2 Musculoskeletal System

Learning Objectives

- Identify the anatomy of a long bone at the macroscopic and microscopic levels.

- Identify the bones of the axial skeleton.

- Identify the bones of the appendicular skeleton.

- Define the terms agonist and antagonist muscles and provide examples of such muscle pairs.

- Identify types of joint movements.

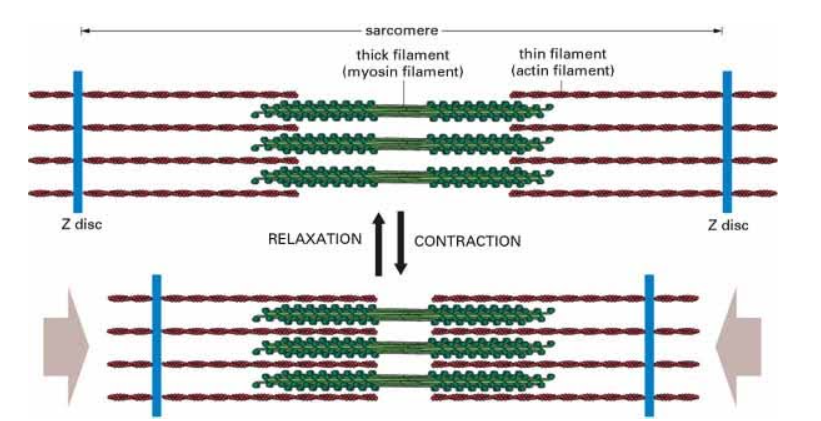

- Describe the sliding filament model of skeletal muscle contraction.

- Conduct an experiment and explain the experimental results of the role of ATP and salt ions (potassium & magnesium) in skeletal muscle contraction.

- Identify selected skeletal muscles.

MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM

The skeletal and muscle systems work together as the musculoskeletal system to enable the body’s support and movement. The skeletal system is made up of about 300 bones at birth that eventually fuse into 206 bones as an adult. Bones are composed of two types of tissue: compact bone and spongy bone. The skeletal system also includes the body’s ligaments, tendons, and cartilage. The muscular system contains three types of muscle tissue: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle. In today’s lab, we will focus on skeletal muscles due to their attachment to bones by tendons to allow for movement.

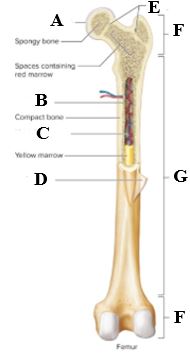

MACROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF A LONG BONE

Bones can be classified based on their shape as long bone, short bone, flat bone, irregular bone, and sesamoid bone (bones embedded in tendons). The general anatomy of a bone is demonstrated by the long bone. Examples of a long bone are the humerus and the femur. A typical long bone has the following parts (Figure 2.1):

- Diaphysis: the long, cylindrical, main portion of the bone (the bone’s shaft). It is made up of compact bone.

- Epiphysis (plural epiphyses): each end of a bone. They are made up of spongy bone.

- Epiphyseal line (or growth plate): lies between the diaphysis and epiphysis, is a layer of hyaline cartilage, and is responsible for bone growth during childhood and adolescence.

- Articular cartilage: thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers the epiphyses where bone meets with bone. It reduces friction and absorbs shock at freely movable joints.

- Periosteum: tough sheath of dense irregular connective tissue that surrounds the bone surface wherever there is no articular cartilage. It contains blood vessels, nerves, and osteoblasts (bone forming cells) that enable the bone to grow in thickness and repair a bone break (fracture). It also serves as an attachment point for ligaments and tendons.

- Medullary cavity: the space within the bone shaft (diaphysis) that contains fatty yellow bone marrow and osteoblasts.

- Endosteum: a thin membrane that lines the medullary cavity and contains osteoblasts.

Figure 2.1 Macroscopic anatomy of a long bone (femur). © McGraw Hill Education

Note to students: Write all data and answers to questions on the Lab Report provided.

