a general understanding of a very specific relationship between variables. The aim is to produce generalizable findings, or findings that apply to a large group of people. This is done by gathering a large sample and looking at a limited or restricted number of aspects. A nomothetic study might involve a national survey of school counsellors in which thousands of counsellors are surveyed regarding their current knowledge and competence in working with transgender individuals. It would gather data from a very large number of people, and attempt to highlight some general findings across this population on a very focused topic.

Idiographic and nomothetic research represent two different research categories existing at opposite extremes on a continuum. Qualitative research generally exists on the idiographic end of this continuum. We are most often seeking to obtain a rich, deep, detailed understanding from a relatively small group of people.

Non-probability sampling

Non-probability sampling refers to sampling techniques for which a person’s (or event’s) likelihood of being selected for membership in the sample is unknown. Because we don’t know the likelihood of selection, we don’t know whether a sample represents a larger population or not. But that’s okay, because representing the population is not the goal of nonprobability samples. That said, the fact that nonprobability samples do not represent a larger population does not mean that they are drawn arbitrarily or without any specific purpose in mind. We typically use nonprobability samples in research projects that are qualitative in nature. We will examine several types of nonprobability samples. These include purposive samples, snowball samples, quota samples, and convenience samples.

Convenience or availability

Convenience sampling, also known as availability sampling, is a nonprobability sampling strategy that is employed by both qualitative and quantitative researchers. To draw a convenience sample, we would simply collect data from those people or other relevant elements to which we have the most convenient access. While convenience samples offer one major benefit—convenience—we should be cautious about generalizing from research that relies on convenience samples because we have no confidence that the sample is representative of a broader population. If you are a student who needs to conduct a research project at your school and you decide to conduct a focus group with the staff there, you are using a convenience sampling approach – you are recruiting participants that are easily accessible to you. In addition, if you elect to analyze existing data that your Masters program has collected as part of their graduation exit surveys, you are using data that you readily have access to for your project; again, you have a convenience sample. The vast majority of students I work with on their proposal design rely on convenience data due to time constraints and limited resources.

Purposive

To draw a purposive sample, we begin with specific perspectives or purposive criteria in mind that we want to examine. We would then seek out research participants who cover that full range of perspectives. For example, if you are studying mental health supports on your campus, you may want to be sure to include not only students, but mental health practitioners and student affairs administrators as well. You might also select students who currently use mental health supports, those who dropped out of supports, and those who are waiting to receive supports. The “purposive” part of purposive sampling comes from selecting specific participants on purpose because you already know they have certain characteristics—being an administrator, dropping out of mental health supports, for example—that you need in your sample.

Note that these differ from inclusion criteria, which are more general requirements a person must possess to be a part of your sample; to be a potential participant that may or may not be sampled. For example, one of the inclusion criteria for a study of your campus’ mental health supports might be that participants had to have visited the mental health center in the past year. That differs from purposive sampling. In purposive sampling, you know characteristics of individuals and recruit them because of those characteristics. For example, I might recruit Jane because she stopped seeking supports this month, because she has worked at the center for many years, and so forth.

Also, it’s important to recognize that purposive sampling requires you to have prior information about your participants before recruiting them because you need to know their perspectives or experiences before you know whether you want them in your sample. This is a common mistake that many students make. What I often hear is, “I’m using purposive sampling because I’m recruiting people from the school,” or something like that. That’s not purposive sampling. In most instances they really mean they are going to use convenience sampling-taking whoever they can recruit that fit the inclusion criteria (i.e. have taught in the school). Purposive sampling is recruiting specific people because of the various characteristics and perspectives they bring to your sample. Imagine we were creating a focus group. A purposive sample might gather teachers, parents, administrators, staff, and students together so they can talk as a group. Purposive sampling would seek out people that have each of those attributes.