Activity 1: Identifying Macroscopic Anatomy of a Long Bone

Label the anatomy of a long bone in Figure 2.1, using the text, by recording your answers on the Lab Report.

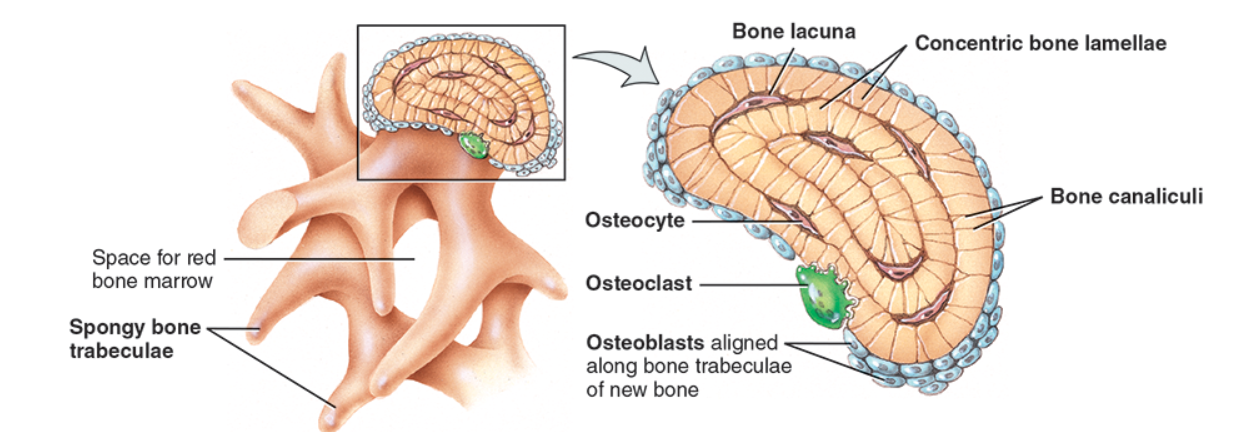

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF A LONG BONE

As stated previously, bone is composed of two types of tissue: compact bone and spongy bone. They differ in density, or how tightly the matrix is packed together. Compact bone makes up the diaphysis of the bone. It provides protection and support based on its cylindrical structural unit, the osteon. The osteon consists of concentric rings of matrix called lamellae that are arranged around the central canal, which contains blood vessels. Between the concentric lamellae are small spaces called lacunae that contain osteocytes, or mature bone cells. Small channels, called canaliculi, connect the lacunae, which allows the processes of the osteocytes to pass nutrients between them in the extracellular fluid. (Figure 2.2)

Figure 2.2 Microscopic anatomy of compact bone.

Spongy bone makes up the interior of the epiphyses, the interior section of the medullary cavity of long bone and the interior bone tissue of short, flat, sesamoid, and irregularly shaped bones. It does not contain osteons like compact bone. It consists of lamellae that are arranged in an irregular pattern of thin columns called trabeculae, which results in spaces where red bone marrow is found. Red bone marrow contains stem cells that produce mature blood cells. The trabeculae consist of lacunae where osteocytes lie. The lacunae are connected by canaliculi. (Figure 2.3)

Figure 2.3 Microscopic anatomy of spongy bone. © John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Activity 2: Understanding the structures of microanatomy of the bone.

Match each term (a – i) with its definition (1 – 9). Record answers on the Lab Report.

|

Term |

Definition |

|

a. Osteocyte |

1. Small spaces between the lamellae that contain osteocytes |

|

b. Spongy bone |

2. The structural unit of bone |

|

c. Canaliculi |

3. Loosely structured bone at the epiphyses and interior of medullary cavity |

|

d. Lamellae |

4. Canal at the center of each osteon that contains blood vessels |

|

e. Osteon |

5. Small channels that connect lacunae to allow nutrients to travel between osteocytes |

|

f. Central canal |

6. Thin columns that are in an irregular pattern that results in spaces |

|

g. Lacunae |

7. Densely structured bone that makes up the diaphysis of the bone |

|

h. Trabeculae |

8. Concentric rings of matrix |

|

i. Compact bone |

9. Mature bone cells |

THE SKELETON

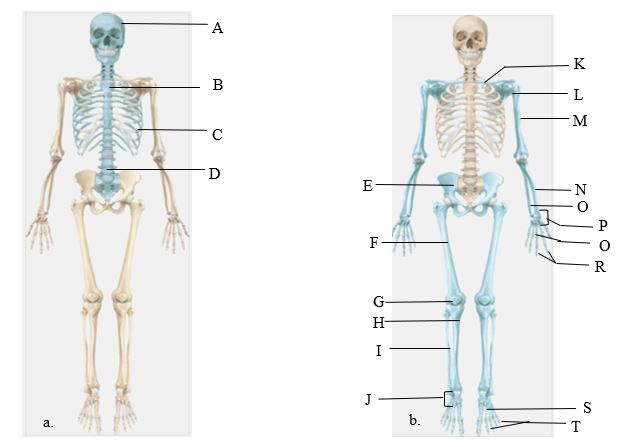

The skeleton is divided into two divisions: axial skeleton and appendicular skeleton. The axial skeleton consists of the 80 bones that lie around the axis of the body, or longitudinal line that runs down the middle, through the body’s center of gravity. It includes the skull, the vertebral column, sternum, and ribs. The appendicular skeleton consists of the other 126 bones that make up the upper and lower appendages, or limbs, and the bones that form the shoulder and hip girdles that connect the appendages to the axial skeleton. (Figure 2.4)

Figure 2.4: (a) bones of the axial skeleton are depicted in blue; (b) bones of the appendicular skeleton are depicted in blue. © John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

| Word Bank for Activities 3 & 4 | Scapula | |

| Carpals | Metacarpals | Skull |

| Clavicle | Metatarsals | Sternum |

| Femur | Patella | Tarsals |

| Fibula | Phalanges | Tibia |

| Hip bone (coxal bone) | Radius | Ulna |

| Humerus | Ribs | Vertebral Column |

Activity 3: Identify the bones of the axial skeleton

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the bones of the axial skeleton in Figure 2.4a. Record answers on the Lab Report.

Activity 4: Identify the bones of the appendicular skeleton

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the bones of the appendicular skeleton in Figure 2.4b. Record answers on the Lab Report.

AXIAL SKELETON

SKULL

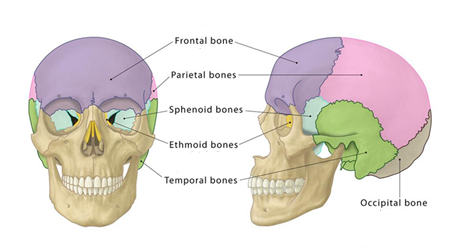

The bones of the skull are divided into two types: cranial bones and facial bones. There are 8 cranial bones that form the brain cavity: frontal bone, 2 parietal bones, 2 temporal bones, occipital bone, sphenoid bone, and ethmoid bone. When viewing the skull from the inferior, or underside, the foramen magnum can be found in the occipital bone. The foramen magnum is a large hole through which the spinal cord passes to reach the brain cavity and connect with the brain. There are 14 facial bones that form the anterior section of the skull, or face: 2 nasal bones, 2 maxillae, 2 zygomatic bones, the mandible, 2 lacrimal bones, 2 palatine bones, 2 inferior nasal concha, and the vomer. (Figure 2.5)

a. b.

b.