If you are considering using a purposive sampling approach for your research proposal, you will need to determine what your purposive criteria involves. There are a range of different purposive strategies that might be employed, including: maximum variation, typical case, extreme case, or political case, and you want to be thoughtful in thinking about which one(s) you select and why.

| Purposive Strategy | Description | Student Example |

| Maximum Variation | Case(s) selected to represent a range of very different perspectives on a topic | You interview student leaders from the schools of education, business, the arts, math & science, education, history & anthropology and health studies to ensure that you have the perspective of a variety of disciplines |

| Typical Case | Case(s) selected to reflect a commonly held perspective. | You interview a middle school principal specifically because many of their characteristics fit the statistical profile for leaders in that service area. |

| Extreme Case | Case(s) selected to represent extreme or underrepresented perspectives. | You interview students with an IQ above 140 about their learning experience in high school. |

| Political Case | Case(s) selected to represent a contemporary politicized issue | You analyze media interviews about labour relations with BCTF leaders from 2000 to 2010. |

| Expert Case | Case(s) selected based on specialized content knowledge or expertise | You are interested in studying resilience in students, so you research and reach out to a handful of authorities in this area. |

| Theory-Based Case | Case(s) selected based on their representation of a specific theoretical orientation or some aspect of a given theory | You are interested in studying how training methods vary by practitioner according to their theoretical orientation. You specifically reach out to a teacher trained in Montessori, one conceptualizes their teaching as constructivist, and one who identifies with Self Determination Theory. |

| Critical Case | Case(s) selected based on the likelihood that the case will yield the desired information | You examine a public gaming network forum on social media to see how participants offer support to one another. |

It can be a bit tricky determining how to approach or formulate your purposive cases. Below are a couple additional resources to explore this strategy further.

For more information on purposive sampling consult this webpage from Laerd Statistics on purposive sampling and this webpage from the University of Connecticut on education research.

Snowball

When using snowball sampling, we might know one or two people we’d like to include in our study but then we have to rely on those initial participants to help identify additional participants. Thus, our sample builds and grows as the study continues, much as a snowball builds and becomes larger as it rolls through the snow. Snowball sampling is an especially useful strategy when you wish to study a stigmatized group or behavior. These groups may have limited visibility and accessibility for a variety of reasons, including safety.

Malebranche and colleagues (2010)[5] were interested in studying sexual health behaviors of Black, bisexual men. Anticipating that this may be a challenging group to recruit, they utilized a snowball sampling approach. They recruited initial contacts through activities such as advertising on websites and distributing fliers strategically (e.g. barbershops, nightclubs). These initial recruits were compensated with $50 and received study information sheets and five contact cards to distribute to people in their social network that fit the study criteria. Eventually the research team was able to recruit a sample of 38 men who fit the study criteria.

Snowball sampling may present some ethical quandaries for us and can be difficult to get approval for. Since we are essentially relying on others to help advertise for us, we are giving up some of our control over the process of recruitment. We may be worried about coercion, or having people put undue pressure to have others’ they know participate in your study. To help mitigate this, we would want to make sure that any participant we recruit understands that participation is completely voluntary and if they tell others about the studies, they should also make them aware that it is voluntary, too. In addition to coercion, we also want to make sure that people’s privacy is not violated when we take this approach. For this reason, it is good practice when using a snowball approach to provide people with our contact information as the researchers and ask that they get in touch with us, rather than the other way around. This may also help to protect against potential feelings of exploitation or feeling taken advantage of. Because we often turn to snowball sampling when our population is difficult to reach or engage, we need to be especially sensitive to why this is. It is often because they have been exploited in the past and participating in research may feel like an extension of this. To address this, we need to have a very clear and transparent informed consent process and to also think about how we can use or research to benefit the people we work in the most meaningful and tangible ways.

Quota

Quota sampling is another nonprobability sampling strategy. This type of sampling is actually employed by both qualitative and quantitative researchers, but because it is a nonprobability method, we’ll discuss it in this section. When conducting quota sampling, we identify categories that are important to our study and for which there is likely to be some variation. Subgroups are created based on each category and the researcher decides how many people (or whatever element happens to be the focus of the research) to include from each subgroup and collects data from that number for each subgroup. To demonstrate, perhaps we are interested in studying English as a foreign language learners. We decide that we want to examine equal numbers (seven each) of children placed in an English immersion class, a hybrid class where content is taught in the students native language, native language classes with English language learning happening outside of the classroom. We expect that the experiences and needs across these settings may differ significantly, so we want to have good representation of each one, thus setting a quota of seven for each type of placement.