Figure 2.5: (a) the colored bones are the cranial bones; (b) the colored bones are the facial bones; (c) inferior view of the skull

Figure 2.5: (a) the colored bones are the cranial bones; (b) the colored bones are the facial bones; (c) inferior view of the skull

Activity 5: Identify the bones of the skull

While examining a skull model, match the skull bone (a – j) with its location (1 – 10). Record your answers on the Lab Report.

|

Skull Bone |

Location |

|

a. Frontal bone |

1. Located on the sides of skull |

|

b. Occipital bone |

2. Located at the back of the skull; form base of skull |

|

c. Mandible |

3. Lower jaw |

|

d. Sphenoid bone |

4. Forms bridge of nose |

|

e. Palatine bone |

5. Forms forehead |

|

f. Temporal bone |

6. Forms cheekbones |

|

g. Maxilla |

7. Forms base & side of skull, as well part of the eye orbits |

|

h. Zygomatic bone |

8. Forms upper jaw |

|

i. Parietal bone |

9. Forms the floor of the nasal cavity & hard palate |

|

j. Nasal bone |

10. Forms top & sides of the skull |

VEREBRAL COLUMN

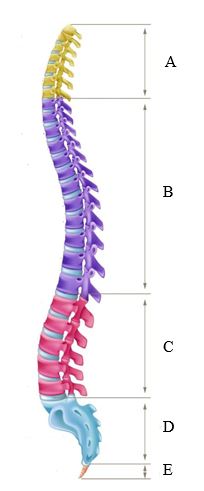

The vertebral column, also called the spine or backbone, is comprised of 33 vertebrae that surround and protect the spinal cord. These are distributed as follows (Figure 2.6):

- Cervical vertebrae (7): form the neck region

- Thoracic vertebrae (12): articulate with the 12 ribs of the chest

- Lumbar vertebrae (5): support the lower back

- Sacrum (5 fused): triangular bone at the base of the spine

- Coccyx (4 fused): form the tailbone

Figure 2.6: Vertebral column

Activity 6: Identify the location of the vertebrae in the spine.

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the type of vertebrae of the vertebral column (spine) in Figure 2.6. Record answers on the Lab Report.

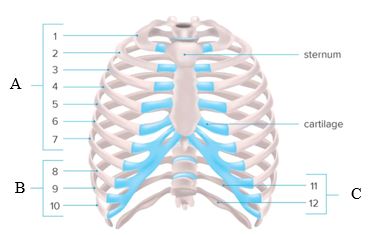

RIB CAGE

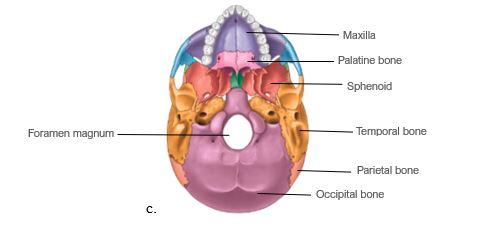

The rib cage is made up of 12 pairs of ribs that are categorized based on how they are attached in the anterior. The first 7 ribs are true ribs due to attaching directly to the sternum by costal cartilage. The next three ribs (ribs 8-10) are false ribs as they connect to the costal cartilage of rib 7 that then attaches indirectly to the sternum. Ribs 11 and 12 are floating ribs due to not attaching to the sternum at all. In the posterior, the 12 ribs attach to the thoracic vertebrae The rib cage protects vital organs in the chest cavity, which are the heart, lungs, and diaphragm. Working with associated muscles, the rib cage expands and contracts during breathing to allow space for the lungs to inflate and deflate. (Figure 2.7)

Figure 2.7: Rib cage. Costal cartilage depicted in blue.

Activity 7: Identifying types of ribs

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the types of ribs illustrated in Figure 2.7. Record answers on the Lab Report.

APPENDICULAR SKELETON

UPPER LIMB

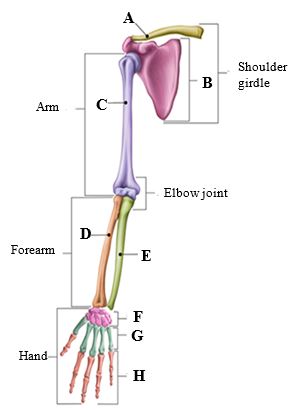

The upper limb refers to the bones of the shoulder girdle, arm, forearm, and hand. The specific bones that are part of the upper limb are the following (Figure 2.8):

1. Clavicle: collar bone

2. Scapula: shoulder blade

3. Humerus: long bone of upper arm

4. Radius: lateral bone of forearm

5. Ulna: medial bone of forearm

6. Carpals: wrist bones (8 in each wrist)

7. Metacarpals: bones of the palm (5 in each palm)

8. Phalanges: bones of fingers (14 in each hand)

Activity 8: Identify the bones of the upper limb.

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the bones of the upper limb in Figure 2.8. Record answers on the Lab Report.

Figure 2.8: Bones of the upper limb

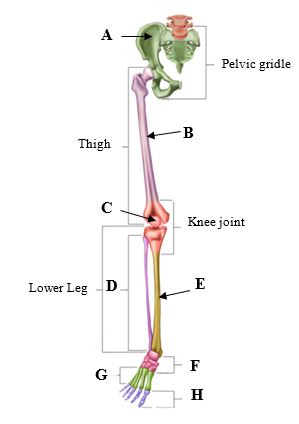

LOWER LIMB

The lower limb refers to the bones of the pelvic girdle, thigh, lower leg, and foot. The specific bones that are part of the lower limb are the following (Figure 2.9):

1. Coxal bone: hip bone

2. Femur: thigh bone

3. Patella: kneecap

4. Fibula: lateral smaller bone of lower leg

5. Tibia: medial larger bone of lower leg

6. Tarsals: ankle bones (7 in each ankle)

7. Metatarsals: bones of the forefoot (5 in each foot)

8. Phalanges: bones of toes (14 in each foot)

Figure 2.9: Bones of the lower limb

Activity 9: Identify the bones of the lower limb.

Examine a model of the skeleton and use the text to label the bones of the lower limb in Figure 2.9. Record answers on the Lab Report.

JOINTS

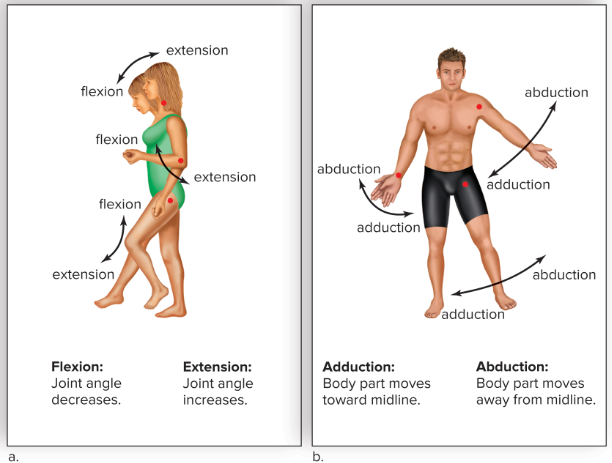

Joints are where two or more bones articulate, or connect, to enable movement and provide stability to the body by working with the muscular system. There are various types of joint movements. Figure 2.10 demonstrates a few examples:

Flexion: decreasing angle between two body parts

Extension: increasing angle between two body parts

Adduction: movement of a body part towards the midline of the body

Abduction: movement of a body part away from the midline of the body

Rotation: movement of a body part around its own axis

Circumduction: circular movement of a limb

Inversion: turning the sole of the foot inward

Eversion: turning the sole of the foot outward

Figure 2.10: Joint movements. (a) Flexion vs. extension; (b) Adduction vs. abduction; (c) Rotation vs. circumduction; (d) Inversion vs. eversion. © McGraw Hill Education

MUSCULAR SYSTEM

As stated previously, the muscular system is made up of 3 types of muscles: cardiac muscle, smooth muscle, and skeletal muscle. Today’s lab will focus on skeletal muscles since those are the muscles that work with the skeletal system for the body’s movements.

In order for skeletal muscles to cause movement, they have to contract. Muscles shorten as they contract, and therefore only pull on the bone they are attached to via tendons. Since muscles cannot push, muscles work together in antagonistic pairs where one muscle contracts (the agonist) to cause a movement while the other muscle (the antagonist) relaxes or lengthens to allow that movement. For example, elbow flexion is driven by the biceps brachii of the upper arm where it contracts while the triceps brachii relaxes.