| Sampling Type | Brief Description |

| Convenience/ Availability | You gather data from whatever cases/people/documents happen to be convenient |

| Purposive | You seek out elements that meet specific criteria, representing different perspectives |

| Snowball | You rely on participant referrals to recruit new participants |

| Quota | You select a designated number of cases from specified subgroups |

As you continue to plan for your proposal, below you will find some of the strengths and challenges presented by each of these types of sampling.

| Sampling Type | Strengths | Challenges |

| Convenience/ Availability | Allows us to draw sample from participants who are most readily available/accessible | Sample may be biased and may represent limited or skewed diversity in characteristics of participants |

| Purposive | Ensures that specific expertise, positions, or experiences are represented in sample participants | It may be challenging to define purposive criteria or to locate cases that represent these criteria; restricts our potential sampling pool |

| Snowball | Accesses participant social network and community knowledge

Can be helpful in gaining access to difficult to reach populations |

May be hard to locate initial small group of participants, concerns over privacy—people might not want to share contacts, process may be slow or drawn-out |

| Quota | Helps to ensure specific characteristics are represented and defines quantity of each | Can be challenging to fill quotas, especially for subgroups that might be more difficult to locate or reluctant to participate |

Wait a minute, we need a plan!

Both qualitative and quantitative research should be planful and systematic. We’ve actually covered a lot of ground already and before we get any further, we need to start thinking about what the plan for your qualitative research proposal will look like. This means that as you develop your research proposal, you need to consider what you will be doing each step of the way: how you will find data, how you will capture it, how you will organize it, and how you will store it. If you have multiple types of data, you need to have a plan in place for each type. The plan that you develop is your data collection protocol. If you have a team of researchers (or are part of a research team), the data collection protocol is an important communication tool, making sure that everyone is clear what is going on as the research proceeds. This plan is important to help keep you and others involved in your research consistent and accountable. Throughout this chapter and the next (Chapter 18—qualitative data gathering) we will walk through points you will want to include in your data collection protocol. While I’ve spent a fair amount of time talking about the importance of having a plan here, qualitative design often does embrace some degree of flexibility. This flexibility is related to the concept of emergent design that we find in qualitative studies. Emergent design is the idea that some decisions in our design will be dynamic and fluid as our understanding of the research question evolves. The more we learn about the topic, the more we want to understand it thoroughly.

Exercises

A research protocol is a document that not only defines your research project and its aims, but also comprehensively plans how you will carry it out. If this sounds like the function of a research proposal, you are right, they are similar. What differentiates a protocol from a proposal is the level of detail. A proposal is more conceptual; a protocol is more practical (right down to the dollars and cents!). A protocol offers explicit instructions for you and your research team, any funders that may be involved in your research, and any oversight bodies that might be responsible for overseeing your study. Not every study requires a research protocol, but what I’m suggesting here is that you consider constructing at least a limited one to help though the decisions you will need to make to construct your qualitative study.

Al-Jundi and Sakka (2016)[6] provide the following elements for a research protocol:

- What is the question? (Hypothesis) What is to be investigated?

- Why is the study important (Significance)

- Where and when will it take place?

- What is the methodology? (Procedures and methods to be used).

- How are you going to implement it? (Research design)

- What is the proposed time table and budget?

- What are the resources required (technical, scientific, and financial)?

While your research proposal in its entirety will focus on many of these areas, our attention for developing your qualitative research protocol will hone in on the two highlighted above. As we go through these next couple chapters, there will be a number of exercises that walk you though decision points that will form your qualitative research protocol.

To begin developing your qualitative research protocol:

- Select the question you have decided is the best to frame your research proposal.

- Write a brief paragraph about the aim of your study, ending it with the research question you have selected.

Here are a few additional resources on developing a research protocol:

Cameli et al., (2018) How to write a research protocol: Tips and tricks.

Ohio State University, Institutional Review Board (n.d.). Research protocol.

World Health Organization (n.d.). Recommended format for a research protocol.

Exercises

Decision Point: What types of data will you be using?

- After having considered the different types of data that have been reviewed here, what type(s) are you planning on using?

- Why is this a good choice, given your research question?

- Are you thinking about using more than one type?

- If so, provide support for this decision.

Exercises

Decision Point: Which non-probability sampling strategy will you employ?

- Thinking about the four non-probability sampling strategies we reviewed, which one makes the most sense for your proposal?

- Why is this is a good fit?

- What challenges or limitations does this present for your study?

- What steps might your take to address these challenges?

Recruiting strategies

Much like quantitative research, recruitment for qualitative studies can take many different approaches. When considering how to draw your qualitative sample, it may be helpful to first consider which of these three general strategies will best fit your research question and general study design: public, targeted, or membership-based. While all will lead to a sample, the process for getting you there will look very different, depending on the strategy you select.

Public

Taking a public approach to recruitment offers you access to the broadest swath of potential participants. With this approach, you are taking advantage of public spaces in an attempt to gain the attention of the general population of people that frequent that space so that they can learn about your study. These spaces can be in-person (e.g. libraries, coffee shops, grocery stores, schools, parks) or virtual (e.g. open chat forums, e-bulletin boards, news feeds). Furthermore, a public approach can be static (such as hanging a flier), or dynamic (such as talking to people and directly making requests to participate). While a public approach may offer broad coverage in that it attempts to appeal to an array of people, it may be perceived as impersonal or easily able to be overlooked, due to the potential presence of other announcements that may be featured in public spaces. Public recruitment is most likely to be associated with convenience or quota sampling and is unlikely to be used with purposive or snowball sampling, where we would need some advance knowledge of people and the characteristics they possess.

Targeted

As an alternative, you may elect to take a targeted approach to recruitment. By targeting a select group, you are restricting your sampling frame to those individuals or groups who are potentially most well-suited to answer your research question. Additionally, you may be targeting specific people to help craft a diverse sample, particularly with respect to personal characteristics and/or opinions.

You can target your recruitment through the use of different strategies. First, you might consider the use of knowledgeable and well-connected community members. These are people who may possess a good amount of social capital in their community, which can aid in recruitment efforts. If you are considering the use of community members in this role, make sure to be thoughtful in your approach, as you are essentially asking them to share some of their social capital with you. This means learning about the community or group, approaching community members with a sense of humility, and making sure to demonstrate transparency and authenticity in your interactions. These community members may also be champions for the topic you are researching. A champion is someone who helps to draw the interest of a particular group of people. The champion often comes from within the group itself. As an example, let’s say you’re interested in studying the experiences of students struggling with attendance. To aid in your recruitment for this study, you enlist the help of a counsellor in your school who does a lot of work at risk youth across the student body.

A targeted approach can certainly help ensure that we are talking to people who are knowledgeable about the topic we are interested in, however, we still need to be aware of the potential for bias. If we target our recruitment based on connection to a particular person, event, or passion for the topic, these folks may share information with us that they think is viewed as favourable or that disproportionately reflects a particular perspective. This phenomenon is due to the fact that we often spend time with people who are like-minded or share many of our views. A targeted approach may be helpful for any type of non-probability sampling, but can be especially useful for purposive, quota, or snowball sampling, where we are trying to access people or groups of people with specific characteristics or expertise.

Membership-based

Finally, you might consider a membership-based approach. This approach is really a form of targeted recruitment, but may benefit from some individual attention. When using a membership-based approach, your sampling frame is the membership list of a particular organization or group. As you might have guessed, this organization or group must be well-suited for helping to answer your research question. You will need permission to access membership, and the identity of the person authorized to grant permission will depend on the organizational structure. When contacting members regarding recruitment, you may consider using directories, newsletters, listservs or membership meetings. When utilizing a membership-based approach, we often know that members possess specific inclusion criteria we need, however, because they are all associated with that particular group or organization, they may be homogenous or like-minded in other ways. This may limit the diversity in our sample and is something to be mindful of when interpreting our findings. Membership-based recruiting can be helpful when we have a membership group that fulfills our inclusion criteria. For instance, if you want to conduct research with teachers, you might attempt to recruit through your school district or the BCTF. In either case, you may find the organization reticent to give you access to their members, and substantial relationship building may be needed to build trust. Membership-based recruitment may be helpful for any non-probability sampling approach, given that the membership criteria and study inclusion criteria are a close fit. Table 17.5 offers some additional considerations for each of these strategies with examples to help demonstrate sources that might correspond with them.

| Recruitment Strategy | Strengths/Challenges | Example of Source for Recruitment |

| Public | Strengths: Easier to gain access; Exposure to large numbers of people

Challenges: Can be impersonal, Difficult to cultivate interest |

Advertising in public events & spaces

Accessing materials in local libraries or museums Finding public web-based resources and sources of data (websites, blogs, open forums)

|

| Targeted | Strengths: Prior knowledge of potential audience, More focused use of resources