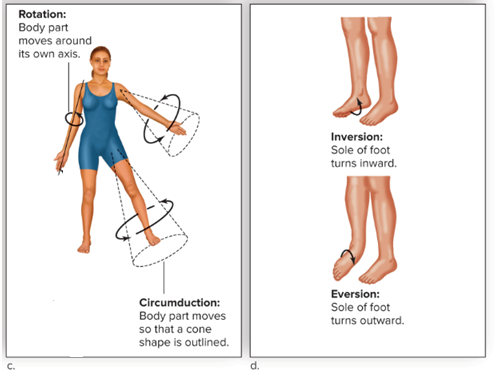

SKELETAL MUSCLE STRUCTURE

Skeletal muscles vary considerably in size, shape, and arrangement of fibers. Skeletal muscles are highly organized in groups of fascicles wrapped in connective tissue. Within each fascicle, there are bundles of muscle fibers wrapped in connective tissue. Each muscle fiber contains one muscle cell, or myocyte, which is composed of bundles of myofibrils. A myofibril is made up of the myofilament proteins actin and myosin that form the repeating units called sarcomeres. The sarcomere is the functional unit that is responsible for muscle contraction. (Figure 2.11). Under the microscope, skeletal muscle appears to have fine stripes, called striations. That pattern is due to the highly organized actin and myosin proteins. Actin is a thin myofilament, which appears lighter in color microscopically, whereas myosin is a thick myofilament, which appears darker in color. The alternating actin and myosin proteins create the illusion of stripes, the striations.

Figure 2.11: Structure of skeletal muscle.

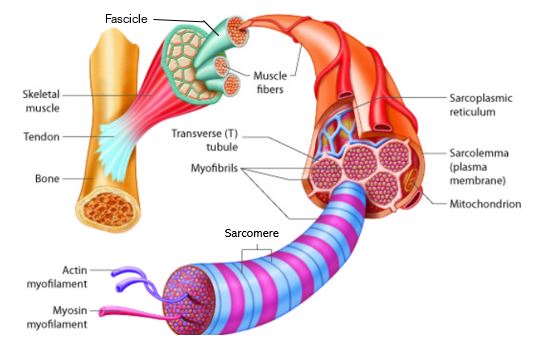

SKELETAL MUSCLE CONTRACTION

For muscle contraction to occur, an electrical stimulus from the nervous system travels down to the muscle fiber, triggering the release of calcium. The calcium ions bind to troponin exposing myosin binding sites on actin filaments. Once myosin heads bind to the actin filament, cross-bridges are formed, and myosin can carry out a power stroke, pulling the actin filaments, thereby shortening the sarcomere. (Figure 2.12). This power stroke is powered by the breakdown of ATP. After the power stroke, ATP binds to the myosin head, causing myosin to detach from actin. These steps result in the shortening of the muscle fiber, which is said to have contracted.

Figure 2.12: Sliding Filament Model of Muscle Contraction

In today’s lab, we will be working with glycerinated rabbit muscle to demonstrate the sliding filament model of muscle contraction. Glycerinated muscle is different from muscle in living tissue described above. The glycerination process removes ions and ATP from the tissue and disrupts troponin/myosin complex so that the binding sites on actin filaments are no longer blocked. Due to this chemical change, calcium is not needed to induce muscle contraction. However, when no ATP is present the myosin heads are not activated. ATP is still required as the source of energy for contraction. Myosin requires the cofactors magnesium (Mg2+) and potassium (K+) to break down ATP and enhance the strength of muscle contraction.

Activity 10: Contraction of Glycerinated Rabbit Muscle

Preparation carried out by the lab instructor: One test tube of skeletal muscle tissue per lab section

- Remove the skeletal muscle strip, which is tied to a stick, from its test tube. One strip contains hundreds of muscle fibers.

- Pour the glycerol from the test tube into a petri plate.