Challenges: May be hard to locate/access target group(s), Groups may be suspicious of/or resistant to being targeted |

Working with advocacy group for issue you are studying to aid recruitment

Contacting local expert (historian) to help you locate relevant documents Advertising in places that your population may frequent

|

| Membership-Based | Strengths: Shared interest (through common membership), Potentially existing infrastructure for outreach

Challenges: Organization may be highly sensitive to protecting members, Members may be similar in perspectives and limit diversity of ideas |

Membership newsletters

Listserv or Facebook groups Advertising at membership meetings or events |

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research predominately relies on non-probability sampling techniques. There are a number of these techniques to choose from (convenience/availability, purposive, snowball, quota), each with advantages and limitations to consider. As we consider these, we need to reflect on both our research question and the resources we have available to us in developing a sampling strategy.

- As we consider where and how we will recruit our sample, there are a range of general approaches, including public, targeted, and membership-based.

Exercises

Decision Point: How will you recruit or gain access to your sample?

- Now you’ve decided your data type and sampling strategy…

17.5 What should my sample look like?

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain key factors that influence the makeup of a qualitative sample

- Develop and critique a sampling strategy to support their qualitative proposal

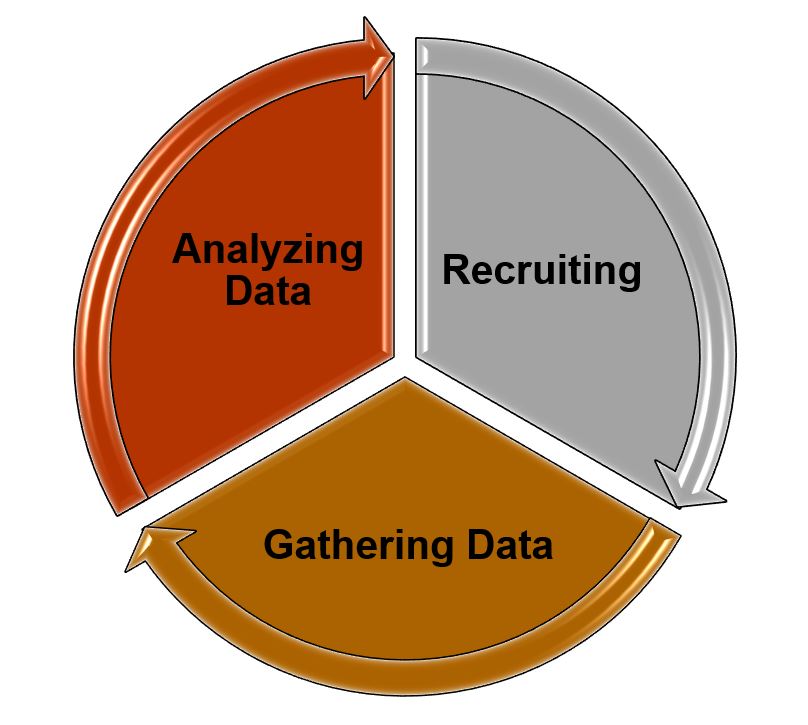

Once you have started your recruitment, you also need to know when to stop. Knowing when to stop recruiting for a qualitative research study generally involves a dynamic and reflective process. This means that you will actively be involved in a process of recruiting, collecting data, beginning to review your preliminary data, and conducting more recruitment to gather more data. You will continue this process until you have gathered enough data and included sufficient perspectives to answer your research question in rich and meaningful way.

The sample size of qualitative studies can vary significantly. For instance, case studies may involve only one participant or event, while some studies may involve hundreds of interviews or even thousands of documents. Generally speaking, when compared to quantitative research, qualitative studies have a considerably smaller sample. Your decision regarding sample size should be guided by a few considerations, described below.