- Cut the muscle strip into pieces that are about 2 cm in length. (Line up a centimeter ruler under the petri plate to estimate the length before cutting.) Drop these pieces into the glycerol in the petri plate. One piece of muscle tissue is sufficient for each group of 2 students or more.

Experimental Procedure carried out by students:

- Using a needle probe, gently tease the muscle segment into very thin strands. You will see optimal results with single muscle fibers, but these are difficult to obtain. The thinnest strand that you will likely get is a group of two to four muscle fibers.

- Label three slides: 1, 2, and 3. Mount three of the thinnest strands onto 3 separate microscope slides in a small amount of glycerol. Do not cover with a coverslip.

Note: The less glycerol used, the easier the muscle fibers are to measure. - Using your microscope, measure the length of each muscle strand with a millimeter ruler. Record these lengths in Table 2.1 on the Lab Report.

- Flood muscle strands on Slide #1 with several drops of solution containing ATP plus KCl and MgCl2. Observe the reaction of the muscle fibers.

- Flood muscle strands on Slide #2 with several drops of solution of ATP alone. Observe the reaction of the muscle fibers.

- Flood muscle strands on Slide #3with several drops of solution of KCl and MgCl2 alone. Observe the reaction of the muscle fibers.

- After 5 minutes or more for each of the experimental conditions, re-measure each of the muscle strands with millimeter ruler, and calculate the degree of contraction by subtracting the final length from the initial length. Record on the Lab Report.

NAMES OF SKELETAL MUSCLES

The names of skeletal muscles are derived from various characteristics:

- Shape: name reflects shape of muscle; Examples: deltoid (triangular), orbicularis (circular)

- Location: name reflects structure near where muscle is found; Examples: brachialis (arm), temporalis (near temporal bone)

- Size: name reflects size in relation to other muscles; Examples: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus

- Action: name reflects movement of the muscle; Examples: adductor brevis (moves bones towards midline), extensor digitorum (extends digits or fingers)

- Number of attachments: number of tendons that attach muscle to bone; Examples: biceps brachii (two attachment points), quadriceps (four attachment points)

- Direction of fibers: direction of muscle fibers relative to body’s midline; Examples: rectus abdominis (parallel to midline), transverse abdominis (perpendicular to midline)

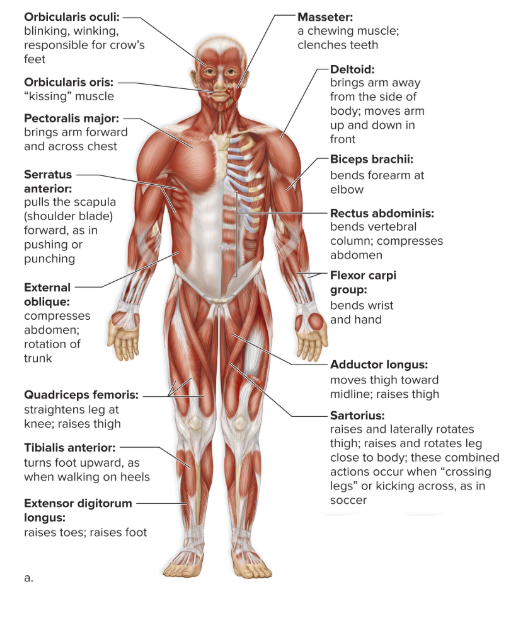

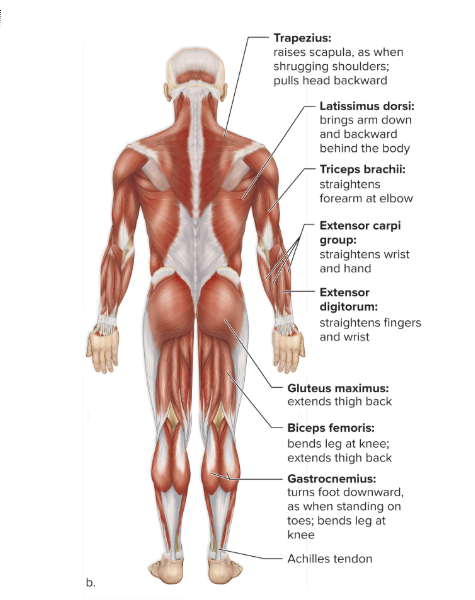

Using Figure 2.13, identify major skeletal muscles of the body and learn what action they carry out.

Figure 2.13: Superficial skeletal muscles of the human body (a) anterior view and (b) posterior view. © McGraw Hill Education

Activity 11: Identify skeletal muscle locations

While examining a model of a muscle man and using Figure 2.13, match location in the body (a – l) with the name of the muscle (1 – 14). (Answers may be used more than once.)

|

Location on the Body |

Name of muscle |

|

a. Face |

1. Gluteus maximus |

|

b. Chest |

2. Gastrocnemius |

|

c. Front of Upper arm |

3. Rectus abdominis |

|

d. Back of Upper arm |

4. Pectoralis major |

|

e. Front of Forearm |

5. Orbicularis oculi |

|

f. Back of Forearm |

6. Trapezius |

|

g. Abdomen |

7. Biceps brachii |

|

h. Front of Thigh |

8. Quadriceps femoris |

|

i. Back of Thigh |

9. Extensor digitorum |

|

j. Front of Lower Leg |

10. Latissimus dorsi |

|

k. Back of Lower Leg |

11. External obliques |

|

l. Back |

12. Tibialis anterior |

|

|

13. Triceps brachii |

|

|

14. Flexor carpi groups |

Activity 12: Lab Review

On the Lab Report, answer the questions in the Lab Review section.

Link to Lab Report: Lab 2 Musculoskeletal System Lab Report

REFERENCES

The A Level Biologist – Your Hub. (2023, March 20). Sliding filament theory | The A Level Biologist – Your Hub. The a Level Biologist – Your Hub |. https://thealevelbiologist.co.uk/sliding-filament-theory/

Allen. (2024, August 12). Vertebral column. https://allen.in/neet/biology/vertebral-column

Carolina Biological. (2025). Contraction of Glycerinated Muscle with ATP. https://www.carolina.com/teacher-resources/Interactive/glycerinated-muscle-activity/tr10760.tr?srsltid=AfmBOooLomoRC4j0kA75tbq8rTiUBOdV81yVvFLe7B_cp4_uJ_4jVzPh

Dresden, D. (2023, June 23). How many ribs does the human body have? Differences between men and women. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/how-many-ribs-do-humans-have#how-many

Fremont Orthopedic & Rehabilitative Medicine. (2020, January 1). What does the upper extremity consist of? | Fremont Orthopedic & Rehabilitative Medicine. https://formortho.com/ufaqs/what-does-the-upper-extremity-consist-of/

Jen. (2017, January 29). Compact Bone Anatomy. Pinterest. https://www.pinterest.com/pin/527554543835696080/

Mader, Sylvia S. (2023). Laboratory Manual for Human Biology. 17th edition. McGraw-Hill.

Nemours Kids Health. (2023). Your bones (for kids). https://kidshealth.org/en/kids/bones.html

Nursing Hero. (2025). Muscular Levels of Organization. https://www.nursinghero.com/study-guides/cuny-csi-ap-1/muscular-levels-of-organization

The Skeletal System.net. (2025). The Skull: Names of Bones in the Head, with Anatomy, & Labeled Diagram. https://www.theskeletalsystem.net/skull-bones

Tortora, Gerard J. and Bryan H. Derrickson. (2016). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, 15th edition. John Wiley and Sons.

Urfingus. (2025). Bones lower limb with name vector image. VectorStock. https://www.vectorstock.com/royalty-free-vector/bones-lower-limb-with-name-vector-28407999

Welsh, Charles and Cynthia Prentice-Craver. (2023). Hole’s Essentials of Human Anatomy and Physiology. 15th edition. McGraw-Hill.