Amount of data

When gathering quantitative data, the amount of data we are gathering is often specified at the start (e.g. a fixed number of questions on a survey or a set number of indicators on a tracking form). However, when gathering qualitative data, we are often asking people to expand on and explore their thoughts and reactions to certain things. This can produce A LOT of data. If you have ever had to transcribe an interview (type out the conversation while listening to an audio recorded interview), you quickly learn that a 15-minute discussion turns into many pages of dialogue. As such, each interview or focus group you conduct represents multi-page transcripts, all of which becomes your data. If you are conducting interviews or focus groups, you will know you have collected enough data from each interaction when you have covered all your questions and allowed the participant(s) to share any and all ideas they have related to the topic. If you are using observational data, you need to spend sufficient time making observations and capturing data to offer a genuine and holistic representation of the thing you are observing (at least to the best of your ability). When using documents and other sources of media, again, you want to ensure that diverse perspectives are represented through your artifact choices so that your data reflects a well-rounded representation of the issue you are studying. For any of these data sources, this involves a judgment call on the researcher’s part. Your judgment should be informed by what you have read in the existing literature and consultation with your professor. Across your data gathering, you will know you have collected enough data from your sample when you begin to hear (or see) the same data over and over. This is called saturation (see discussion below).

As part of your analysis, you will likely eventually break these larger hunks of data apart into words or small phrases, giving you potentially thousands of pieces of data. If you are relying on documents or other artifacts, the amount of data contained in each of these pieces is determined in advance, as they already exist. However, you will need to determine how many to include. With interviews, focus groups, or other forms of data generation (e.g. taking pictures for a photovoice project), we don’t necessarily know how much data will be generated with each encounter, as it will depend on the questions that are asked, the information that is shared, and how well we capture it.

Diversity of perspectives

As you consider your research question, you also may want to think about the potential variation in how your study population might view this topic. If you are conducting a case study of one person, this obviously isn’t a concern, but if you are interested in exploring a range of experiences, you want to plan to intentionally recruit so this level of diversity is reflected in your sample. The level of variation you seek will have direct implications for how big your sample might be. In the example provided above in the section on quota sampling, we wanted to ensure we had equal representation across a host of placements for EFL students. This helped us define our target sample size: (3) settings a quota of (7) participants from each type of setting = a target sample size of (21).

In Chapter 18, we will be talking about different approaches to data gathering, which may help to dictate the range of perspectives you want to represent. For instance, if you conduct a focus group, you want all of your participants to have some experience with the thing that you are studying, but you hope that their perspectives differ from one another. Furthermore, you may want to avoid groups of participants who know each other well in the same focus group (if possible), as this may lead to groupthink or level of familiarity that doesn’t really encourage differences being expressed. Ideally, we want to encourage a discussion where a variety of ideas are shared, offering a more complete understanding of how the topic is experienced. This is true in all forms of qualitative data, in that your findings are likely to be more well-rounded and offer a broader understanding fo the issue if you recruit a sample with diverse perspectives.

Saturation

Finally, the concept of saturation has important implications for both qualitative sample size and data analysis. To understand the idea of saturation, it is first important to understand that unlike most quantitative research, with qualitative research we often at least begin the process of data analysis while we are still actively collecting data. This is called an iterative approach to data analysis. So, if you are a qualitative researcher conducting interviews, you may be aiming to complete 20 interviews. After you have completed your first five interviews, you may begin reviewing and coding (a term that refers to labeling the different ideas found in your transcripts) these interviews while you are still conducting more interviews. You go on to review each new interview that you conduct and code it for the ideas that are reflected there. Eventually, you will reach a point where conducting more interviews isn’t producing any new ideas, and this is the point of saturation. Reaching saturation is an indication that we can stop data collection. This may come before or after you hit 20, but as you can see, it is driven by the presence of new ideas or concepts in your interviews, not a specific number.

This chapter represents our transition in the text to a focus on qualitative methods in research. Throughout this chapter we have explored a number of topics including various types of qualitative data, approaches to qualitative sampling, and some considerations for recruitment and sample composition. It bears repeating that your plan for sampling should be driven by a number of things: your research question, what is feasible for you, especially as a student researcher, best practices in qualitative research. Finally, in subsequent chapters, we will continue the discussion about reflexivity as it relates to the qualitative research process that we began here.

Key Takeaways

- The composition of our qualitative sample comes with some important decisions to consider, including how large should our sample be and what level and type of diversity it should reflect. These decisions are guided by the purposes or aims of our study, as well as access to resources and our population.

- The concept of saturation is important for qualitative research. It helps us to determine when we have sufficiently collected a range of perspectives on the topic we are studying.

Exercises

Decision Point(s): What should your sample look like (sample composition)?

- How will you determine you have gathered enough data?

- Will you start in advance with a set a number of data sources (people or artifacts)?

- If so, how many?

- How was this number determined?

- OR will you use the concept of saturation to determine when to stop?

- Will you start in advance with a set a number of data sources (people or artifacts)?

- How diverse should your sample be and in what ways?

- What supports your decision in regards to the previous question?

Exercises

This isn’t so much a decision point, but a chance for you to reflect on the choices you’ve made thus far in your protocol with regards to your: (1) ethical responsibility, (2) commitment to cultural humility, and (3) respect for empowerment of individuals and groups as an education researcher. Think about each of the decisions you’ve made thus far and work across this grid to identify any important considerations that you need to take into account.

| Decision Point | Ethical Responsibility | Cultural Humility | Empowerment |

| Research Question | |||

| Type of Data | |||

| Sampling Approach | |||

| Recruitment/ Access | |||

| Sample Composition |

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

You have been prompted to make a number of choices regarding how you will proceed with gathering your qualitative sample. Based on what you have learned and what you are planning, respond to the following questions below.

- What are the strengths of your sampling plan in respect to being able to answer your qualitative research question?

- How feasible is it for you, as a student researcher, to be able to carry out your sampling plan?

- What reservations or questions do you still need to have answered to adequately plan for your sample?

- What excites you about your proposal thus far?

- What worries you about your proposal thus far?

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html ↵

- Patel, J., Tinker, A., & Corna, L. (2018). Younger workers’ attitudes and perceptions towards older colleagues. Working with Older People, 22(3), 129-138. ↵

- Veenstra, A. S., Iyer, N., Hossain, M. D., & Park, J. (2014). Time, place, technology: Twitter as an information source in the Wisconsin labor protests. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 65-72. ↵

- Ohmer, M. L., & Owens, J. (2013). Using photovoice to empower youth and adults to prevent crime. Journal of Community Practice, 21(4), 410-433. ↵

- Malebranche, D. J., Arriola, K. J., Jenkins, T. R., Dauria, E., & Patel, S. N. (2010). Exploring the “bisexual bridge”: A qualitative study of risk behavior and disclosure of same-sex behavior among Black bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health, 100(1), 159-164. ↵

- Al-Jundi, A., & SakkA, S. (2016). Protocol writing in clinical research. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 10(11), ZE10. ↵

Research that involves the use of data that represents human expression through words, pictures, movies, performance and other artifacts.

One of the three ethical principles in the Belmont Report. States that benefits and burdens of research should be distributed fairly.

Case studies are a type of qualitative research design that focus on a defined case and gathers data to provide a very rich, full understanding of that case. It usually involves gathering data from multiple different sources to get a well-rounded case description.

the various aspects or dimensions that come together in forming our identity

The unintended influence that the researcher may have on the research process.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study

Rigor is the process through which we demonstrate, to the best of our ability, that our research is empirically sound and reflects a scientific approach to knowledge building.

A form of data gathering where researchers ask individual participants to respond to a series of (mostly open-ended) questions.

A form of data gathering where researchers ask a group of participants to respond to a series of (mostly open-ended) questions.

Observation is a tool for data gathering where researchers rely on their own senses (e.g. sight, sound) to gather information on a topic.

Triangulation of data refers to the use of multiple types, measures or sources of data in a research project to increase the confidence that we have in our findings.

sampling approaches for which a person’s likelihood of being selected for membership in the sample is unknown

A convenience sample is formed by collecting data from those people or other relevant elements to which we have the most convenient access. Essentially, we take who we can get.

A quota sample involves the researcher identifying a subgroups within a population that they want to make sure to include in their sample, and then identifies a quota or target number to recruit that represent each of these subgroups.

For a snowball sample, a few initial participants are recruited and then we rely on those initial (and successive) participants to help identify additional people to recruit. We thus rely on participants connects and knowledge of the population to aid our recruitment.

In a purposive sample, participants are intentionally or hand-selected because of their specific expertise or experience.

Content is the substance of the artifact (e.g. the words, picture, scene). It is what can actually be observed.

Context is the circumstances surrounding an artifact, event, or experience.